We can begin this text by agreeing, on one hand, that the most common form of onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by an early and prominent impairment of episodic memory compared to other cognitive functions and, on the other hand, that the characteristic neuropsychological profile of a patient with Alzheimer-type dementia in mild to moderate stages may include, with some interindividual variability, a combination of deficits in episodic memory, naming, alternating and divided attention, semantic categorization, working memory, verbal fluency, cognitive flexibility, monitoring and supervision, and in visuoperceptual, visuospatial and visuoconstructive skills. Assuming that with the progression of Alzheimer’s disease the impairment will affect cognition as a whole.

However, in the text we are addressing today, we will take a step back in time to focus attention on the preclinical, prodromal stages and on mild cognitive impairment (MCI), stages that are gaining increasing relevance in the field of neuropsychology due to the enormous interest, and responsibility, aroused by the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.

Biased image of Alzheimer’s disease: amnestic cognitive impairment

If we talk about Alzheimer’s disease, most people, whether they are neuropsychology professionals or not, think of amnestic cognitive impairment. This is deeply ingrained in the common imagination, and although it is true, it also reflects a biased and partial image of AD. In fact, this bias is also observed in the scientific field: most research aimed at both describing cognitive deficits and the evolutionary course of preclinical AD, prodromal stages and MCI has focused especially on the study of episodic memory (Mortamais et al., 2017).

Atypical forms of Alzheimer’s disease

But, when widening the focus of study beyond this, other “atypical” forms of AD have also been recorded and classified, which are characterized by very early predominant deficits in attention, executive functions, language or processing speed, thus increasing the accumulated evidence in favor of the phenotypic heterogeneity of AD, even in its earliest stages (Twamley et al., 2006; McKhann et al., 2011; 2010; Hassenstab et al., 2015; Han et al., 2017; Schindler et al., 2017).

The same applies to visuoperceptual and visuospatial functions which, despite being some of the least studied cognitive functions, also play a relevant role in the diagnosis and clinical course of AD. In addition, this lesser interest in the gnoses does not correspond to the impact that their alteration can have on the functional independence and quality of life of our patients. For example, visual agnosias can negatively affect a patient’s ability to properly perform activities of daily living as relevant as the ability to drive vehicles, reading and writing, recognizing familiar faces, locating products on supermarket shelves, finding an object in a drawer or a cupboard, or correctly orienting a garment to dress.

Visuospatial impairments

As I was saying, and despite the few studies that give prominence to, or at least include, visuoperceptual and visuospatial functions, evidence has been observed and accumulated indicating that some subjects show signs of visuospatial impairments such as, for example, difficulty copying a drawing, fitting pieces into two- or three-dimensional patterns, or failures on the spatial perception subtests of the Visual Object and Space Perception (VOSP) battery, even up to 5 years before an AD diagnosis, these visuospatial deficits sometimes preceding the appearance of other cognitive deficits, including the amnestic ones (Mandal et al., 2012; Schmid et al., 2013).

Visuoperceptual impairments

Something similar has been observed with visuoperceptual functions: using object visual recognition tasks such as the 15-Objects Test or the VOSP, signs of aperceptive visual agnosia have been detected in subjects who were in the preclinical and mild stages of AD (Norlund et al., 2005; Alegret et al., 2009; Quental et al., 2013).

Clinical value of visual agnosias

Along with the above, and I am not revealing anything new, we know that once a cognitive function deteriorates it will follow a progressive and irreversible course of decline. In this sense, visuoperceptual and visuospatial functions are no different, but the interesting thing is that depending on the degree of impairment in higher-level visual information processing one could discriminate and group a sample of subjects as healthy, MCI, or mild AD. That is to say, the clinical value of visual agnosias as an early diagnostic marker is added to the fact that the severity and course of their decline turns out to be a sensitive indicator of disease state and progression (Johnson et al., 2009; Alegret et al., 2009; Riley et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2011; Quental et al., 2013; Salimi et al., 2018).

