Neuropsychologist Javier Esteban discusses in this article the predictive factor of dementias. Specifically, he has focused on the higher cognitive ability of language with the aim of analyzing the characteristics of its impairment in people with dementia.

The field of research on the neuropsychological profile in dementias is prolific; there is growing interest in understanding which characteristics define this nosological entity. Understanding in depth how the different cognitive abilities become affected will help us make early diagnoses in order to intervene in individuals and slow down or alleviate, as far as possible, the development and progression of the disease.

In this article we have focused on the higher cognitive ability of language with the objective of analyzing the characteristics of its impairment in people with dementia. The data indicate that language is affected in all modalities in the development of dementias, although there are some discrepancies both in the form and in the extent of the impairment.

Therefore, we are faced with a field full of possibilities for future advancement, which will allow us to be more precise in diagnosis and more accurate in intervention.

The concept of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was introduced in 1988 by Reisberg and defined within the scientific literature by Flicker and colleagues, although its interest consolidated following a study conducted by the Mayo Clinic, a renowned institution dedicated to clinical practice, education and research in the United States. Patients with MCI are at a stage between normal aging and dementia.

Moreover, statistics indicate that 50% of people with MCI will develop one of the dementias. For this reason, it is important to know the signs and symptoms that characterize these pathologies, to refine the diagnosis and establish early intervention systems that curb the progression of these diseases.

Research on language as a detector of dementias

The study of language abilities as a detector of dementias constitutes one of the most fruitful fields in the effort to specify the neuropsychological profile of the prodromal phase of dementias. The language abilities studied so far are affected to varying degrees, giving a primary role to the study of naming and phonological and semantic fluency.

At the same time, studies have begun on other linguistic dimensions that until now had not been of interest to researchers. In fact, most studies have focused on subjects’ lexical evaluation.

Gradually, paradigms such as the “tip-of-the-tongue” (TOT) are being incorporated into studies; this phenomenon implies difficulty recalling known words and is characterized by the feeling that the recollection may be imminent.

Linguistic dimensions such as the semantic and syntactic complexity of spontaneous and narrative language are also being investigated. Furthermore, in the future it will be necessary to open up new fields and analyze the relationships between language dimensions and other cognitive processes that are concurrently or secondarily altered.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Definition of the neuropsychological profile of language

When defining the neuropsychological profile of language, one must take into account four modalities: oral expression, oral comprehension, written expression and written comprehension.

Oral expression

Oral expression refers to any communication carried out by means of speech. Among the different linguistic dimensions that can be evaluated within oral expression we can point out: naming, semantic verbal fluency, phonological verbal fluency and general verbal ability.

Naming

Naming or the ability to name visual stimuli can be assessed quantitatively with tests in which the individual is asked to name, using the most precise term possible, the image that appears in a set of plates. The assessment of visual naming allows observation and quantification of a wide semiology, especially the presence of anomia and paraphasic errors, substitution of some words for others, sometimes sharing the same sound but with a different meaning, cabina instead of cabida for example.

Petersen, in separate studies in 1999 and 2009, indicates that in patients who are beginning to develop one of the dementias there is a progressive deterioration of naming abilities. In verb naming tasks there is a continuous decline, with more errors in naming, especially paraphasias. On the other hand, both age and educational level have a significant effect on performance in this type of assessment.

Semantic and phonological verbal fluency

Phonological and semantic verbal fluency is considered of great use in neuropsychological assessment because it is easy and quick to evaluate. Verbal fluency is operationalized by measuring the number of words produced within a given category that can be evoked within a limited period of time. These tests are of the type: say all the words you can that start with the letter D or any other letter, or say all the words you can within the category animals.

General verbal ability

General verbal ability consists of reasoning with verbal content, establishing among them principles of classification, ordering, relation and meaning. Also, in this parameter defects occur in discourse coherence, in the presence and maintenance of the central theme, in event repetition, in excessive use of pronouns and nonspecific referents and in false starts and internal corrections in people who are beginning to develop dementias.

