Default Mode Network (DMN) can be defined as a baseline of neuronal activity [1] that occurs when the subject has thoughts that are not goal-directed. It was discovered from the degree of variation in oxygen consumption in a series of brain areas that activated when people were not thinking about “anything in particular” (this is important). Another factor that has been used to study this network is the synchrony (the degree of coordination of the frequencies emitted by neurons as a consequence of their electrical activity). To give an analogy, imagine old radio receivers broadcasting on the same frequency (or on several that couple) and firing at the same time to communicate on a large scale.

In the typical DMN experiment, subjects are asked to close their eyes and not think about anything in particular, simply to stay awake. Then magnetic resonance images (or other techniques) are taken of the brain regions of interest. Afterwards, subjects are asked to carry out a task that requires goal-directed thoughts and/or behaviors (an executive demand).

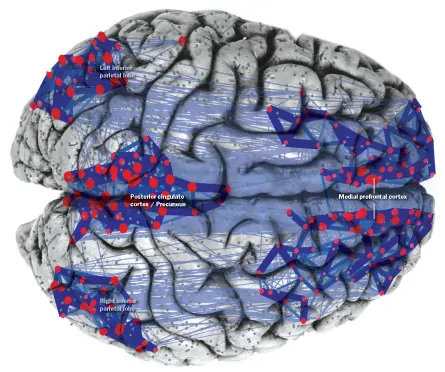

These are the areas that activate in the “resting” situation (DMN):

In the image we can see how, in addition to the dark blue areas, there are more diffuse traces that connect these areas. They are white matter tracts and help us understand that the brain’s networks are configured as “small-world” networks: distributed centers connected on a large scale across the brain. These networks evolve with maturation; in the early years of life they do not show as much cohesion [2]. Among the areas that activate are:

– The medial prefrontal cortex, an area that includes Brodmann Areas 9 and 10, among others. These two areas have been related to representations of our personality and social cognition.

– The precuneus (ventral), related to episodic memory, consciousness and the self. Also with visuoconstructive abilities.

– The inferior parietal lobe, related to language, body image and emotion identification. Also with spatial representation.

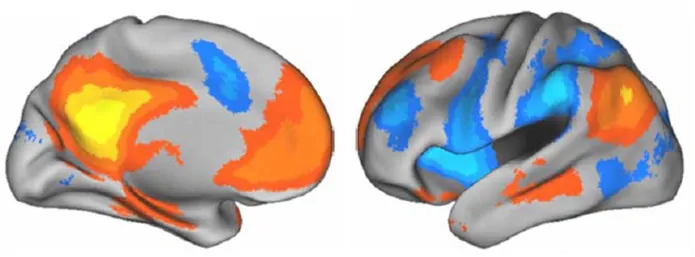

When brain activity is contrasted in both situations (when one “doesn’t think about anything” vs. when one has a goal-directed thought/problem-solving) a similar image to the one above is obtained. The blue areas correspond to regions activated when the person executes a task (Task Network). The orange areas would be the DMN. The interesting thing is that execution of the executive task correlates with proper activation of the task network (“blue”) and a proper attenuation (which does not reach full deactivation) of the DMN (“orange”). Do we have an example of the sought-after “double dissociation” in neuropsychology?

Don’t think about anything in particular?

In reality, when the researcher asks that one not think about anything in particular for a period of time, we do something. In the first place we do not lose awareness of ourselves. Generally, subjects in experiments during this experimental condition have reported that they think about themselves (self, personality), about things they have to do (prospective memory) or about events that have happened to them (episodic memory). Even about abstract concepts (semantic concepts) that may or may not be connected.

What is the relationship between the DMN and Alzheimer’s disease?

The Alzheimer’s disease is a syndrome of neuronal disconnection. This disconnection affects small-world networks and their large-scale communication. In the case of the DMN, the integrity of the network is compromised by the deterioration of the posterior cingulate cortex and therefore the connectivity between the medial frontal region and the inferior parietal lobe. The consequence is an incorrect activation of the DMN, but also the existence of longer networks and therefore less efficient ones (depending on the method used to study the phenomenon). Sporns [3] mentions that the precuneus is also an area particularly vulnerable to amyloid protein deposition. The lack of integrity of the DMN is a biomarker in Alzheimer’s disease.

The cognitive consequence of this is the inability to bind the cognitive contents from the previous section: intentional search in memory, loss of spatial schemas – both bodily and non-bodily –, loss of abstract concepts, loss of personality. All of this, progressively.

What is the relationship between the DMN and schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia can be conceptualized as a syndrome of disconnection, disintegration and desynchronization. We can see it in fronto-temporal connections, due to structural deficits but also in white matter connectivity at a large scale and in small-world networks. The “manifestation” of this can be seen in different cognitive aspects. Not only in working memory. Also a disconnection of language (mutism, intrusion of ruminations during task execution, echolalia, disorganized speech, etc.), of personality, consciousness, thought or body schema.

In schizophrenia there are also alterations in the efficiency of networks at the large-scale level of the brain. What is the effect on the DMN? It is twofold. A deficit in the inhibition of the DMN occurs. And when there is an incorrect suppression of the DMN, the “task network” does not work properly [4]. From this could arise, for example, the typical intrusions of some people with schizophrenia during the execution of ADLs.

What is the relationship between the DMN and autism?

In autism, in general terms, we can say that there is also an incorrect suppression of the DMN, as well as a low overall activity of this network and poor self-referential processes. In addition, and unlike the previous syndromes, there could be an opposite profile in which small-world networks are overconnected, producing a lack of differentiation of large-scale networks. This generates a loss of integration of the processes in which they are involved.

To learn more:

- Raichle, M. E., MacLeod, A. M., Snyder, A. Z., Powers, W. J., Gusnard, D. A., & Shulman, G. L. (2001). A default mode of brain function.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,98(2), 676 682. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.2.676

- Fair, D. A., Cohen, A. L., Dosenbach, N. U. F., Church, J. A., Miezin, F. M., Barch, D. M., Raichle, M. E., etal. (2008). The maturing architecture of the brain’s default network.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,105(10), 4028 4032. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800376105

- Sporns, O. (2011) Networks of the Brain. Ed. MIT

- Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., Thermenos, H. W., Milanovic, S., Tsuang, M. T., Faraone, S. V., McCarley, R. W., Shenton, M. E., etal. (2009). Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,106(4), 1279 1284. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809141106

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

La red en reposo. Implicaciones en Alzheimer, esquizofrenia y autismo

The Remains of a Shipwreck: Emotional Memory and Alzheimer’s

The Remains of a Shipwreck: Emotional Memory and Alzheimer’s

Leave a Reply