Doctor of Psychology Carlos Rebolleda explains what emotional intelligence in schizophrenia is, its assessment, and the deficits in schizophrenia.

Emotional intelligence in schizophrenia: definition

The four-branch model of emotional intelligence proposed by researchers J.D. Mayer and P. Salovey in 1997 defines it as a type of intelligence different from others, composed of four abilities or “branches” specifically called emotional perception, emotional facilitation, emotional understanding and emotional management which, in turn, are organized into two areas called experiential and strategic.

As Mayer, Salovey and Caruso (2002) indicate, the experiential area refers to the individual’s capacity to perceive, respond to and manipulate emotional information without this necessarily implying comprehension. It indicates the accuracy with which the subject can “read” and express emotions and whether they can compare emotional information with other types of emotional experiences (for example, colors and sounds). This shows how the individual functions under the influence of different emotions. This area is made up of the perception and emotional facilitation branches.

1. Emotional perception

Emotional perception refers to the ability to recognize how an individual feels and those around them. This branch implies the ability to perceive and express feelings, as well as to pay attention to and accurately decode emotional signals from facial expressions, voice tone and artistic expressions (Mayer et al., 2002).

2. Emotional facilitation

Emotional facilitation focuses on how emotions affect cognition and can be used to reason, solve problems or make decisions (Mayer et al., 2002). It is known that some emotions, such as fear, can negatively affect cognition but, as multiple studies have shown, they can also enhance cognitive abilities, for example, by helping the individual prioritize what is most relevant when paying attention or by improving concentration when facing a task.

The so-called strategic area would be the individual’s capacity to understand and manage emotions without necessarily perceiving or experiencing them correctly. It indicates the accuracy with which the person is able to comprehend the meaning of emotions and the skill to handle both their own emotions and those of others. The understanding and emotional management branches make up this area (Mayer et al., 2002).

3. Emotional understanding

As Mayer et al. (2002) point out, the emotional understanding branch refers to the individual’s ability to label emotions, that is, to recognize that there are groups of related terms for them. The ability to understand how different emotions arise, how they combine or change over time, are fundamental components of emotional intelligence, as well as important aspects for relating with other people or improving self-knowledge.

4. Emotional management

Finally, the emotional management branch refers to the individual’s ability to, at appropriate times, not repress their emotions but rather work with them reflectively and use them to make better decisions. A term historically associated with this branch is emotional regulation, which has usually been understood as the repression or rationalization of emotions; however, this term actually refers to the involvement of emotions in thinking, not to their minimization or elimination (Mayer et al., 2002).

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Emotional intelligence in schizophrenia: Assessment

Emotional intelligence is considered an important component of social cognition (Matthews, Zeidner and Roberts, 2007; Mayer and Salovey, 1997) and since the MATRICS committee recommended in 2003 the management branch of the MSCEIT (Mayer et al., 2002) as the sole tool to measure social cognition in schizophrenia, several studies have attempted to explore the psychometric characteristics of the test, especially in populations diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Emotional intelligence in schizophrenia: test

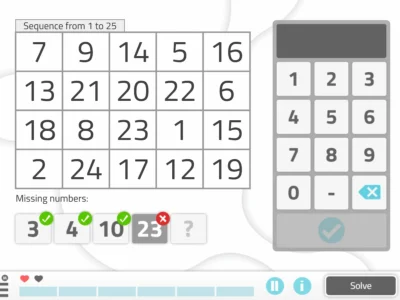

The Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT; Mayer et al., 2002) is based on the four-branch model and, through 141 items divided into eight tasks, yields a total of seven scores: an overall score, two for the experiential and strategic areas, and four for each of the branches that compose the model. The names of these tests are as follows:

- Emotional perception: Composed of the tasks called Drawings and Faces,

- emotional facilitation: Comprised of the subtests Facilitation and Sensations,

- emotional understanding: Composed of Changes and Combinations,

- Emotional management: Comprised of Emotional Management and Emotional Relations.