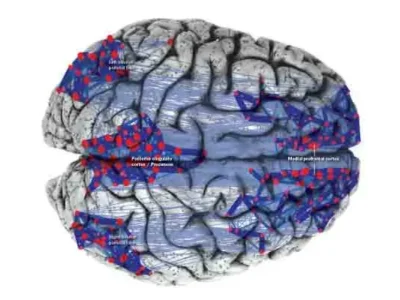

With regard to the neuroanatomical correlates of AD, in very early stages of Alzheimer’s disease there is already accumulation of beta-amyloid protein and hypometabolism in medial temporal structures such as the perirhinal cortex, entorhinal cortex and the hippocampal formation, and, even more interestingly, concurrently in regions such as the posterior cingulate cortex, the inferior parietal cortex, the precuneus and the angular gyrus, regions that are part of the posterior portion of the Default Mode Network.

Well, if we analyze these findings from the point of view of functional brain connectivity, we could expect that hypoconnectivity between the nodes that make up a medial parieto-temporal network, or the loss of connection between the dorsal and ventral pathways via the cingulate cortex, underlies the impairment in the ability to integrate and process visuospatial and visuoperceptual information in early stages of AD (Alegret et al., 2010; Schmid et al., 2013; Jacobs et al., 2015; Dubois et al., 2016; Mortamais et al., 2017).

Visual perception in Alzheimer’s disease

To focus the topic and be specific, in light of the previous data the possibility is raised that visual perception deficits may serve as a cognitive marker for the detection or diagnosis of subjects who are in the prodromal stage, and even in the preclinical stage of AD, and also to inform about the progression or worsening of the disease across its different stages.

However, we must not lose sight of the fact that the prevalence of visual perceptual deficits in patients with AD is estimated between 20% and 40%, which shows that the absence of these deficits does not mean that we are not facing a case of AD, obviously (Salimi et al., 2018).

In short, these kinds of findings force us to break old schemes and preconceived ideas about AD and adopt a broader perspective on the possible clinical expression of this disease, since it is characterized by a complex syndromic picture, in which several cognitive functions, beyond episodic memory, can play a relevant role from its onset. In fact, some even argue that if memory impairment is an indicator of AD, visuospatial deficits are a distinctive hallmark of AD, and that their use as a clinical marker could increase the specificity of the disease diagnosis (Mandal et al., 2012; Jacobson et al., 2009). But it is a possibility; only time and exhaustive examination of higher visual functions will tell.

Neuropsychological assessment

To conclude, when reviewing the available literature on AD we can conclude that it is a very heterogeneous disease, which, combined with differences inherent to each individual, forces us not to assume a priori whether there is impairment in any cognitive process.

Therefore, translated to the day-to-day of a neuropsychology clinic, this fact inevitably implies that there is no neuropsychological rehabilitation program that can be applied in a standardized, automatic or generalized way to these patients. In short, there is no mobile app, tablet app, computer program, workbook, or even a leisure or daily living task that can be recommended to all patients. Therefore, perhaps the main limitation of group neuropsychological rehabilitation sessions lies at this point.

Additionally, since the issue of AD heterogeneity is not limited to the set of signs a patient may present at a given time, a continuous adjustment of rehabilitation according to the progressive course of cognitive decline inherent to Alzheimer’s disease is also required. It may sound obvious, but it still needs to be remembered that being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease does not automatically mean being an elderly person with severe cognitive impairment and major dependence in activities of daily living.

In short, if you intend to carry out a neuropsychological rehabilitation program, there is no choice but to first conduct a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment, unravel the cognitive state of our patient process by process, intervene on them, and re-assess cognition periodically to adapt to their evolution.

References for the article ‘Visual perception in Alzheimer’s disease’

- Alegret, M., Boada-Rovira, M., Vinyes-Junqué, G., Valero, S., Espinosa, A., Hernández, I., … & Tárraga, L. (2009). Detection of visuoperceptual deficits in preclinical and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology, 31(7), 860-867.

- Alegret, M., Vinyes-Junqué, G., Boada, M., Martínez-Lage, P., Cuberas, G., Espinosa, A., … & Mauleón, A. (2010). Brain perfusion correlates of visuoperceptual deficits in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 21(2), 557-567.

