Neuropsychopedagogue Juan Carlos Cancelado Rey explains in this article the neuropsychology of aphasias from a process model, focusing on the definition, characteristics, symptoms and affected processes of Broca’s aphasia and Wernicke’s aphasia.

Neuropsychology of aphasias from a process model: “I never thought speaking would be so difficult” Broca, “what’s wrong with them that they don’t understand me?” Wernicke

Language, although it is a human faculty for communicating through articulation to speak, its relevance lies in how it shapes the mind and allows it to express itself to others. Therefore, it would be appropriate to present language as a cognitive function that operates together with other functions and integrates processes jointly.

This will help us better understand what, in clinical practice, is complicated to differentiate when deciding who is aphasic and who is not. Since there is no physical trait that can generate a clinical representation of a specific or global aphasic picture, or that it is part of its semiology. In a way, although it may seem paradoxical, the way to know it is through the phonatory effort to speak and understand; if applicable, whether the patient must perform it correctly or, on the contrary, whether the interlocutor has difficulty understanding it or knowing what the patient wants to communicate.

What are Aphasias?

Aphasias denote those alterations of language as a sequela of acquired brain injury, which affect the ability for verbal communication at the expressive, receptive and/or global level (Ardila, 2005).

The Boston school, whose representatives Goodglass and Kaplan (2002) define them as impairments in articulation, production and comprehension of language that are not compatible with a muscular incoordination or paralysis of physiological etiology.

However, the diagnostic labels of Broca or Wernicke do not specifically describe the patient’s cognitive process profile, due to many overlaps, but they become a tool for communication in daily clinical practice among professionals and to know what to expect. In this way, it is possible to go into more detail about the cognitive deficits that accompany the patient’s primary impairment.

Language processes: anatomopathological relationship and aspects of neuropsychological assessment

The language processes of Ellis and Young (1992) allow differentiation of central aspects, such as errors made by patients with acquired brain injury or in patients with language impairment of neurodegenerative etiology.