Reliability was 0.91 for the total score, 0.91 and 0.85 for the experiential and strategic areas respectively, while Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the branches ranged from the lowest, yet adequate, coefficient of 0.74 in emotional facilitation to the highest of 0.89 in the case of emotional perception (Mayer et al., 2002).

Spanish adaptation of the MSCEIT: Extremera and Fernández-Berrocal (2009

Extremera and Fernández-Berrocal (2009) carried out the Spanish adaptation of the MSCEIT which, in turn, shows reliability coefficients very similar to or even higher than those found in the original test, being 0.95 for the total score, 0.93 and 0.90 for the experiential and strategic areas, 0.93 in perception, 0.76 in facilitation, 0.83 in understanding and 0.85 in emotional management. The Spanish adaptation, like other adaptations of the MSCEIT, shows adequate levels of face, predictive and content validity.

Emotional intelligence in schizophrenia: Deficits in schizophrenia

Some studies have found the existence of deficits in emotional intelligence both in patients diagnosed with psychiatric disorders (Lizzeretti, Extremera and Rodríguez, 2012), and in their direct relatives (Sanders and Szymanski, 2012).

Regarding the study of deficits in emotional intelligence in psychosis, one of the first investigations that used this concept as it is currently known was that of Aguirre, Sergi and Levy (2008), who found that people with high levels of schizotypy show deficits in emotional intelligence that, in turn, significantly affect their psychosocial functioning.

However, the study of the emotional deficits that accompany a psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia is much older; for example, the reduction these patients show in facial emotional expression has been confirmed in numerous studies (Andreasen, 1979; Borod et al., 1990; Tremeau et al., 2005; Yecker et al., 1999), a deficit that, as has been shown, is present even several years before the person develops the illness (Hafner et al., 2003; Yung and McGorry, 1996), which makes it a strong candidate to constitute an endophenotypic trait of the disorder.

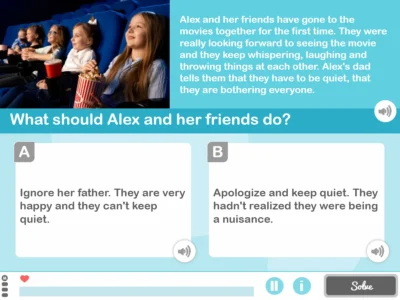

These problems are not limited to facial expression; patients diagnosed with schizophrenia also show difficulties in identifying and verbalizing their own emotions (Cedro, Kokoszka, Popiel and Narkiewicz-Jodko, 2001; Stanghellini and Ricca, 2010; Van’t Wout, Aleman, Bermond and Kahn, 2007; Yu et al., 2011), a deficit known as alexithymia (Sifneos, 1973).

Added to these deficits are the problems these individuals show when recognizing emotional expressions in others, especially when those emotions are negative (Edwards et al., 2002; Kohler et al., 2003; Mandal et al., 1998; Scholten, Aleman, Montagne and Kahn, 2005).

Emotion regulation deficits have also been found in this population (Nuechterlein and Green, 2006), with emotional suppression being the self-regulation strategy these subjects commonly use (Kimhy et al., 2012; Van der Meer, Van’t Wout and Aleman, 2009). While the only emotional area in which patients diagnosed with schizophrenia appear to function similarly to the non-affected population is the capacity to experience emotions (Kring, Barrett and Gard, 2003; Kring and Earnst, 1999).

Even so, the aspect on which there is full agreement today concerns the negative influence these emotional deficits have on the individual’s psychosocial functioning (Baslet, Termini and Herberner, 2009; Kee, Green, Mintz and Brekke, 2003; Kimhy et al., 2012; Kring and Caponigro, 2010).

Research using the MSCEIT as a measure

As for studies that have used the MSCEIT as a measure, for example, Eack et al. (2010) expand on results obtained in three previous studies (Eack et al., 2009; Kee et al., 2009; Nuechterlein et al., 2008), using a sample of 64 individuals diagnosed with various psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia, to whom they applied this test.

