Marcos Ríos-Lago highlights the advances, opportunities and limits of technology in the field of neuropsychological assessment, with a critical and integrative perspective.

The ubiquity of technology in our lives

Currently we are surrounded by technology. Just a few days ago we experienced a blackout that left us without electricity for several hours and made it possible to outline the consequences of not having the technology to which we are accustomed. Industry, entertainment, transportation, communications and a myriad of everyday elements as simple as cooking or having hot water stopped working. Technology surrounds us in practically every aspect of our lives.

Why has neuropsychology been slow to digitize?

However, some authors have recently pointed out that there are disciplines in which the use of technology is still symbolic and has not been incorporated into everyday work as much as would be possible. We are certainly talking about neuropsychology, as Miller and Barr (2017) have indicated.

Despite its potential advantages and the high level of technology use in other areas, neuropsychology has not yet made a full transition toward the incorporation of technological elements that have long been adopted in other related areas in the field of rehabilitation.

First steps toward digital transformation in rehabilitation

It is true that in the field of rehabilitation computer use for cognitive stimulation is more common, and NeuronUP is a good example of this. We have also begun to carry out remote sessions, something that proved a great advantage during the pandemic period and allowed the continuation of treatments for those who could not travel to rehabilitation centers temporarily. This is of immediate application in rural and underserved settings.

The APA guidelines for telepsychology establish ethical, technical and psychometric principles for remote neuropsychology via videoconference (American Psychological Association, 2013). Also, the use of digital tools is already available in electronic health records, given current information protection needs.

Neuropsychological assessment: still far from digitization

However, the use of technology in neuropsychological assessment is only in its beginnings, and its implementation is very limited, despite its potential.

Classic tests: the pillars of clinical neuropsychology

At the beginning of the 20th century, interest in understanding the functioning of the human mind and the nervous system led to the development of some experimental tasks such as what is today known as the Stroop test (1935), the Trail Making Test (1948), or Rey’s memory tests (1919) or the Rey Complex Figure (1941) (for a review see Sherman, Tan and Hrabok, 2022).

Some time later, these tasks began to be used in the clinical setting with the aim of characterizing the cognitive profile of patients with some type of central nervous system impairment. These tests have become the gold standard in clinical practice.

Why do we keep using tests designed 100 years ago?

Almost 100 years later we still use these tasks in everyday clinical practice. However, over all these years tasks have continued to be designed that are allowing us to deepen and increase our knowledge about cognition and the brain, but they have not made the leap to the clinical field.

If we have the “best” tasks to understand brain functioning and cognitive processes, why not use them day-to-day with our patients?

Advantages of paper-and-pencil tests

Neuropsychologists are well acquainted with classic paper-and-pencil tests. Today we know that they allow us to evaluate the performance of the mechanisms we know today (and that do not always coincide with those for which, according to knowledge from 100 years ago, they were designed).

Many allow us to make reasonably standardized observations to test our cognitive models and, above all, to observe and diagnose people’s behavior (many of them with some type of cognitive impairment for different reasons). In addition, they offer solid norms that allow us to relate an individual’s performance to different reference groups by age, educational level, disease, etc. Certainly, we use them every day and can clearly see their advantages (and some of their disadvantages as well).

Digitization of neuropsychological assessment: a new era

Today we have the possibility to fully introduce digitization into neuropsychological assessment. This digitization of assessment not only responds to the urgency of modernizing century-old protocols, but opens up a range of possibilities that transcend the mere translation to electronic format of classic tests.

First stage: conversion of protocols

The conversion of classic protocols to electronic formats can constitute the first stage of digitization. In this phase, instructions and administration criteria are replicated, incorporating automatic scoring and new temporal and kinematic metrics (latencies, pauses, touch pressures, tremor, etc.).

These new measures can help detect microvariations in the order of strokes and in the applied pressure, indicators possibly sensitive to cognitive decline and subtle alterations.

Also the use of variability metrics or response consistency can help unravel attentional fluctuations imperceptible in the classic format (Harris et al., 2024).

Of course, in this area would be the incorporation of tasks from basic neuroscience and neuropsychology research that may be useful in the clinical setting, thus reclaiming part of our discipline’s tradition in its origins.

The clinician’s role in the digital age

Right now, the mere capture of quantitative data lacks interpretive meaning, so a high level of knowledge on the part of the professional is necessary. The interpretation of results continues to depend largely on the clinician’s expertise: scoring norms, the application of heuristics in reasoning, criteria for discarding items and diagnostic inferences require a high level of experience.

However, we must reflect on our own knowledge. For example: ‘Are we experts in traumatic brain injuries?’, ‘and how expert are we with a patient who has suffered a trauma following an unsuccessful suicide attempt?’, ‘are we good at handling the consequences of a trauma in a person affected by severe depression?’.