To assess communication effectiveness, it would be useful to measure its fluency, naturalness, clarity, order, coherence, gesturing, articulation, content and the paralinguistic features of speech, such as volume, pitch, timbre, duration, speed, vocalizations: yawns, laughs, coughs, throat-clearing, sighs, nonverbal codes, such as; gestures, body movements, distance, timing, sweating, blushing, gaze… In fact, none of these parameters is reported in the studies that, up to Right Now, we have reviewed.

Oral comprehension

Oral comprehension is an active skill that activates a series of linguistic and non-linguistic mechanisms. It involves developing the ability to listen to understand what others say. In addition, to assess this skill, the tests used would consist of administering oral commands and transmitting stories after which comprehension would be evaluated through questions. People who are beginning to develop dementia have more difficulty correctly understanding irony and generally perform worse on all tests that evaluate oral comprehension.

Written expression

Written expression consists of expressing any thought or idea by means of conventional signs and in an orderly manner. It can be evaluated through a variant of oral semantic and phonological naming tests; in this case the assessment is carried out through a pencil-and-paper test with a semantic and phonological key. The results of studies on this dimension of language show that people who are beginning to develop dementia write fewer correct words under phonological evocation criteria; the same occurs with semantic evocation criteria, and they also produce more perseverations. In short, there is a progressive deterioration of writing abilities.

Written comprehension

Written comprehension is the ability to understand what is read, both with respect to the meaning of the words that make up a text and regarding the global understanding of a written passage. The tests used to assess this dimension consist of lexical decision tasks, in which after reading a text decisions must be made about what the text asks of us, allowing us to evaluate whether it has been understood; also tests of word identification and reading aloud.

Indeed, in people who begin to develop dementia there is evidence of impairment in the processing of written language comprehension that makes it more difficult to understand lexical stimuli and that begins to emerge early in the initial stages of the disease.

Moreover, in sentence recognition poorer performance is observed in all types of sentences in people who are beginning to develop one of the dementias. In addition, variability increases as impairment increases in the case of nouns and in one-clause sentences that do not follow syntactic order.

On the other hand, it is noted that written comprehension begins a continuous deterioration with statistically significant differences in reading aloud tests and in sentence and paragraph comprehension performance between people with normal aging and people who are beginning to develop dementia.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the data available from research on the neuropsychological profile of the cognitive ability of language in dementias indicate that it is still not entirely clear whether the naming deficit is due to difficulty accessing the phonological content rather than the semantic content of the concept. It is argued that a semantic representation of the word is produced but the transmitting impulse to the phonological representation is missing, since the individuals evaluated in one of the studies were able to describe characteristics of the word they wanted to name but were not able to name it.

Oral expression as a predictor of dementias

What we can conclude is that naming tasks are good predictors of clinical groups that are beginning to develop dementias compared to healthy individuals, as numerous studies indicate. (Petersen et al, 1999; Facal et al 2009; Carballo et al, 2015, Rodriguez, Facal and Juncos-Rabadán, 2008; and Hubner et al, 2017), taking into account that both educational level and age produce different results in naming evaluation.

In addition, phonological and semantic fluency appear to have a quite precise discriminative value (Facal et al, 2009 and Carballo et al, 2015.)

General verbal ability is impaired with respect to expression in various aspects studied through discourse elicitation (Diggle et al, 2016 and Alonso-Sánchez et al 2018).

Oral comprehension as a predictor of dementias

Oral comprehension also seems to be compromised in the development of dementias, although we find contradictory results. Gaudreau et al, 2013 and Carballo et al, 2015, report comprehension impairment, but Facal et al, 2009, indicate that comprehension is not altered. Sometimes we do not understand, not because we do not grasp the words our interlocutor has uttered, but because we do not know the context. For this reason, the structuring of this type of test should be reconsidered.

