Neuropsychology occupies a prominent place among the sciences related to education. According to Portellano (2014) it not only helps diagnosis but also the rehabilitation and enhancement of the cognitive and emotional functions. Therefore, it is very important to take into account the neuropsychological development and the maturity of executive functions in our students to influence how to design the most effective methodologies and activities that contribute to their holistic development, especially in students with special educational needs.

Definition and characteristics of executive functions

Numerous authors have investigated executive functions. Luria (1974) was the first neurologist to speak of the system; however, the first definition is attributed to Lezak (1982) who states that executive functions are the mental capacities essential to carry out effective, creative and socially acceptable behavior.

Later, it was Stuss (2010) who defined them as the skills controlled by the prefrontal cortex. These functions allow planning and keeping goals in working memory. They also allow selecting actions or appropriate behaviors to orient them toward the achievement of those goals.

Currently executive functions are considered the set of activities that take place in the prefrontal area. In this way, they construct the essence of our behavior and of all mental activity, constituting the human central processor. Likewise, they are responsible for solving problems that require reasoning, abstraction or the use of symbolic codes (Portellano et al. 2009).

Levels of intelligence in the study of executive functions

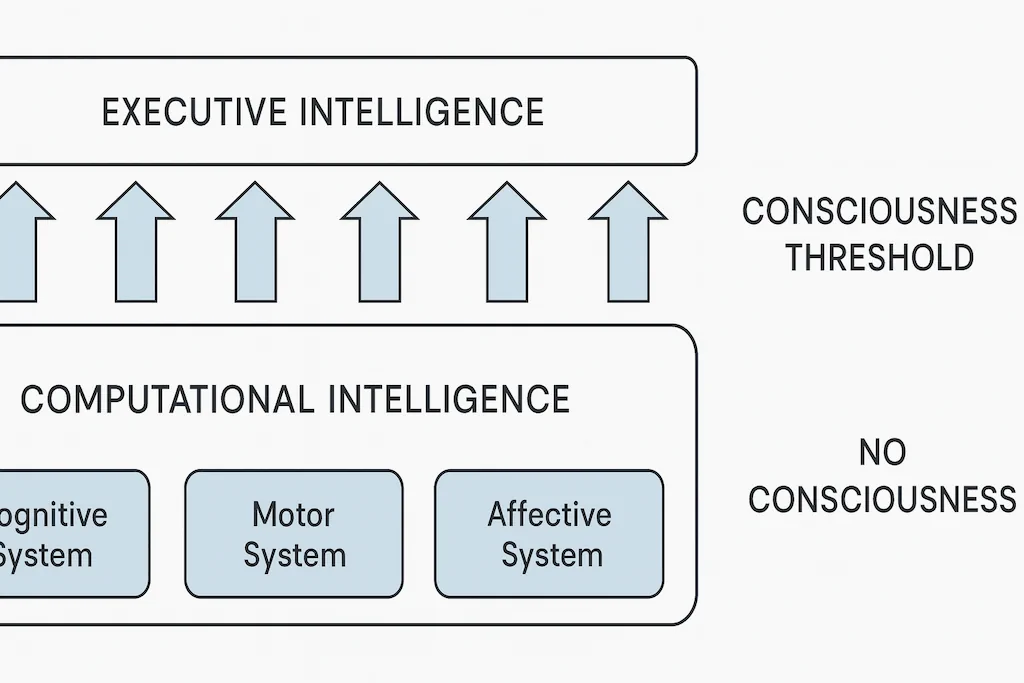

Indeed, authors such as Marina (2013) distinguish two levels of intelligence in the study of executive functions. First, a productive or computational intelligence that is considered the origin of our conscious activity. Finally, an executive intelligence which supervises, evaluates and directs attention, as can be seen in Figure 1.

With all this, according to Goleman (2013) and Marina (2013), the concept of executive intelligence arises as the one that directs mental and physical action by making use of knowledge and emotions, being considered a possible additional indicator to evaluate academic and professional performance.

Components of executive functions

Clearly there is a wide variety of definitions. We also find different classifications of their components.

Self-control, working memory and cognitive flexibility

According to Knapp and Bruce (2013) executive functions can be classified into three categories of skills. First, self-control which is the ability that helps students pay attention and control impulsivity by avoiding interference. Finally, working memory and cognitive flexibility, which include creative thinking and the ability to adapt to changes, helping students channel their imagination and creativity for problem solving. However, for Moraine (2014) their components are memory, organizational capacity and attention

Reasoning, problem solving and planning

Also, Bagetta and Alexander (2016) propose three basic components for success in a student’s academic performance and personal well-being. These components are directly related to each other and allow the development of other complex functions such as reasoning, problem solving or planning.

