Carlos Ruiz Ramírez, a specialist in cognitive physical training, presents how neuroscience applied to sports performance shows that training the brain is key to optimizing attention, decision-making, and motor efficiency.

Introduction

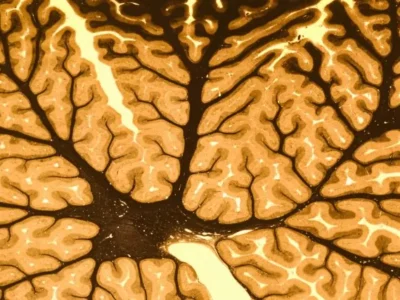

Seen from the stands, sport looks like a choreography of muscles: running, jumping, striking, enduring. But beneath every visible gesture beats an invisible machinery: billions of neurons creating maps of the world in real time, adapting to chaos, predicting the unpredictable. Understanding this universe is not only the task of scientists; it is also the task of those who want to discover how the brain transforms uncertainty into mastery and energy into beauty.

The role of the brain in cognitive performance

The body executes, but it is the brain that composes the score. Every time a footballer shapes up to receive a pass, his brain is performing a feat: it synchronizes muscles, interprets visual signals, calculates distances, evaluates risks, predicts opponents’ and teammates’ intentions. All of that in less than half a second.

This phenomenon is possible because the brain does not operate as a linear chain of commands, but as a complex network. Within it, thousands of systems (sensory, motor, emotional, attentional) interact in a non-hierarchical, self-organized and dynamic way. There is no single “control center”, but multiple nodes conversing in parallel.

That mode of operation is what enables sports creativity. The unexpected goal, the improvised feint, the impossible pass: none are planned rationally; they emerge from the organized chaos of the brain. And the most fascinating thing is that this chaos can be trained.

Instead of trying to eliminate unpredictability from practice, the trainings that best develop cognitive performance are those that introduce variability, surprise and uncertainty. Because disorder is not the enemy of performance, it is its engine.

Neuroplasticity and adaptation in sport: keys to high performance

The sporting environment is, by definition, changing. A bad bounce of the ball, a gust of wind, an opponent who alters their tactic… Nothing stays the same. And the player who masters the game is not the one who memorizes the most plays, but the one who adapts fastest to what is new.

Neuroscience explains it through neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to reorganize its neuronal connections in response to new challenges (Merzenich et al., 2014). The more an athlete is exposed to novel stimuli, the more flexible their neural network becomes and the more resources they have to solve problems in real time.

This has very powerful practical implications:

- Excessively predictable training creates rigid automatisms.

- Trainings that include variability, decision-making and time pressure foster flexible brains.

A classic study in sports science showed that when athletes practice in unpredictable environments, they retain what they learn better and transfer their skills more successfully to real competition contexts (Davids et al., 2008).

To adapt, in essence, is not to resist change, but to flow with it.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Perception and attention in sport: the gateway to decision-making

In sport, acting half a second before the opponent can change an outcome. That fraction of time depends less on physical speed and more on perceptual speed.

Experts don’t see more than others, they see differently. They organize sensory information to detect relevant patterns and discard the irrelevant. In football, for example, elite players scan the environment far more frequently before receiving the ball, which allows them to anticipate and decide more effectively (Jordet et al., 2013).

Sports perception is an active and trainable process. It is shaped through tasks that integrate peripheral vision, divided attention, working memory and inhibitory control. These executive functions (governed by the prefrontal cortex) are the same ones we use in daily life to plan, solve problems and manage emotions.

Thus, training scanning on the playing field is also training the brain for everyday life. It’s not just about watching the ball; it’s about reading the world while everything moves.

Cognitive and energy efficiency in sport: how to optimize mental and physical resources

The brain represents barely 2% of body weight, but consumes around 20% of resting energy. During exercise, that demand is shared with

muscles hungry for oxygen and glucose. If the brain does not optimize its expenditure, the body tires prematurely.

Here appears the concept of neural energy efficiency. Expert athletes don’t run more, they run better. They automate motor patterns, regulate effort, choose key moments to accelerate and moments to recover, and in doing so free up cognitive resources to make decisions.

This balance between conscious control and automation reflects the cooperation between the central nervous system (motor cortex, basal ganglia, cerebellum) and the autonomic nervous system, which regulates vital functions and activation states.