1. Repetition

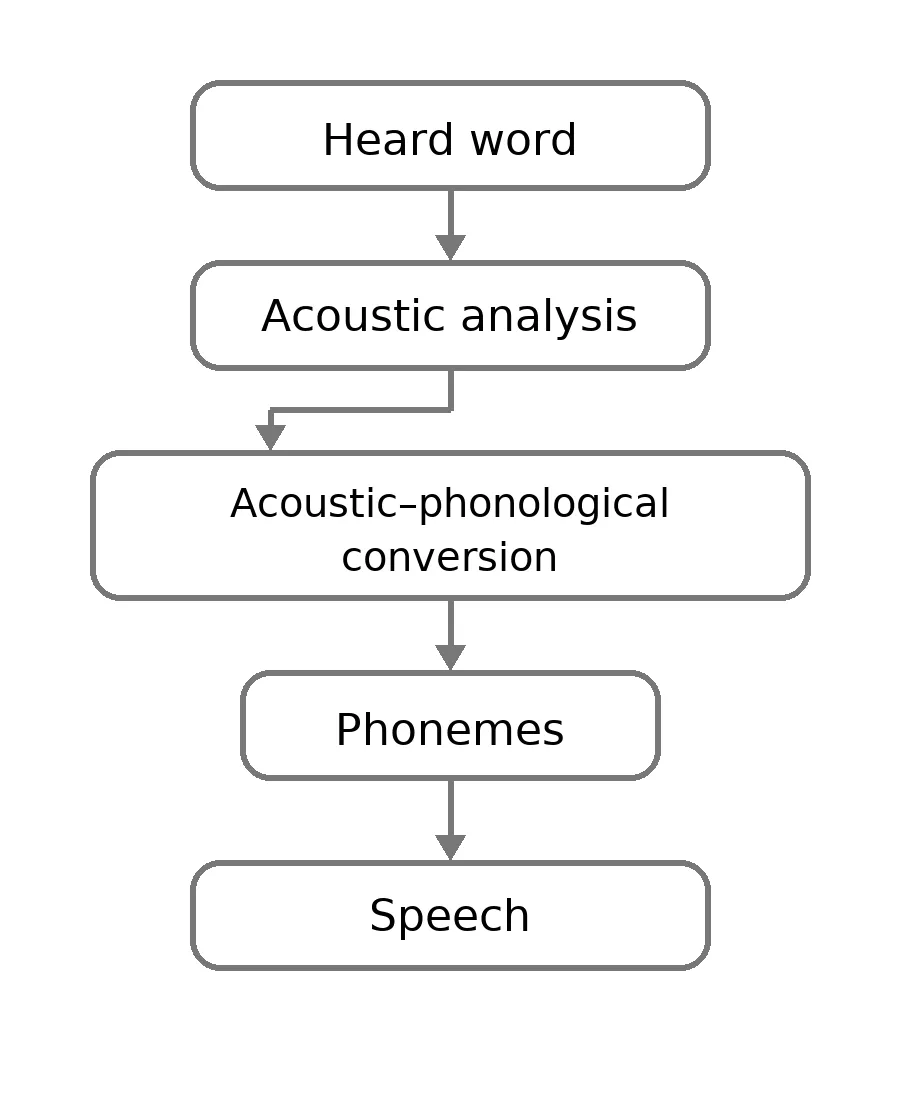

At birth we already come programmed with a certain orientation toward language. Perceptual systems such as the auditory system are modulated as they mature and maintain a relationship with the environment. This process is responsible for transforming acoustic information into phonological information.

However, here it is important to consider other underlying processes such as the lexical and semantic store, and the relationship that exists with the phonological loop of working memory.

In this sense, that mechanism referred to is of vital importance for language learning and is called acoustic-phonological conversion from the cognitive model understood in terms of processes.

Following the dual-route model of Gregory Hickok and David Poeppel (2004), the repetition process maintains a close anatomopathological relationship with involvement of the dorsal or sublexical route, with clear lateralization to the left hemisphere, where the phonological information processed is sent along this route to produce the articulatory response, originating in sensorimotor integration areas and passing through the articulatory network of the angular gyrus, arcuate fasciculus and Broca’s area for articulatory movement. In addition, the superior longitudinal fasciculus is important in repetition and phonological aspects, being relevant in relation to the phonological loop of working memory.

The assessment of the repetition process is usually carried out both:

- qualitatively during the anamnesis with the patient;

- with tests that evaluate syllables, syllable pairs, nonwords, pairs of words with phonological relation and sentences.

Bearing in mind that both the test and the clinical observation can lead us to specify the type of aphasia as well as which process is affected.

2. Comprehension

In the early years of life the increase in comprehension as an expression of language is exponential; the growth of the phonological lexicon, as a semantic store through relationships and experiences with the environment, becomes automatic. Words and meanings are acquired at a speed that enables information processing such as acoustic-phonological analysis to be fed with experience and emotions over time.

Thanks to the formation of a lexical-phonological store, the relationship between the heard word, the acoustic analysis, the input phonological lexicon and the semantic system (Vega, 2012) allows the person to:

- understand words and auditory codes as textual;

- strengthen the grammatical architecture of their expressive language, maintaining order, intonation, lexicon, phonetic, syntactic and semantic sense when articulating it.

Dual-route model

The dual-route model of Gregory Hickok and David Poeppel (2004) states that the ventral route, located in different portions of the temporal lobe, has a special function in lexical and semantic processes. If the uncinate fasciculus (which connects anterior temporal structures and inferior frontal areas) is compromised, comprehension of complex syntactic structures can be affected. While damage to the arcuate fasciculus could be relevant for signs of inability to comprehend the meaning of isolated words.

In this sense, qualitative data from a good anamnesis and clinical observations as well as the appropriate choice of tests that allow evaluation of visuo-visual, visuo-verbal and/or verbal-verbal tasks contribute to the assessment.

As an objective, it would be advisable to assess with all possible types of tasks, since this way we can differentiate whether the comprehension deficit corresponds to a primary alteration or is secondary to other affected processes.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

3. Production

The idea of producing language begins with the need to convey. The more capable our phonological and semantic stores are, the more articulated language can be generated.

When we talk about production we emphasize a direct route that lacks meaning, through the mechanism of acoustic-phonological conversion and another route for producing semantic content.

This helps us understand the dissociation we see in some patients between their ability to repeat but not to produce language spontaneously and vice versa. In addition, it leads to the importance of assessing repetition of pseudowords and real words separately, since these are processed by different routes.

In this order of ideas, in language production, it is expressed grammatically correctly to adequately convey its syntactic, phonological, phonetic, lexical and semantic value. Otherwise, we could observe it clinically and in neuropsychological assessment tests administered to the patient.

The generating routes are usually the dorsal routes explained above in dual-route processes (Gregory and Poeppel, 2004).

