Child and adolescent neuropsychologist Alba Martínez addresses in this article the neurodevelopmental disorders from a gender perspective.

1. Introduction

Neurodevelopmental disorders are a heterogeneous group of conditions that affect cognitive, behavioral and socioemotional development from early stages of life. Despite advances in research, a significant gap remains in the identification, diagnosis and treatment of these conditions when analyzed from a gender perspective (Young et al., 2020).

2. What are neurodevelopmental disorders?

According to the DSM-5-TR® (APA, 2022), neurodevelopmental disorders include conditions such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), intellectual developmental disorder, communication disorders, specific learning disorder, motor disorders and tic disorders, among others.

These are conditions of biological origin that affect the development of the central nervous system and manifest from the earliest stages of growth. These alterations directly impact the development of functions such as interaction and social cognition, language, learning and attention.

Although they may coexist with other diagnoses, they share a fundamental characteristic: they appear in development and persist across the lifespan. For this reason, early diagnosis and intervention are essential to reduce functional impact and improve adaptation to the environment.

Despite this, there are crucial factors such as gender biases or the sociocultural context that influence directly and indirectly. Recognizing the importance of these contextual and social components promotes a comprehensive approach adjusted to diversity.

3. Gender differences in ASD, ADHD and intellectual disability

The clinical presentations of neurodevelopmental disorders are not gender-neutral. However, research and clinical practice have been based mainly on male populations, which has contributed to a biased understanding and systematic underdiagnosis in girls, women and people with diverse gender identities (Young et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2015).

In the case of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), its presentation may make the identification of early signs more difficult that can differ from the traditional clinical profile (García and Reyes, 2025), signs such as (Ruggieri et al., 2016):

- Fewer disruptive behaviors and more skills for social imitation (and sometimes even greater social interest).

- Camouflaging or masking, and adaptation to the environment.

- Restricted interests that are more socially accepted (such as music groups or TV series).

- Compliant attitudes and apparent emotional regulation.

In attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a higher diagnostic rate in boys has been observed, partly because:

- Externalizing symptoms such as hyperactivity or impulsivity are more readily identified —which reinforces the stereotype of the “disruptive boy who fails”.

- In girls the symptoms tend to be more internalizing and less evident: hyperactivity may present in a contained or verbal form, and attention difficulties may be mistaken for lack of motivation, immaturity or emotional aspects (anxiety, depression, etc.).

We also find gender differences in intellectual disability (ID) which, in turn, is also usually identified with more externalizing and disruptive symptoms that are more evident and obscure more subtle expressions. In women, girls and/or diverse groups these are more associated with:

- Internalizing or apparently adaptive symptoms that may be wrongly attributed to lack of effort, shyness or dependence, preventing proper and early diagnosis.

In fact, in many cases diagnoses can be confused between the different neurodevelopmental disorders, especially in female profiles. For example, it is common for girls and women on the spectrum to be misdiagnosed with ADHD, or for an intellectual disability to mask features of the spectrum. These diagnostic confusions are closely related to gender differences in the clinical expression of these disorders.

Furthermore, sometimes if a girl with a neurodevelopmental disorder presents more externalizing behaviors such as hyperactivity, impulsivity or disruptive behaviors, her case is often interpreted as more severe or more interfering. However, this assessment does not always reflect the clinical reality, but is influenced by prejudices, social expectations and gender stereotypes about how girls “should” behave.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

4. Gender gap in the diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders

Historically, clinical models and diagnostic criteria have been built from studies focused mainly on male population samples. This has generated a significant bias in the identification of symptomatology in girls, women and people with diverse gender identities, which contributes to underdiagnosis or late diagnosis in this population.

Regarding prevalence, the CDC (2023) estimates that there is a 4:1 prevalence favoring males for ASD and 3:1 for ADHD. Although it is true that in recent years the prevalence of ASD has increased, partly thanks to improved diagnostic tools and its definition, including consideration of the gender perspective.

Despite this, lower visibility of symptoms highlights the gender gap in diagnosis. As a result, many girls, women and people with diverse gender identities receive incorrect, late or no diagnoses at all.

The gap widens even more when other social variables such as socioeconomic level, sexual orientation, gender expression, among others, are taken into account, as they influence the visibility of these conditions. For example, adolescents undergoing gender transition or children in contexts of social vulnerability face greater challenges and obstacles to being evaluated and receiving appropriate treatment.