Science confirms it: training with tasks that simultaneously demand physical effort and decision-making improves both neural efficiency and physical performance (Pesce & Audiffren, 2011).

In other words, the best athlete is not the one who does more, but the one who does just enough with the right amount of energy.

Cognitive training in sport: beyond the muscle

Neuroscience does not seek to turn coaches into neuroscientists or players into walking laboratories. It seeks something simpler and deeper: that we understand that sports performance is an emergent phenomenon, the result of multiple systems interacting harmoniously under conditions of uncertainty.

For that reason, designing trainings focused only on mechanical repetition is like teaching painting with only one brush: it ignores the full palette. When we train from complexity, we allow the athlete to learn to think in motion, adapt to chaos, perceive accurately and manage their energy as a finite resource.

And that same model applies to any human being. Life, like sport, is unpredictable. Those who cultivate a flexible, perceptive and efficient brain can transform everyday uncertainty into opportunity. And that, at bottom, is winning.

Think fast, decide better: memory and executive functions from sport to everyday life

Strength moves, but memory holds the plan. In a match, working memory (that mental notepad that lasts seconds) keeps alive the map of supports, coverages and passing lanes while the world shakes. The central midfielder who receives “in position” does not see only a ball: they hold in their head the coach’s last instruction, the winger’s movement two seconds ago and the gap that will open if they draw pressure one touch more. That instant memory is what allows playing for the future.

Episodic memory stores experiences and trains intuition: “when the opposing full-back closes, the pass behind appears.” And procedural memory automates technical gestures to free up attentional resources: the less ball control occupies you, the wider the lens to decide. The same happens in life: whoever automates habits (sleeping, eating, prioritizing) spends less on the basics and chooses better in the complex.

To that orchestra executive functions are added, the skills of the “playmaker”, the brain:

- Inhibitory control: not everything I can do should be done. The No. 9 who does not shoot at first touch and waits for the midfielder to arrive; the goalkeeper who does not kick quickly because they see the team is disorganized. In everyday life, it is not responding to the first emotion and choosing the right moment.

- Cognitive flexibility: changing plan without losing composure. The winger who was going to take on down the line sees the full-back’s support and cuts inside. In life, it is recomputing when the context changes without warning.

- Planning: prioritize what matters right now. The center-back who, upon hearing “only!”, rewrites his hierarchy of options in milliseconds: pause, carry, break the line. Off the field, it is adjusting the schedule when the essential appears.

These functions are trained in contexts rich in information, with clear rules and intelligent variability. A good exercise does not seek the perfect play, but brains that choose.

In short: memory to remember what is useful, executive functions to choose what is necessary, and complexity to learn to flow. Good football (like good life) is not about defeating chaos, but about conversing with it until the game returns harmony to you.

Movement: the highest expression of life

Movement is the way life speaks. Every step, every gesture, every change of direction is a small act of rebellion against rigidity. To be alive is to move, and to move is to adapt. Charles Darwin summed it up with a phrase that crosses time: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one that best adapts to change.”

In sport —and in life— to adapt is not to resist nor to give up, it is to flow. And flowing requires moving with awareness, not only with speed. Each time an athlete moves, their brain is filtering thousands of stimuli: voices, colors, trajectories, distances, sounds, internal and external pressures. The key is not to process them all, but to know which ones matter and which to let go.

That ability to discriminate the relevant from the irrelevant is the true muscle of adaptation. It is called selective attention, and it depends on circuits that connect the prefrontal cortex with sensory and limbic systems. The more we train our gaze to widen the field and wisely choose what to attend to, the more flexible we become in the face of uncertainty.

Moving, then, is not just displacing through space; it is learning to inhabit change without fear. Because whoever moves with wide-open eyes and sharpened judgment stops fighting the environment and begins to flow with it.

And when we flow with the world, the world ceases to be a threat and becomes a vast stage.

Conclusion: the importance of the brain in performance and daily life

Neuroscience reminds us that sports performance does not depend only on the body that runs, but on the brain that adapts. The more complex the environment, the sharper perception becomes; the more uncertainty, the more plastic the mind becomes; the better the chaos is predicted, the less energy is wasted.

Understanding this web is not only useful for winning matches: it teaches us to live with intelligence, flexibility and elegance in a world that never stops moving. Because training the brain is not only improving performance, it is expanding the possibilities of what we can become.

