Dr. Carlos Rebolleda, PhD in Psychology, explains the deficits of theory of mind in schizophrenia and the tests for its assessment.

The term “theory of mind” was initially proposed by Premack and Woodruff (1978) and refers to the individual’s ability to infer others’ mental states such as intentions, dispositions and beliefs.

Assessment of theory of mind in schizophrenia

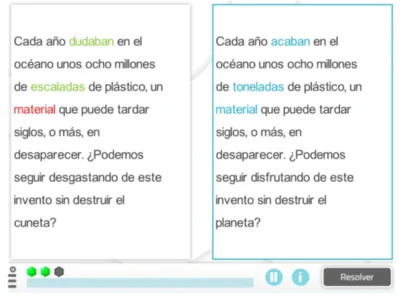

Ruiz, García and Fuentes (2006) point out that generally the tests aimed at measuring theory of mind are usually presented in the form of comics or short stories about which certain questions are later asked. These questions aim to evaluate two types of false beliefs in relation to the story.

Types of questions

First-order questions

First-order questions are intended to assess to what extent the evaluated subject is able to predict the behavior of a character acting based on a false belief, Sally and Anne (Baron-Cohen, Leslie and Frith, 1985) and Cigarretes (Happè, 1994) would be examples of stories that pose first-order questions.

Second-order questions

Second-order questions assess to what extent the evaluated subject is able to predict the false belief that one character has about another character’s belief, Ice- Cream Van Store (Baron-Cohen, 1989) and Burglar Store (Happè and Frith, 1994) are tests created for posing second-order questions.

Hinting Task

One of the most used instruments in psychosis research is the Hinting Task (Corcoran, Mercer and Frith, 1995) which comprises ten short stories in which an interaction between two characters takes place. All these stories end with a hint from one of the characters to the other. The objective of the task is that, after the evaluator reads the different stories, the subject tries to explain what the character issuing the hint is trying to say.

Faux Pas Task

The Faux Pas Task (Stone, Baron-Cohen, Calder and Keane, 1998) presents the subject with ten stories in which one of the characters makes a mistake by saying something that is socially embarrassing. After presenting each of the stories to the subject, they are asked to detect the socially embarrassing situation and assess how the other character may have felt.

The test requires the subject to have the capacity to detect false beliefs in the case of the person who makes the socially embarrassing mistake, and to infer emotional states according to how they consider the character who received the verbalization may have felt.

Eye-Task

Eye-Task (Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, Raste and Plumb, 2001), consists of showing participants several photographs in which only the eyes of a subject are shown, asking them to infer what the person may be feeling or thinking. To make this assessment, the participant can only choose one of the four words offered as options.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Deficits of theory of mind in schizophrenia

The differences found in performance in this area by patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and control subjects are substantial, as highlighted by two meta-analyses that find effect sizes ranging from medium (d=0.69) to large (d=1.25) for these differences (Bora, Yucel and Pantelis, 2009; Sprong, Schothorst, Vos, Hox and Van Engeland, 2007).

Research hypotheses

Historically, researchers have tried to study to what extent the symptoms of schizophrenia determine the deficits that people diagnosed with this disorder present in theory of mind.

Some studies support the hypothesis that the subject must present a theory of mind without deficits of any kind in order to develop persecutory delusional ideas (Drury, Robinson and Birchwood, 1998; Watson, Blenner-Hasset and Charlton, 2000).

Others indicate that patients who show negative or disorganized symptomatology never developed a theory of mind, an aspect that can be observed in the poorer performance they show when faced with tasks that require the use of this ability (Garety and Freeman, 1999; Greig, Bryson and Bell, 2004)

Objective of the research

A current objective in the study of deficits in theory of mind in schizophrenia is to identify whether these deficits resemble a trait or a state of the disorder, as it would help resolve whether they are exclusively associated with the symptoms of the disorder.

It is noteworthy that the bulk of the research carried out in this regard indicates that these deficits would constitute a trait characteristic of the disorder (Herold, Tenyi, Lenard and Trixler, 2002; Irani et al., 2006; Janssen, Krabbendam, Jolles and Van Os, 2003; Penn, Sanna and Roberts 2008).

Although studies such as Bora et al. (2009) show that, despite these deficits appearing to remain present at any stage of the disorder, it is not known to what extent the neurocognitive problems in working memory and executive functions, or the residual symptomatology itselfl, the factors that really contribute to the maintenance of these.

It therefore seems necessary to continue researching in this direction before being able to state that such deficits constitute a trait of the disorder.