Perhaps being able to count on contextual support systems or automated suggestions can improve our evaluative and therapeutic capacity.

Second stage: incorporation of hardware

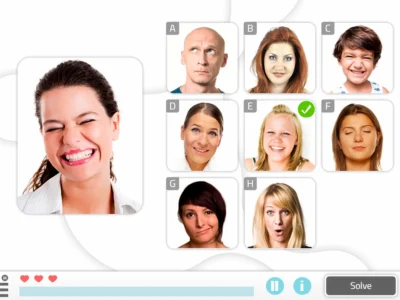

A possible second stage would incorporate additional hardware: accelerometers, haptic sensors, motion sensors, eye-trackers, cameras for facial recognition, virtual and augmented reality environments.

Bello et al (2025) conclude that these technologies remain underutilized despite their potential to recreate instrumental activities of daily living with high fidelity.

Using some of these technologies it may be possible to record reactions of frustration, anticipatory anxiety, or the ability to detect one’s own errors. All of this is today at the mercy of the professional’s ability to detect and interpret it appropriately.

Areas such as social cognition, interpersonal conflict resolution or emotion detection remain scarcely explored territories with high-resolution quantitative tools. And, in a globalized world, the lack of cross-cultural comparisons and versions adapted to different linguistic and educational contexts weakens the ecological validity of many instruments.

Wearables y mobile-health en neuropsicología

But, returning to technology that is already established and surrounds us, we can highlight the so-called wearables, which allow us to record information in real time and in natural environments (Fioerdelli et al. 2013).

Since the appearance of the iPhone in 2007 research in mobile-health has increased exponentially, highlighting remote monitoring, frequent data collection in natural environments, health promotion and intra-individual longitudinal comparisons.

Neuropsychology is not fully employing the possibilities of this data collection in natural settings. This includes voice, movement, route recordings, etc. In addition, the use of mobile phones also allows immediate feedback to the individual, the use of scheduled messaging, the optimization of alarms and reminders (for example, geolocated), the use of the camera and microphones, voice recognition, as well as other functionalities of interest for neuropsychology (Gómez Velez et al. 2017).

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Third stage: integration of AI

The third and most disruptive stage could be the integration of unified platforms with artificial intelligence (AI). The rapid rollout of various AI tools in recent months and their adoption by the population could cause this phase to occur sooner than expected.

The existence of natural language processing systems and their accessibility is accelerating the use of, at least, some of their functionalities. Nevertheless, it will be useful to delve deeper into this technology.