Sport is not just a competition against others, it is a mirror that confronts us with the unpredictable: error, chance, the chaos that no plan can control. Every training session is a rehearsal of how to respond when the planned breaks. And in that swing between order and disorder, between control and surprise, character is forged. Because the true challenge is not to impose our will on the world, but to maintain our essence when the world changes without warning (read it like a match). That, perhaps, is the true triumph: not to defeat the opponent, but to overcome uncertainty without losing harmony.

Bibliography

- Davids, K., Button, C., & Bennett, S. (2008). Dynamics of Skill Acquisition: A Constraints-Led Approach. Human Kinetics.

- Jordet, G., Bloomfield, J., & Heijmerikx, J. (2013). Scanning, context and decision making in elite soccer players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 31(4), 431–440.

- Kelso, J.A.S. (1995). Dynamic Patterns: The Self-Organization of Brain and Behavior. MIT Press.

- Leon C. Megginson (1963), inspired by On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin (1859).

- Merzenich, M. M., Van Vleet, T. M., & Nahum, M. (2014). Brain plasticity-based therapeutics. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 385.

- Pesce, C., & Audiffren, M. (2011). Cognitive and physical exercise: Bio-psycho social outcomes. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(6), 1119–1121.

Frequently asked questions about neuroscience and cognitive stimulation in sport

1. What is cognitive stimulation in sport?

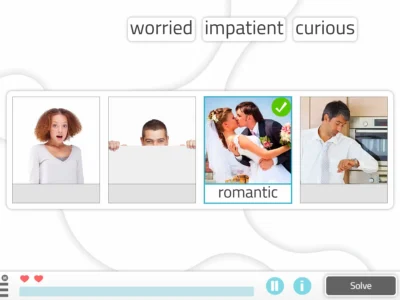

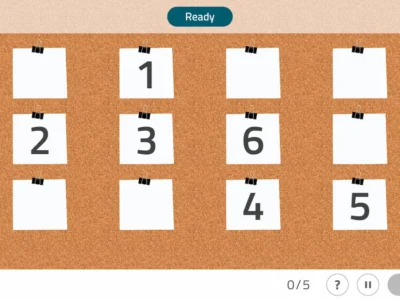

Cognitive stimulation in sport consists of training mental functions such as attention, memory, perception or decision-making to improve performance. Through exercises that combine movement and mental challenge, the athlete learns to anticipate, adapt and maintain concentration even under pressure.

2. Why is neuroscience key to high sports performance?

Neuroscience applied to sport studies how the brain coordinates action, perception and emotion during training and competition. Understanding these processes allows optimizing both physical and cognitive preparation, favoring smarter, more efficient and sustainable performance.

3. What benefits does cognitive stimulation have for athletes?

Cognitive stimulation improves decision-making, selective attention, working memory and mental flexibility. In the sporting context, this translates into better game reading, anticipation of opponents, less mental fatigue and greater capacity to adapt to uncertainty. In addition, it strengthens emotional resilience and prevents cognitive exhaustion.

4. What role does neuroplasticity play in sports performance?

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to reorganize its neuronal connections in response to new stimuli. In sport, it translates into greater adaptation to changing environments, better motor learning and greater transfer of skills between training and competition.

5. How to apply cognitive stimulation in sports training?

It can be applied through dual exercises that combine physical effort and mental challenge: tasks that demand divided attention, inhibitory control, working memory or decision-making under pressure. For example, games with variable visual and auditory stimuli, changes of pace or peripheral vision exercises. These dynamics develop the cooperation between the central nervous system and the motor system, key in cognitive-sport performance.

6. Which executive functions are essential for sports performance?

The key executive functions are inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility and strategic planning. Training them allows regulating impulses, adapting to unforeseen changes and prioritizing effective decisions, both on the field and off it.

If you enjoyed this article about neuroscience and cognitive stimulation in sport, you will likely be interested in these NeuronUP articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Más cerebro, menos desgaste: el secreto oculto del alto rendimiento

Late Diagnosis of Autism in Women: How to Recognize Specific Signs and Adapt Cognitive Stimulation

Late Diagnosis of Autism in Women: How to Recognize Specific Signs and Adapt Cognitive Stimulation

Leave a Reply