To address this gap, a critical perspective is necessary: we must examine ourselves as professionals, analyze the diagnostic tools we use and work on our training, incorporating the gender perspective transversally. In this way, we can move toward more equitable, sensitive care tailored to each person’s needs.

4.1 Neurodevelopmental disorders underdiagnosed in women

The direct consequence of this gap is that many women, girls and people with diverse identities do not receive a diagnosis, or receive it late. Underdiagnosis entails the absence of appropriate supports during key developmental stages, which can lead to emotional disorders, low self-esteem, school failure, regulation difficulties, other comorbid disorders or problems in adulthood such as limited access to resources or difficulties with workforce integration (Rivière, 2018).

In neurodevelopmental disorders, many women reach adulthood without having been diagnosed, or are mislabelled with disorders such as anxiety, depression or borderline personality disorder. This diagnostic overlap can lead to inadequate interventions that perpetuate distress and social exclusion.

For example, in the case of ASD, ADHD or ID, research has shown that many girls use camouflaging or masking and compensatory strategies that hinder early detection (Hull et al., 2019). These strategies include, on the one hand, copying body language, facial expressions, learning from films, books, AI, among other sources. Using strategies to hide characteristics or traits or forcing interactions with others to adapt to the environment.

4.2 The importance of early diagnosis and the impact of late diagnosis in girls and adolescents

Early diagnosis is a key protective factor. Intervening in time makes it possible to design specific strategies that enhance the capacities of people with neurodevelopmental disorders and prevent comorbidities.

In girls, late diagnosis can have particularly negative consequences during adolescence, when social and emotional demands increase. In addition, lack of understanding of one’s own functioning can negatively influence identity construction and the development of self-concept.

In general, these differences are not only purely neurobiological factors, but are modulated by social and gender expectations that impact the clinical perception of symptoms of neurodevelopmental disorders. Often, the environment demands constant adaptation that implies sustained overexertion, which can generate comorbidities or associated problems that mask the underlying condition, such as low self-esteem, self-harm, eating disorders (ED), personality disorders or other secondary clinical presentations.

In fact, one of the comorbidities that is currently seen daily in mental health centers and that, therefore, delays diagnosis, is the appearance or confusion of a neurodevelopmental disorder with an eating disorder. Traits such as cognitive rigidity, sensory sensitivities or hyperactive behaviors are identified that can be interpreted as characteristic of an eating disorder and not of an underlying neurodevelopmental disorder (Tchanturia, 2017).

5. Neuropsychological assessment with a gender perspective

Neuropsychological assessment is a key tool for diagnosis and intervention planning. However, if it does not incorporate a gender perspective, it can contribute to reinforcing existing biases and gaps.

Assessing with a gender perspective means going beyond traditional tests: it is not only about measuring memory, attention or language, but also about understanding how girls, women and people with diverse identities may express or camouflage their symptoms differently.

In practice, this implies:

- Including qualitative observations,

- observing behavior in natural contexts,

- interviewing family members and teachers,

- reviewing school and social history,

- and using tools that are not limited to the “male” or prototypical profile and that adapt to different cognitive styles.

5.1 How to incorporate a gender perspective into neuropsychological assessment

Some strategies to incorporate this perspective include:

- Use of flexible diagnostic criteria: Do not assume that the absence of typical behaviors rules out a diagnosis if there are other relevant signs. For example, in ADHD, having a learned capacity for organization does not mean the absence of attentional difficulties.

- Consider internalizing symptoms: Pay attention to signs such as social anxiety, mental fatigue or withdrawal, which are more frequent in girls.

- Assessment of camouflaging strategies: Detect behaviors that aim to mask difficulties, such as copying social behaviors, avoiding conflicts, overstudying to compensate for reading difficulties or avoiding tasks that require sustained attention.

- Active involvement of family and school: Obtain different perspectives on the person’s daily functioning (for example “she came home exhausted from school”, “she made lists and collections about animals or music groups”, “she avoided reading aloud”, “she is the last to leave class”)

- Incorporate tools and review psychometric tests: review new algorithms or norms, use questionnaires such as the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire CAT-Q (Hull et al., 2019) for social camouflaging or assess socioemotional competencies for example with the Social Responsiveness Scale SRS-2 (Constantino et al., 2012) and measures of adaptive behavior.