- Dubois, B., Hampel, H., Feldman, H. H., Scheltens, P., Aisen, P., Andrieu, S., … & Broich, K. (2016). Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 12(3), 292-323.

- Han, S. D., Nguyen, C. P., Stricker, N. H., & Nation, D. A. (2017). Detectable neuropsychological differences in early preclinical Alz-heimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychology review, 1-21.

- Hassenstab, J., Monsell, S. E., Mock, C., Roe, C. M., Cairns, N. J., Morris, J. C., & Kukull, W. (2015). Neuropsychological Markers of Cognitive Decline in Persons With Alzheimer Disease Neuropatholo-gy. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, 74(11), 1086–1092. http://doi.org/10.1097/NEN.0000000000000254

- Jacobs, H. I., Gronenschild, E. H., Evers, E. A., Ramakers, I. H., Hofman, P. A., Backes, W. H., … & Van Boxtel, M. P. (2015). Visuospatial processing in early Alzheimer’s disease: A multimodal neuroimaging study. cortex, 64, 394-406.

- Jacobson, M. W., Delis, D. C., Peavy, G. M., Wetter, S. R., Bigler, E. D., Abildskov, T. J., … & Salmon, D. P. (2009). The emergence of cognitive discrepancies in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: A six-year case study. Neurocase, 15(4), 278-293.

- Johnson, D. K., Storandt, M., Morris, J. C., & Galvin, J. E. (2009). Longitudinal study of the transition from healthy aging to Alzheimer disease. Archives of neurology, 66(10), 1254-1259.

- Mandal, P. K., Joshi, J., & Saharan, S. (2012). Visuospatial perception: an emerging biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 31(s3), S117-S135.

- McKhann, G. M., Knopman, D. S., Chertkow, H., Hyman, B. T., Jack Jr, C. R., Kawas, C. H., … & Mohs, R. C. (2011). The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia, 7(3), 263-269.

More References

- Mortamais, M., Ash, J. A., Harrison, J., Kaye, J., Kramer, J., Ran-dolph, C., … & Ritchie, K. (2017). Detecting cognitive changes in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: A review of its feasibility. Alzhei-mer’s & Dementia, 13(4), 468-492.

- Quental, N. B. M., Brucki, S. M. D., & Bueno, O. F. A. (2013). Visuospatial function in early Alzheimer’s disease—the use of the Visual Object and Space Perception (VOSP) battery. PLoS One, 8(7), e68398.

- Salimi, S., Irish, M., Foxe, D., Hodges, J. R., Piguet, O., & Burrell, J. R. (2018). Can visuospatial measures improve the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease? Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment and Disease Monitoring, 10, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2017.10.004

- Schindler, S. E., Jasielec, M. S., Weng, H., Hassenstab, J. J., Grober, E., McCue, L. M., … & Fagan, A. M. (2017). Neuropsychological measures that detect early impairment and decline in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurobiology of aging, 56, 25-32.

- Schmid, N. S., Taylor, K. I., Foldi, N. S., Berres, M., & Monsch, A. U. (2013). Neuropsychological signs of Alzheimer’s disease 8 years prior to diagnosis. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 34(2), 537-546.

- Riley, K. P., Jicha, G. A., Davis, D., Abner, E. L., Cooper, G. E., Stiles, N., … & Schmitt, F. A. (2011). Prediction of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: longitudinal rates of change in cognition. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 25(4), 707-717.

- Twamley, E. W., Ropacki, S. A. L., & Bondi, M. W. (2006). Neuro-psychological and neuroimaging changes in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS, 12(5), 707–735. http://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617706060863

- Wilson, R. S., Leurgans, S. E., Boyle, P. A., & Bennett, D. A. (2011). Cognitive decline in prodromal Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Archives of neurology, 68(3), 351-356.

If you found this article interesting, you might also like the following articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

La percepción visual en la enfermedad de Alzheimer

Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease

Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease

Leave a Reply