Those authors found, first, that the scores obtained by the subjects were significantly lower than those of the non-psychosis population, although they emphasize the need to carry out rigorous studies that can yield more reliable results about the true degree to which these differences occur, since some studies claim that the most affected branch would be emotional management (Wojtalik, Eack and Keshavan, 2013), while others find that it is emotional understanding (Dawson et al., 2012; Kee et al., 2009).

Not all studies at this level find impairment in all branches that make up the test; for example, Kee et al. (2009) do not find significant differences in emotional facilitation between the group of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and the non-diagnosed population. This reinforces the need to continue researching the actual differences and the degree to which they occur.

At the neurostructural level, Wojtalik et al. (2013) found that those patients who exhibit dysfunction in the facilitation, understanding and emotional management branches show a significant reduction of gray matter in both the left parahippocampal gyrus and the right posterior cingulate gyrus.

Bibliography:

- Aguirre, F., Sergi, M. J., and Levy, C. A. (2008). Emotional intelligence and social functioning in person with schizotypy. Schizophrenia Research, 104(1), 255-264.

- Andreasen, N.C. (1979). Affective flattening and the criteria for schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 136(7), 944-947.

- Baslet, G., Termini, L., and Herberner, E. (2009). Deficits in emotional awareness in schizophrenia and their relationships with other measures of functioning. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(9), 655-660.

- Borod, J. C., Welkowitz, J., Alpert, M., Brozgold, A. Z., Martin, C., Peselow, E., and Diller, L. (1990). Parameters of emotional processing in neuropsychiatric disorders: conceptual issues and battery of tests. Journal of Communication Disorders, 23(4), 247-271.

- Cedro, A., Kokoszka, A., Popiel, A., and Narkiewicz-Jodko, W. (2001). Alexithymia in schizophrenia: an exploratory study. Psychological Reports, 89(1), 95-98.

- Dawson, S., Kettler, L., Burton, C., and Galletly, C. (2012). Do people with schizophrenia lack emotional intelligence? Schizophrenia Research and Treatment. doi:10.1155/2012/495174.

- Eack, S. M., Greeno, C. G., Pogue-Geile, M. F., Newhill, C. E., Hogarty, G.E., and Keshavan, M. S. (2010). Assessing social-cognitive deficits in schizophrenia with the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36(2), 370-380.

- Eack, S. M., Pogue-Geile, M. F., Greeno, C. G., and Keshavan, M. S. (2009). Evidence of the factorial variance of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test across schizophrenia and normative samples. Schizophrenia Research, 114(1-3), 105-109.

- Edwards, J., Jackson, H. J., and Pattison, P. E. (2002). Emotion recognition via facial expression and affective prosody in schizophrenia: a methodological review. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(6), 789-832.

- Extremera, N., and Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2009). Test de Inteligencia Emocional Mayer-Salovey- Caruso (MSCEIT): manual. Madrid: TEA Ediciones.

- Hafner, H., Maurer, K., Loffler, W., Van der Heiden, W., Hambretch, M., and Schultze-Lutter, F. (2003). Modeling the early course of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 29(2), 325-340.

- Kee, K. S., Green, M. F., Mintz, J., and Brekke, J. S. (2003). Is emotion processing a predictor of functional outcome in schizophrenia? Schizophrenia Bulletin, 29(3), 487-497.

- Kee, K. S., Horan, W. P., Salovey, P., Kern, R. S., Sergi, M. J., Fiske, A. P.,… and Green, M. F. (2009). Emotional intelligence in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 107(1), 61-68.

- Kimhy, D., Vakhrusheva, J., Jobson-Ahmed, L., Tarrier, N., Malaspina, D., and Gross, J. J. (2012). Emotion awareness and regulation in individuals with schizophrenia: implications for social functioning. Psychiatry Research, 200(2), 193-201..

- Kohler, C. G., Turner, T. H., Bilker, W. B., Brensinger, C., Siegel, S. J., Kanes, S. J.,… and Gur, R. C. (2003). Facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: intensity effects and error pattern. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(10), 1768-1774..

- Kring, A. M., Barrett, L. F., and Gard, D. E. (2003). On the broad applicability of the affective circumplex: representations of affective knowledge among schizophrenia patients. Psychological Science, 14(3), 207-214.