Mental flexibility, verbal fluency, attentional regulation, operative or working memory and inhibitory control

Finally, and according to Portellano et al. 2009, a review of executive functions that are directly related to learning and consequently to academic performance, includes the following components:

- Mental flexibility: since it allows adapting responses to new situations or stimuli. Therefore, new behavior patterns are generated offering diverse alternatives. Likewise, this implies a quick analysis of the situation and an agile working memory that enables offering alternative responses.

- Verbal fluency: it is related to mental flexibility, as it allows responding quickly and accurately. It is usually measured with phonological and semantic verbal fluency tests.

- Attentional regulation: allows all cognitive processes to be carried out. Consequently, it provides a person with better selective and sustained attention and mastery of the ability to inhibit and control behavior (Anderson and Jacobs, 2002).

- Operative or working memory: a form of short-term memory that provides temporary storage of information. It also allows the learning of new tasks.

- Inhibitory control: regulates or delays impulsive responses by shaping behavior and attention as a catalyst for information processing in cognitive processes. Clearly, good inhibitory control appears when the student is able to maintain attention on the task they are performing without getting distracted.

Development of executive functions

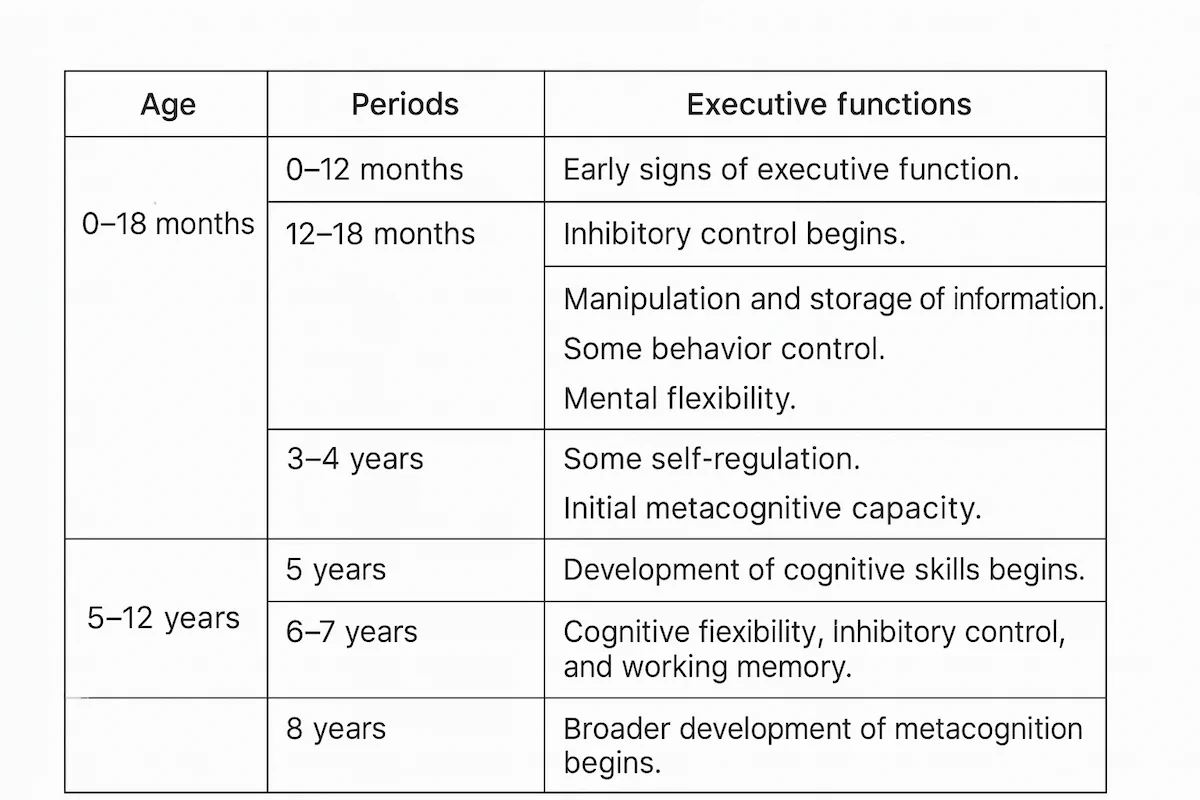

Executive functions have several sensitive periods of maturation, the ones most related to the stages of early childhood and primary education, that is, those between 2 and 5 years and between 11 and 12 years, progressing slowly in their evolution (Tirapu and Luna, 2008).