Diagnostic and intervention possibilities

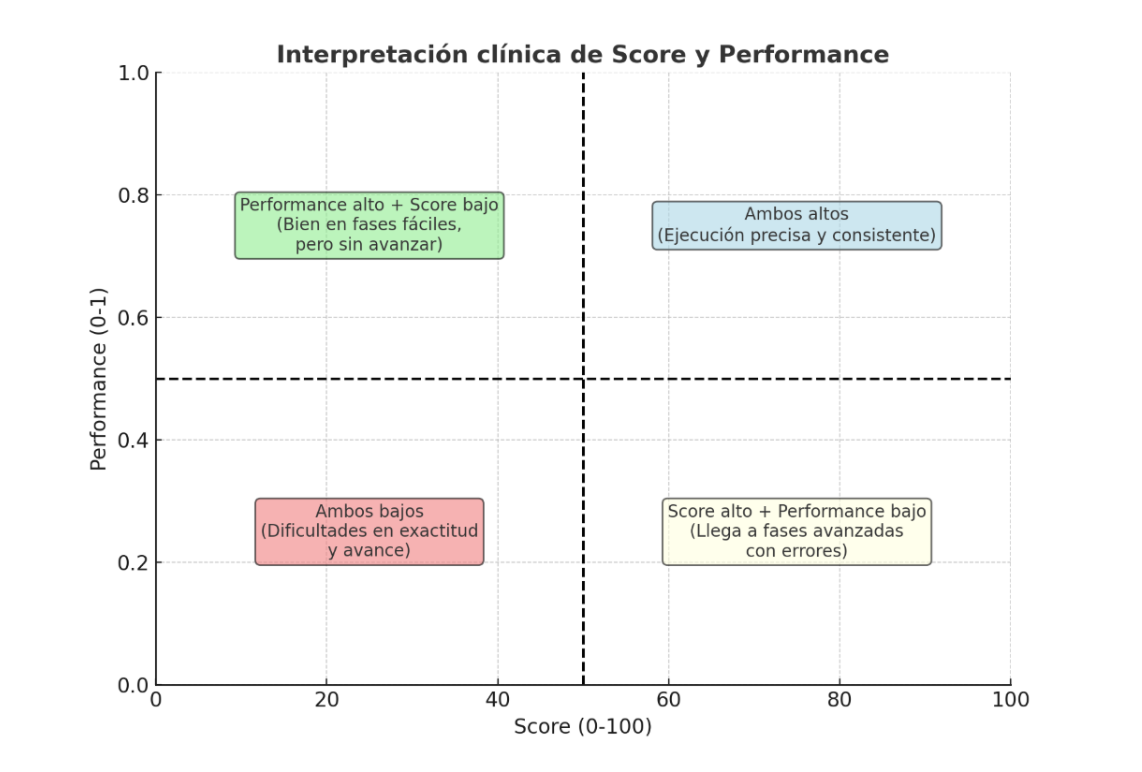

Supervised and unsupervised learning algorithms can process thousands of variables (kinematics, reaction times, error patterns), analyzing complex response patterns, identifying atypical cognitive profiles, detecting prognostic markers or proposing neuroanatomical inferences with accuracies that surpass expert judgment in certain specific tasks (Veneziani et al., 2024).

Automated report generation

In addition, these systems can generate reports that integrate clinical narratives, performance charts and intervention recommendations (cognitive rehabilitation, pharmacological adjustments) in seconds, significantly reducing decision-making time, the need for treatment changes, and even the preparation of reports without decreasing (or even increasing) their quality.

Normative databases and diagnostic personalization

An essential aspect for the proper functioning of these tools is the construction of large multicenter normative databases, with cross-cultural validation and data that allow adjustment for different parameters (age, educational level, comorbidities, etc.), enabling the personalization of diagnoses and cut-off points.

Ethical considerations and regulatory challenges in the digitization of neuropsychology

Nevertheless, the transition to this neuropsychology 3.0 involves regulatory and ethical challenges (Bilder, 2011; Harris et al., 2024).

The GDPR requires encryption, anonymization and traceability in the management of sensitive data. Also, approval of AI-based tools by agencies such as the EMA or the FDA is still incipient.

However, beyond this, there is a fundamental element that does not fall to these institutions or to the corresponding legislator, but to those of us who generate, teach and use this technology: continuous learning, correct use and knowledge of its limits and capabilities.

Only with responsible and appropriate use do these technologies make us better. We cannot delegate our tasks and responsibilities to language models, but we can use them as a tool that expands our possibilities and closely supervise the results they offer. This requires constant learning, in addition to what we as neuropsychology professionals were already obliged to.

Conclusion: toward a more precise, ecological and personalized neuropsychology

The central message seems clear to me: to overcome the inertia of the past and meet the clinical demands of the 21st century, it is necessary to embrace intelligent digitization that respects psychometric rigor, enhances diagnostic sensitivity and opens paths toward truly ecological and personalized assessments.

Thus neuropsychology will be able to faithfully assess complex human behavior and offer precision interventions that improve the quality of life of those suffering cognitive impairments.

None of this, moreover, is incompatible with the careful and close observation of the people who come to us for their assessments and treatments. We are facing an important challenge in which we must integrate the past with the future (present, actually). This train has already left. It is up to us to get on it and lead it or wait for others to do it for us.

Bibliography

- American Psychological Association. (2013, July). Guidelines for the practice of telepsychology. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/telepsychology-revisions

- Bello, K., Aqlan, F., & Harrington, W. (2025). Extended reality for neurocognitive assessment: A systematic review. Journal of psychiatric research, 184, 473–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2025.03.034

- Bilder RM. (2011). Neuropsychology 3.0: evidence-based science and practice. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS, 17(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617710001396

- Harris C, Tang Y, Birnbaum E, Cherian C, Mendhe D, Chen MH. (2024) Digital Neuropsychology beyond Computerized Cognitive Assessment: Applications of Novel Digital Technologies, Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 39 (3), 290-304. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acae016

- Gómez A, Nieto López S, González Rey N and Ríos Lago M. (2017) The use of mobile phones in the rehabilitation of brain injuries. Informaciones psiquiátricas. 229. 53-77

- Miller JB and Barr WB (2017). The Technology Crisis in Neuropsychology. Archives of clinical neuropsychology, 32(5), 541–554. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acx050

- Sherman EMS, Tan JE and Hrabok M, (2022). A compendium of neuropsychological tests: Fundamentals of Neuropsychological Assessment and Test Reviews for Clinical Practice (4th Ed). Oxford University Press

- Veneziani, I., Marra, A., Formica, C., Grimaldi, A., Marino, S., Quartarone, A., & Maresca, G. (2024). Applications of Artificial Intelligence in the Neuropsychological Assessment of Dementia: A Systematic Review. Journal of personalized medicine, 14(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14010113

If you liked this blog post about the digitization of neuropsychological assessment, you will likely be interested in these NeuronUP articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

La digitalización en la evaluación neuropsicológica

Hippocampal Atrophy: Differences Between Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s

Hippocampal Atrophy: Differences Between Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s

Leave a Reply