- Kring, A. M., and Caponigro, J. M. (2010). Emotion in schizophrenia: where feeling meets thinking. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(4), 225-259.

More references from the article on emotional intelligence in schizophrenia:

- Kring, A. M., and Earnst, K. S. (1999). Stability of emotional responding in schizophrenia. Behavior Therapy, 30(3), 373-388.

- Lizzeretti, N. P., Extremera, N., and Rodríguez, A. (2012). Perceived emotional intelligence and clinical symptoms in mental disorders. Psychiatric Quarterly, 83(4), 407-418.

- Mandal, M. K., Pandey, R., and Prasad, A. B. (1998). Facial expressions of emotion and schizophrenia: a review. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24(1), 399-412.

- Matthews, G., Zeidner, M., and Roberts, R. D. (2007). Emotional intelligence: consensus controversies, and questions. In G. Mathews, M. Zeidner and R.D. Roberts. (Eds). The science of emotional intelligence: knows and unknowns. Series in affective science (pp. 3-46). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Mayer, J. D., and Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey and D. Sluyter (Eds). Emotional development and emotional intelligence: implications for educators (pp 3-31). New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., and Caruso, D. R. (2002). Mayer- Salovey- Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT): USER´s Manual. Toronto, ON: Multi- Health Systems Inc.

- Nuechterlein, K. H., and Green, M. F. (2006). MATRICS consensus battery manual. Los Angeles, CA: MATRICS Assessment Inc

- Nuechterlein, K. H., Green, M. F., Kern, R. S., Baade, L. E., Barch, D. M., Cohen, J. D.,… and Marder, S. R. (2008). The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 1: test selection, reliability and validity. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(2), 203- 213

- Sanders, A., and Szymanski, K. (2012). Emotional intelligence in siblings of patients diagnosed with a mental disorder. Social Work in Mental Health, 10(4), 331-342.

- Scholten, M. R., Aleman, A., Montagne, B., and Kahn, R. S. (2005). Schizophrenia and processing of facial emotions: sex matters. Schizophrenia Research, 78(1), 61-68

- Sifneos, P. E. (1973). The prevalence of “alexithymic” characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 22(2-6), 255-262.

- Stanghellini, G., and Ricca, V. (2010). Alexithymia and schizophrenias. Psychopathology, 28(5), 263-272

- Tremeau, F., Malaspina, D., Duval, F., Correa, H., Hager-Budny, M., Coin-Bariou, L.,… and Gorman, J. M. (2005).Facial expressiveness in patients with schizophrenia compared to depressed patients and nonpatient comparison subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(1), 92-101.

- Van der Meer, L., Van’t Wout, M., and Aleman, A. (2009). Emotion regulation strategies in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 170(2-3), 108-113.

- Van’t Wout, M., Aleman, A., Bermond, B., and Kahn, R. S. (2007). No words for feelings: alexithymia in schizophrenia patients and first-degree relatives. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48(1), 27-33.

- Wojtalik, J. A., Eack, S. M., and Keshavan, M. S. (2013). Structural neurobiological correlates of Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test in early course schizophrenia. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 40, 207-212.

- Yecker, S., Borod, J. C., Brozgold, A., Martin, C., Alpert, M., and Welkowitz, J. (1999). Lateralization of facial emotional expression in schizophrenic and depressed patients. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 11(3), 370-379

- Yu, S., Li, H., Liu, W., Zheng, L., Ma, Y., Chen, Q.,… and Wang, W. (2011). Alexithymia and personality disorder functioning styles in paranoid schizophrenia. Psychopathology, 44(6), 371-388.

- Yung, A. R., and McGorry, P. D. (1996). The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 22(2), 353-370

If you liked this post about emotional intelligence in schizophrenia, we recommend you take a look at these NeuronUP publications:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Inteligencia emocional en esquizofrenia: Déficits en esquizofrenia

How does insomnia affect our executive functions?

How does insomnia affect our executive functions?

Leave a Reply