Adapted from Tirapu and Luna (2008)

Neuropsychological bases of executive functions

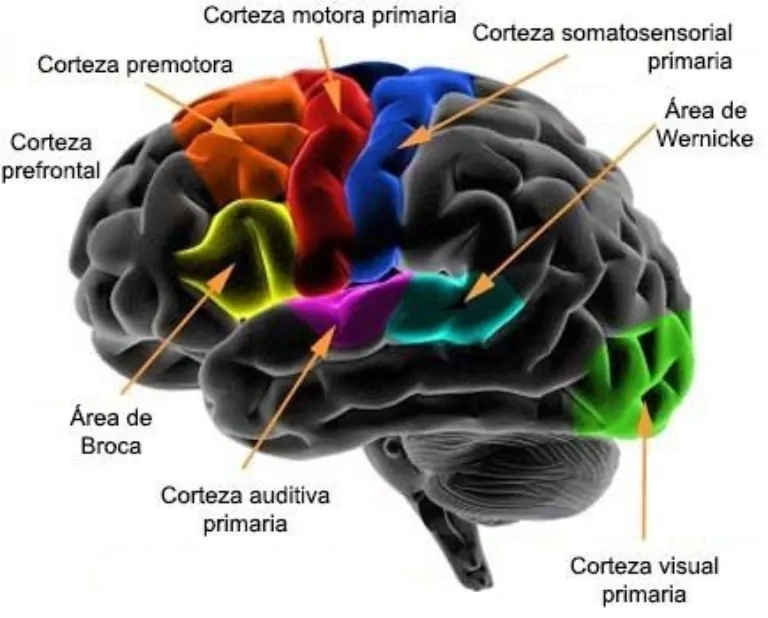

Executive functions are located in the frontal lobe which is divided into two functional zones. It is also responsible for supervising the activity of brain areas by programming and regulating all cognitive processes. These functional zones are the motor cortex and the prefrontal area.

Motor cortex

It is responsible for designing and planning voluntary motor activities. It is also responsible for sequencing and executing intentional movements including those necessary for expressive language and writing (Figure 2). Likewise, it is divided into three different areas: the primary motor area, the premotor cortex and Broca’s area.

Prefrontal area

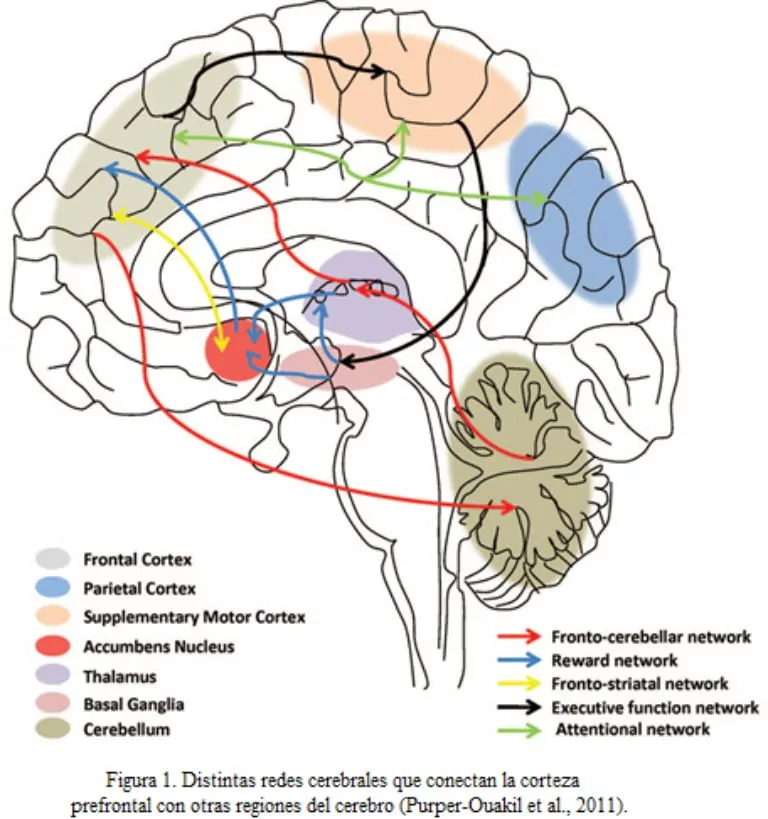

According to Portellano et al. (2009) its main function is executive functioning which allows programming, developing, sequencing, executing and supervising any planning or behavior directed toward goal achievement, decision-making and attention control. For this reason, it is the most important area in the study of executive functions. In addition, it is located in the frontal lobe of the brain. Therefore, this extensive network of executive functions is fundamentally found in the prefrontal cortex.

Indeed, it is the brain area best connected in the brain as can be seen in Figure 3. Also, according to Diamond and Ling (2016) it is the most modern region of the brain, but also the most vulnerable, since stress, sadness, loneliness or a poor physical condition can impair its proper functioning.