Neurological perspective

At the neurological level, Rodríguez and Touriño (2010) point out that neuroimaging studies with healthy subjects have found that some brain areas such as the prefrontal area, the amygdala or the inferior parietal lobe are activated during tasks in which theory of mind has to be put into practice (Brunet, Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Decety, 2000; 2003). In the case of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, a decrease in activation in the right prefrontal cortex and in the left inferior frontal gyrus has been found during the performance of tasks of this type (Adolphs, 2002; Brunet et al., 2000).

Bibliography

- Adolphs, R. (2002). Neural systems for recognizing emotion. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 12(2), 1-9

- Baron- Cohen, S. (1989). The autistic child´s theory of mind: a case of specific developmental delay. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 30(2), 285-297

- Baron- Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M., and Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a theory of mind? Cognition, 21(1), 37-46

- Baron‐Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., and Plumb, I. (2001). The “Reading the mind in the eyes” test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with asperger syndrome or high‐functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(2), 241-251.

- Bora, E., Yucel, M., and Pantelis, C. (2009). Theory of mind impairment in schizophrenia: meta- analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 109 (1-3), 1-9

- Brunet, E., Sarfati, Y., Hardy-Bayle, M. C., and Decety, J. (2000). PET investigation of the attribution of intentions with nonverbal task. Neuroimage, 11(2), 157-166

- Brunet, E., Sarfati, Y., Hardy-Bayle, M. C. and Decety, J. (2003). Abnormalities of brain function during a nonverbal theory of mind task in schizophrenia. Neuropsychologia, 41(12), 1574-1582.

- Corcoran, R., Mercer, G., and Frith, C. D. (1995). Schizophrenia, symptomatology and social inference: investigating “theory of mind” in people with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 17(1), 5-13.

- Drury, V. M., Robinson, E. J., and Birchwood, M. (1998). Theory of mind skills during an acute episode of psychosis and following recovery. Psychological Medicine, 28(5), 1101-1112

- Garety, P. A., and Freeman, D. (1999). Cognitive approaches to delusions: a critical review of theories and evidence. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(2), 113-154.

- Greig, T. C., Bryson, G. J., and Bell, M. D. (2004). Theory of mind performance in schizophrenia: diagnostic, symptom and neuropsychological correlates. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192(1), 12-18

- Happè, F. (1994). An advanced test of theory of mind: understanding of story characters thoughts and feelings by able autistics, mentally handicapped and normal children and adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(2), 129-154

- Happè, F., and Frith, U. (1994). Theory of mind in autism. In E.Schloper and G.Mesivob (Eds). Learning and Cognition in Autism (pp.177-197). NuevaYork, NY: Plenum Press

- Herold, R., Tenyi, T., Lenard, K., and Trixler, M. (2002). Theory of mind deficit in people with schizophrenia during remission. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 1125-1129

- Irani, F., Platek, S. M., Panyavin, I. S., Calkins, M. E., Kohler, C., Siegel, S. J.,… and Gur, R. C. (2006). Self-face recognition and theory of mind in patients with schizophrenia and first-degree relatives. Schizophrenia Research, 88(1-3), 151-160.

- Janssen, I., Krabbendam, L., Jolles, J., and Van Os, J. (2003). Alterations in theory of mind in patients with schizophrenia and non-psychotic relatives. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 108(2), 110-117

- Penn, D. L., Sanna, L. J., and Roberts, D. L. (2008). Social Cognition in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(3), 408-411

- Premack, D., and Woodruff, G. (1978). Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(4), 515-526.

- Rodríguez, J. A., and Touriño, R. (2010). Social cognition in schizophrenia: a review of the concept. Archivos de Psiquiatría, 73, 9-12

- Ruiz, J. C., García, S., and Fuentes, I. (2006). The relevance of social cognition in schizophrenia. Apuntes de Psicología, 24(1-3), 137-155

- Sprong, M., Schothorst, P., Vos, E., Hox, J., and Van Engeland, H. (2007). Theory of mind in schizophrenia: meta- analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(1), 5-13.

- Stone, V. E., Baron-Cohen, S., Calder, A. W., and Keane, J. (1998). Impairments in social cognition following orbitofrontal or amygdale damage. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts, 24, 1176

- Watson, F., Blenner-Hasset, R. C., and Charlton, B. G. (2000). Theory of mind, persecutory delusions and the somatic marker mechanism. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 5(3), 161-174.

If you liked this post about theory of mind in schizophrenia, you may be interested in these NeuronUP articles.

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Teoría de la mente en la esquizofrenia

Mental Math Worksheet: «Hit the Target Right»

Mental Math Worksheet: «Hit the Target Right»

Leave a Reply