5.2 Neuropsychological intervention strategies adapted to gender

Once the diagnosis is established, it is essential that the intervention also takes gender differences and each person’s particularities into account. Strategies must be personalized, promoting self-esteem, authentic social skills and emotional self-regulation, avoiding reinforcing traditional roles that limit autonomy and taking into account how gender and social expectations influence.

For girls and adolescents, it is key to validate their experiences and avoid overloads derived from camouflaging or self-demand. For example: if a student with ADHD completes school tasks but arrives home exhausted, the intervention should include training in effort regulation and active breaks, not only organizational techniques.

- In ASD, an adolescent who appears to function socially may be using exhausting imitation strategies, so it is advisable to foster adaptive social skills and anxiety management.

- In learning difficulties, a student who spends extra hours memorizing may need to retrain reading speed and use visual summaries to avoid overload.

- In ID, a young person who appears autonomous in the classroom may require more supports to plan and carry out tasks outside that environment, fostering autonomy and avoiding overprotection.

Collaboration with family and school must translate into concrete actions (adapted visual schedules, routines to stimulate executive functions, emotional self-regulation strategies) and feedback focused on real progress, not on behavioral stereotypes.

6. The importance of gender-differentiated intervention

Designing gender-differentiated interventions implies recognizing how the social and cultural context modulates the experience of neurodevelopmental disorders. Girls may feel pressured to “fit in” and hide their difficulties, which can generate emotional fatigue, self-regulation difficulties and comorbid disorders.

- In ASD, it involves training genuine social skills;

- in ADHD, managing energy and attention to avoid exhaustion;

- in ID, enhancing autonomy without overprotection; and in learning disorders, combining technological supports with validation of effort.

A gender-focused intervention promotes emotional support environments, safe spaces for identity development and social networks that favor well-being. The intervention must empower, create a safe environment for identity development and promote functional resources, not just compensate for deficits.

The daily challenge for clinicians, teachers and families is to detect subtle signs that gender stereotypes can hide. Incorporating this perspective into daily practice makes it possible to reveal inequalities and move toward more sensitive, effective and inclusive interventions, remembering that what is seen does not always reflect reality.

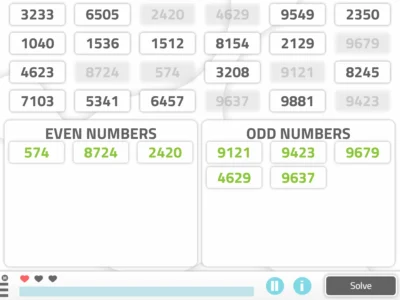

7. How NeuronUP can support personalized intervention in neurodevelopmental disorders

NeuronUP, with its extensive catalog of activities, allows interventions to be adapted to individual needs, considering the neuropsychological profile and learning style of each person.

Integrating it into our practice makes it easier to adjust the intervention to each profile, promoting a therapeutic environment that is dynamic, inclusive and free of bias, which optimizes the potential of users, especially.

With NeuronUP, professionals can:

- Design flexible intervention programs adjusted to the cognitive and emotional profile.

- Monitor progress continuously, allowing rapid and personalized adjustments.

- Select specific activities to enhance executive functions, attention, language or social cognition, adjusted to the individual performance level.

- Apply engaging content that increases motivation, striving to reduce gender bias that avoids reproducing stereotypes and promoting active participation of all profiles.

8. Conclusion

Neurodevelopmental disorders are complex realities that, far from presenting homogeneously, are deeply influenced by biological, social and cultural factors, including gender. Ignoring these differences not only perpetuates diagnostic and intervention biases, but also deprives many people of supports that could make an important difference in their life trajectory.

For too long, the voice of girls, women and people with diverse identities has been sidelined and distorted by a clinical gaze filtered by stereotypes and expectations. Daily they face a double challenge: coping with the difficulties of their condition and, at the same time, adapting to an environment that often invisibilizes their needs or misinterprets their signals, making them feel “lost”.