Written expression as a predictor of dementias

In written expression, healthy groups evoke more words under both phonological and semantic criteria; there are also differences in the encoding of the different words evoked (Ruiz Sánchez de León et al, 2011; Carballo et al, 2015. Werner et al, 2006). Therefore, it would be worthwhile to focus on the study of evolution in written expression, in the sense of determining what types of constructions can be used to discriminate between individuals with cognitive impairment and healthy ones.

In addition, we could assess the morphological use of words, the use of syntax, spelling errors, errors of gender, number… Characterize these tests with deeper content than the mere count of words evoked.

Written comprehension as a predictor of dementias

Written comprehension has also been found to be impaired in patients developing dementia (López-Higes et al, 2010. López-Higes et al, 2014. Hernández and Amórtegui, 2016. Carballo et al, 2015). Consequently, we could introduce different forms in this type of tests to locate which kinds of sentences are more difficult to determine or which are more sensitive to deterioration, among declarative, positive or negative, interrogative, exclamatory, hortative, conditional, future…

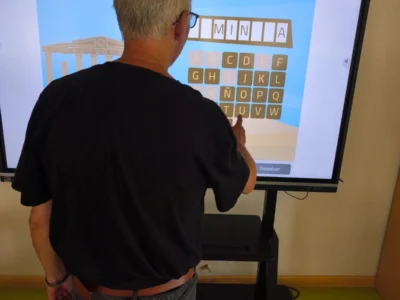

The importance of studying the neuropsychological profile of language in dementias lies in implementing precise diagnostic procedures and therefore initiating techniques of early intervention for this ability, adapting training to the different dimensions that comprise human language. In fact, the cognitive stimulation of this ability is a necessary and very useful tool to alleviate the deterioration of this aptitude that gives us the competence to make ourselves understood and to understand others’ discourse, which promotes autonomy and independence. Moreover, through the tools of cognitive stimulation and neurorehabilitation we must train, exercise, maintain and preserve language for as long as possible and with the greatest skill, expertise and ease possible in people diagnosed with dementia since it will result in greater well-being and adaptation for these individuals.

Bibliography

- Artero, S., Petersen, R., Touchon, J. and Ritchie, K. (2006). Revised criteria for mild cognitive impairment: validation with a longitudinal population study. Dementia. Geriatric and cognitive disorders, 22, 465-470.

- Carballo, G., García-Retamero, R., Imedio, A. and García-Hernández, A. (2015). Diagnosis of cognitive impairment onset in older adults based on limitations in language skills. Studies in Psychology, 36, 316-342.

- Croot, K., Hodges, J.R. and Patterson. (1999). Evidence for impaired sentence comprehension in early Alzheimer´s disease. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 5, 383-404.

- Diggle, K., Koscik, R., Turkstra, L., Riedeman, S., Larue, A., Clark, L., Hermann, B. and Sager, (2016). Connected Language in late middle-aged adults at risk for Alzheimer´s disease. Journal of Alzheimer´s disease, 54, 1539-1550

- Facal, D., Gonzalez, M., Buiza, C., Laskibar, I., Urdaneta, E. and Yanguas, J. (2009). Aging, cognitive impairment and language: results of the Donostia longitudinal study. Revista de logopedia, foniatría y audiología 29, 4-12.

- Fernández, M., Ruiz, J., Lopez, J., Llanero, M., Montenegro, M. and Montejo, P. (2012). New shortened version of the Boston Naming Test for people over 65 years: an approach from item response theory. Neurol 55, 399-407.

- Ferreira, D., Correia, R., Nieto, A., Machado, A., Molina, Y. and Barroso, J. (2015). Cognitive decline before the age of 50 can be detected with sensitive cognitive measures.

- Psicothema ,27. P 226-222 Flicker, C., Ferris, S. H. and Reisberg, B. (1991). Mild cognitive impairment in the elderly predictions of dementia. Neurology, 41, 1006-1009.