Language assessment tests

However, it is necessary to understand that language assessment must be taken into account throughout the evaluation process, since the person’s spontaneous language is an important source of information (Lezak et al., 2012). Consequently, we can determine their capacity for acoustic-phonological discrimination, comprehension (semantic store: what information is intended to be conveyed?, lexical store: “appropriate word”, phoneme choice), fluency and speech production.

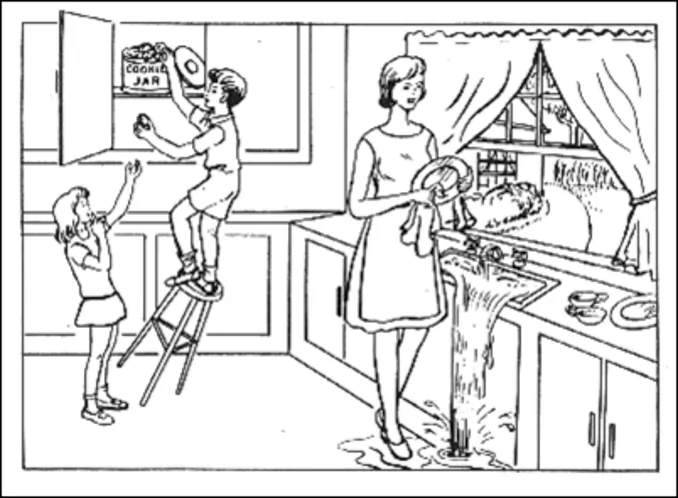

Three types of tests are usually used for its assessment:

- Direct question tests,

- description of a picture,

- answers to a question about an exciting historical topic.

In this way, the assessment of articulatory skill, grammatical form and prosody is usually evaluated with the Boston test.

Some authors give greater importance to the sentence length produced by the person since it allows better quantification and establishing normal cutoffs in sentences, for example, nine-word sentences in a single expiration without pauses (Helm-Estabrooks and Albert, 2005).

4. Naming

Naming is a central symptom of aphasia. Problems in naming an object appear according to the processes that have been affected. This is known as anomia in language, which is often considered to be only an access problem to information, with circumlocutions and some paraphasias.

Types of anomia

In practice, it is known through observations and assessments with patients that three types of anomia can be distinguished (Fernández and Vega, 2006):

1. Access anomia

In this type of anomia the patient often manifests a phenomenon called “on the tip of the tongue”, due to the inability to access the word even though they know it. However, when a phonological cue is given to the patient they usually recall it completely.

For example, helping them to name table when the examiner indicates and gives the cue:

— Examiner: Starts with ’em’,

—Patient: Ah, I have it! It’s table, it’s table!

This type of anomic aphasia is usually difficult to locate anatomically, although there could be several causes for access naming problems. For example, problems in more frontal retrieval processes; among others that correlate with white matter.

2. Semantic anomia

In this type of anomia we find that the patient recognizes the objects they must name, but does not have the word to signify them. Thus, when it is pointed out to the patient that it is a “chair” they respond with surprise, for example:

— Examiner: It is a chair.

—Patient: Chair? Is this called a chair?

Their surprise corresponds to a vocabulary reduced compared to what would be expected.

This type of anomia is usually related to anterior temporal regions due to their verbal semantic function.

3. Phonological anomia

In this type of anomia phoneme selection is often incorrect in the patient’s verbal expression. They do not access the word, and their production is generated through syllabic approximations with an error in the first syllable, for example:

—Patient: It’s a torne…torci…tornito… Screw!

The angular gyrus often has a relationship with this type of anomia due to the phonological component.

Assessment of anomia is usually carried out with the Boston Naming Test (Kaplan et al., 1978) or the DO-80 oral picture naming test (Deloche and Hannequin, 1997).

Up to this point, it has been necessary to explain the previous processes to facilitate the understanding of a Broca aphasic picture and a Wernicke aphasia, without falling into the dichotomy of the lesion model, in which Broca is known as the one who cannot speak and Wernicke as the one who does not understand, overlooking, of course, articulatory and verbal errors in Broca and phonological errors in Wernicke.

In this way, following the perisylvian aphasic syndromes, that is, language defects located around the Sylvian fissure of the left hemisphere, composed of the three main aphasic syndromes (Broca, conduction and Wernicke), we will facilitate understanding of the two syndromes studied, Broca and Wernicke. This is because their semiology can be varied depending on whether the involvement is more anterior, medial or posterior to the perisylvian area.