Integrating the gender perspective helps us see the invisible, and to learn to notice what often goes unnoticed: recognizing that a compliant smile can hide great exhaustion, that silence can be a sign of an internal struggle and that “seems to be adapting well” or “you can’t tell” can imply a high emotional cost. Incorporating it into our daily work is an ethical and professional requirement.

Advancing toward this more inclusive model does not mean asking them to function differently, but that they can show themselves as they are and create environments that promote their well-being. This requires questioning ourselves, being critical, learning and listening to what is sometimes not always said out loud. Neurodevelopmental disorders do not speak a single language: they are expressed with accents, nuances and silences that, if we do not know how to listen, may escape us.

Bibliography

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., text revision).

- CDC. (2023). Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2012). Social Responsiveness Scale – Second Edition (SRS-2). Western Psychological Services.

- García, G. F., & Reyes, M. H. (2025) Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder with a gender perspective. Elementos 138 11-116

- Hull, L., Mandy, W., Lai, M. C., Baron-Cohen, S., Allison, C., Smith, P., & Petrides, K. V. (2019). Development and validation of the camouflaging autistic traits questionnaire (CAT-Q). Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 49, 819-833.

- Lai, M.-C., Lombardo, M. V., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Sex/gender differences and autism: setting the scene for future research. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.003

- Rivière, A. (2018). The development of autism: an evolutionary and neuropsychological perspective. Autismo Ávila.

- Ruggieri, V. L., & Arberas, C. L. (2016). Autism in women: clinical, neurobiological and genetic aspects. Rev Neurol, 62(suppl 1), S21-26.

- Tchanturia, K., Leppanen, J., & Westwood, H. (2017). Characteristics of autism spectrum disorder in anorexia nervosa: A naturalistic study in an inpatient treatment programme. Autism, 23(1), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317722431

- Young, S., Moss, D., Sedgwick, O., Fridman, M., & Hodgkins, P. (2020). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in incarcerated populations. Psychological Medicine, 45(2), 247–258.

Frequently asked questions about gender perspective and neurodevelopmental disorders

1. What are neurodevelopmental disorders?

Neurodevelopmental disorders are biological conditions that affect the development of the central nervous system from early stages, impacting functions such as attention, language, social interaction and learning. They include autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), intellectual disability (ID), communication disorders and learning disorders.

2. Why is the gender perspective important in the diagnosis of ASD and ADHD?

The gender perspective allows identification of differences in symptom presentation between girls and boys, preventing less visible signs from being overlooked. In girls, ASD and ADHD may manifest with fewer disruptive behaviors and more internalizing symptoms, which contributes to underdiagnosis.

3. What are the symptoms of ASD in girls that can go unnoticed?

Some signs include camouflaging or masking, restricted interests that are socially accepted, compliant attitudes, skills for social imitation and apparent emotional regulation. These traits can make early detection difficult if only traditional clinical profiles are sought.

4. What is camouflaging or masking in ASD and why does it hinder diagnosis?

Camouflaging or masking is a conscious or unconscious strategy to hide social or sensory difficulties. In girls and women with ASD, it can include copying gestures, memorizing social scripts or forcing interactions. This delays diagnosis and increases the risk of fatigue and emotional comorbidities.

5. What consequences does late diagnosis have in girls with neurodevelopmental disorders?

A late diagnosis can lead to low self-esteem, school failure, difficulties in emotional regulation, eating disorders (ED), anxiety, depression and reduced access to appropriate educational and social supports.

6. What tools help evaluate with a gender perspective?

In addition to adapted neuropsychological tests, the use of questionnaires such as the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q) to detect camouflaging strategies, and the Social Responsiveness Scale – Second Edition (SRS-2) to assess socioemotional competencies is recommended.

7. How can NeuronUP help in personalized intervention?

NeuronUP allows designing cognitive stimulation programs adapted to each person’s profile, selecting specific activities for executive functions, attention, memory and social cognition. This facilitates bias-free interventions adjusted to the real needs of girls, women and people with diverse gender identities.

If you liked this article about neurodevelopmental disorders from a gender perspective, you will surely be interested in these NeuronUP articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Trastornos del neurodesarrollo y perspectiva de género: claves para un diagnóstico e intervención más equitativos

Personalized cognitive stimulation in people with severe mental illness: Espartales Sur Residence

Personalized cognitive stimulation in people with severe mental illness: Espartales Sur Residence

Leave a Reply