- Gaudreau, G., Monetta, L., Poulin, S., Laforce, R. and Hudon, C. (2013). Verbal irony comprehension in older adults with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology, 27, 702-712

- Hernández, J. and Amortegui, D. (2016). Processing of words with emotional content in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Acta Neurológica Colombiana, 32(2), 115-121.

- Juncos-Rabadán, O., Rodriguez, N., Facal, D., Cuba, J. and Pereiro, A. (2011). Tip of the tongue for proper names in mild cognitive impairment. Semantic or post-semantic impairments?. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 24, 636-651.

- Juncos-Rabadán, O., Pereiro, A., Facal, D. and Rodriguez, N. (2009). A review of research on language in mild cognitive impairment. Revista de Logopedia, Foniatría y audiología, 30-2, 73-83

- Juncos-Rabadán, O., Facal, D., Álvarez, M. and Rodriguez, M. (2006). The tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon in the aging process. Psicothema, 18, 501-506.

- Juncos-Rabadán, O., Pereiro, A., Alvarez, M. and Facal, D. (2006). Variability in lexical access in normal aging. Revista de Logopedia, Foniatría y audiología, 26, 132-138.

- Lezak, M. D. (1995). Neuropsychological assessment. 3 ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lopez-Higes, R., Prados, J.M., Montejo, P., Montenegro, M. and Lozano, M., (2014). Is there a grammatical comprehension deficit in multidomain mild cognitive impairment. Universitas Psychologica, 13(4), 1569-1579.

- Lopez-Higes, R., Rubio, S., Martín, A. and del Rio, D. (2010). Interindividual variability in vocabulary, sentence comprehension and working memory in the elderly: effects of cognitive deterioration. The Spanish journal of Psychology, 13, 75-87.

- Lopez-Higes, R., Rubio, S., Aragoneses, M. and del Rio, D. (2008). Variability in grammatical comprehension in normal aging. Revista de Logopedía, foniatría y audiología, 28, 15-27.

- Macoir, J., Lafay, A. and Hudon, C. (2018). Reduced lexical access to verbs in individuals with subjective cognitive decline. American Journal of Alzheimer´s Disease and other Dementias XX (X). DOI:10.1177/1533317518790541

- Petersen, R. and Morris, J. (2003). Mild cognitive impairment. New York: Oxford University press. Petersen, R. C., Smith, G., Waring, S., Ivnik, R., Tangalos, E. and Kokimmen, E. (1999). Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Archives of neurology, 56, 303-308.

- Ruiz Sanchez de León, J.M., Moratilla, P. and Llanero, M. (2011). Written verbal fluency in normal aging with subjective memory complaints and in mild cognitive impairment. Anales de Psicología, 27, 360-368.

- Rodriguez, N., Juncos-Rabadan, O. and Facal, D. (2008). The tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon in mild cognitive impairment. A pilot study. Revista de logopedia, foniatría y audiología, 28, 28-33.

- Subirana, J., Bruna, O., Puyuelo, M. and Virgili, C. (2009). Language and executive functions in the initial assessment of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer-type dementia. Revista de logopedia, foniatría y audiología, 29. P. 13-20.

- Taler, V. and Phillips, N. A. (2008). Language performance in Alzheimer´s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A comparative review. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 30, p. 501-556

- Vendrell, J.M. (2001). Aphasias: semiology and clinical types. Neurology, 32, p. 980-986 Werner, P., Rosenblum, S., Bar-On, G., Heinik, J. and Dorczyn, A. (2006). Handwriting process variables discriminating Mild Alzheimer´s Disease and Mild cognitive impairment. The journals of gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and social sciences, 61, p. 228-236

If you liked this post about language as a predictor of dementias, we recommend you take a look at these NeuronUP publications:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

El lenguaje como factor predictor de las demencias

Language Session for People with Mild Cognitive Impairment

Language Session for People with Mild Cognitive Impairment

Leave a Reply