Broca’s aphasia

“I never thought speaking would be so difficult“

Also known as efferent aphasia or kinetic aphasia (Luria, 1970), expressive aphasia (Hécaen and Albert, 1978), verbal aphasia (Head, 1926) and Broca’s aphasia (Benson, 1979).

What is Broca’s aphasia?

This syndrome comprises impairments in language fluency.

Characteristics of Broca’s aphasia

Broca’s aphasia is characterized by:

- reduced expressive language,

- impaired repetition,

- short and agrammatical utterances,

- production problems related more to verbs than to nouns.

- it is usually localized in the more inferior frontal-lateral areas surrounding the Sylvian fissure, anterior to the prerolandic fissure (Brodmann areas 44 and 45).

Articulatory verbal errors of Broca’s aphasia

- Phonological simplifications: simplification of the syllabic structure and in repetition. For example, the patient says “tes” instead of “tres” (three).

- Anticipation: the patient says, for example, “lelota” instead of “pelota” (ball).

- Perseveration: an error of more than one consonant tends to persist. For example, pronounces “pepo” instead of “peso” (weight).

- Substitution of fricative phonemes: replaces (f, s, j) with plosives (p, t, k). That is, they say “plor” instead of “flor” (flower).

- Agrammatism: the agrammaticality in Broca’s aphasia production shows defective sentence comprehension by altering its grammatical order. Thus the patient could say instead of “the dogs are in the garden”, “dog garden”. Agrammatism and anomia in Broca’s aphasia usually result from subcortical lesions involving damaged vascular territories that affect the middle cerebral artery or the neocortex in the inferior frontal lobe.

Processes impaired in Broca’s aphasia

Regarding the processes impaired in Broca’s aphasia:

- spontaneous language is not fluent; the patient tends to produce it with effort using single words and short phrases;

- the phonetic and phonological process presents dysarthria, omits phonemes, reduces consonant clusters and uses phonological paraphasias;

- morphosyntax tends to be agrammatical and telegraphic. They present aprosody and auditory verbal comprehension is relatively preserved; however, by not relating grammatical components the disorganized language does not allow sentence comprehension;

- naming is of a phonological anomia that improves with syllabic cues;

- repetition is impaired;

- reading aloud is defective, with comprehension similar to oral, showing agrammatism, slow speech (bradylalia), fragmented and difficult;

- writing: presents spelling errors, omissions and substitutions of graphemes.

The signs we find of alterations in language processes in a Broca’s aphasia can be translated in practice by the presence of patients who speak and make themselves understood but maintain small articulation or comprehension errors, as already mentioned this can also occur in Broca’s aphasia. Other patients are definitely difficult to understand, their language is not fluent and there is a loss of automatization in speech articulation; others may present a more marked phonological anomia which improves with phonetic cues provided to them, and thus each of these patients may both articulate language and produce the sentence (with defects) or may not.

Bibliography

- Ardila, A., Rosselli, M., Márquez Orta, E., & Rodríguez Flores, L. (2007). Clinical neuropsychology. Mexico, D.F.: Manual Moderno. https://colombia.manualmoderno.com/catalogo/neuropsicologia-clinica-9786074488074-9786074488135.html

- Ardila, A. (2005). Aphasias. Mexico. University of Guadalajara. https://elrincondeaprenderblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/libro-las-afasias-alfredo-ardila.pdf

- Helm-Estabrooks, N. and Albert, M. L. (2005). Manual of aphasia and aphasia therapy. Editorial Médica Panamericana. https://www.casadellibro.com.co/libro-manual-de-la-afasia-y-de-terapia-de-la-afasia-2-ed/9788479038335/1019320

- Lezak, M., Howieson, D. and Loring, D. (2012). Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford University Press (5th ed.). https://global.oup.com/academic/product/neuropsychological-assessment-9780195395525?cc=co&lang=en&

- Nakase-Thompson, R., Manning, E., Sherer, M., Yablon, S. A., Gontkovsky, S. L. T. and Vickery, C. (2005). Brief assessment of severe language impairments: initial validation of the Mississippi aphasia screening test. Brain Injury, 19(9), 685-691. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16195182/

If you liked this article about the neuropsychology of aphasias from a process model: Broca’s Aphasia and Wernicke’s Aphasia, you might also be interested in reading these blog posts:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Neuropsicología de las afasias desde un modelo de procesos: «Nunca pensé que hablar fuera tan difícil», Afasia de Broca, «¿qué les pasa que no me entienden?», Afasia de Wernicke

The Blue Zones and the Secret of Longevity

The Blue Zones and the Secret of Longevity

Leave a Reply