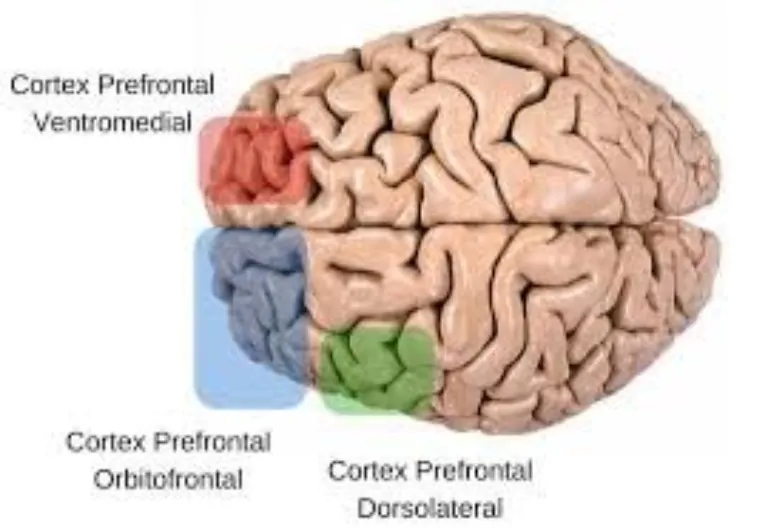

Similarly, according to Portellano et al. (2011) the prefrontal area is the highest expression of human intelligence because it coordinates cognitive processes and programs behavior to achieve effective decision-making. In this zone three functional areas are distinguished (Figure 4):

- Dorsolateral area: it is located on the outer zone of the frontal lobe under the frontal bone. It is also the zone of the prefrontal cortex that is most activated when performing higher complexity mental activities (Portellano et al., 2009).

- Cingulate area: it is located on the inner faces of the prefrontal areas, over the anterior half of the cingulum bundle. It is also an area of special relevance in intentional processes that require human will, especially in language.

- Orbital area: it is located at the base of both frontal lobes above the eye orbits. It is also closely related to emotional processes due to its close connections with the limbic system.

Definition and characteristics of the reading process

Reading is fundamental in the teaching-learning process and essential for linguistic and intellectual development. Clearly, reading is a complex process for humans and is not a homogeneous and single ability, but rather comprises a set of skills that depend on the development of executive functions.

In our educational system, Royal Decree 126/2014 which establishes the basic curriculum of Primary Education, reading and reading comprehension are instruments that enable the acquisition of knowledge in the various areas and the development of all competences. Likewise, reading can be performed by two independent routes: the indirect or phonological route and the direct or lexical route.

Neuropsychological bases of the reading process

The human brain is not endowed with pre-established neural networks for reading. Consequently, it is a skill that requires learning to associate graphic symbols (vision), sounds (hearing) and meanings (semantic memory).

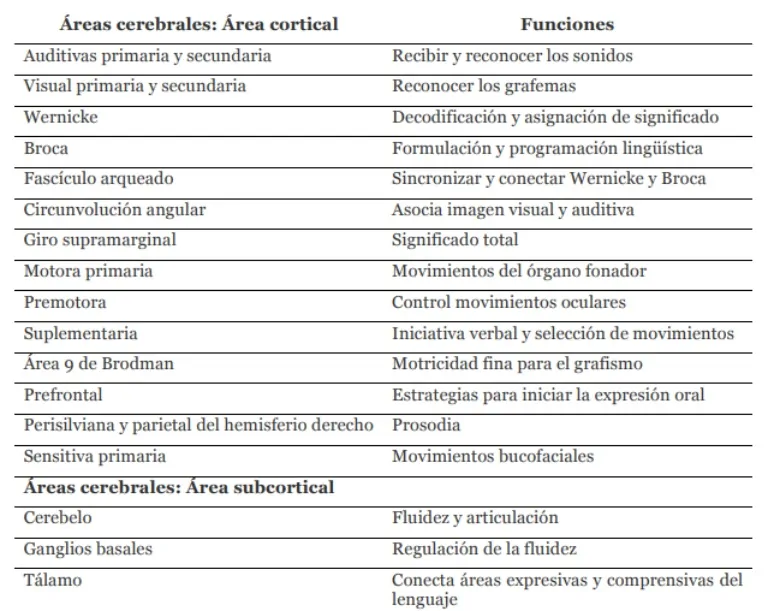

The mental representations of these three contents are carried out in specific networks, so reading would imply the creation of new connections between circuits of these networks in which executive functions directly influence. In Table 2, according to De la Peña (2016), the brain areas involved in reading and their functions can be seen.

Functional circuits of the reading process

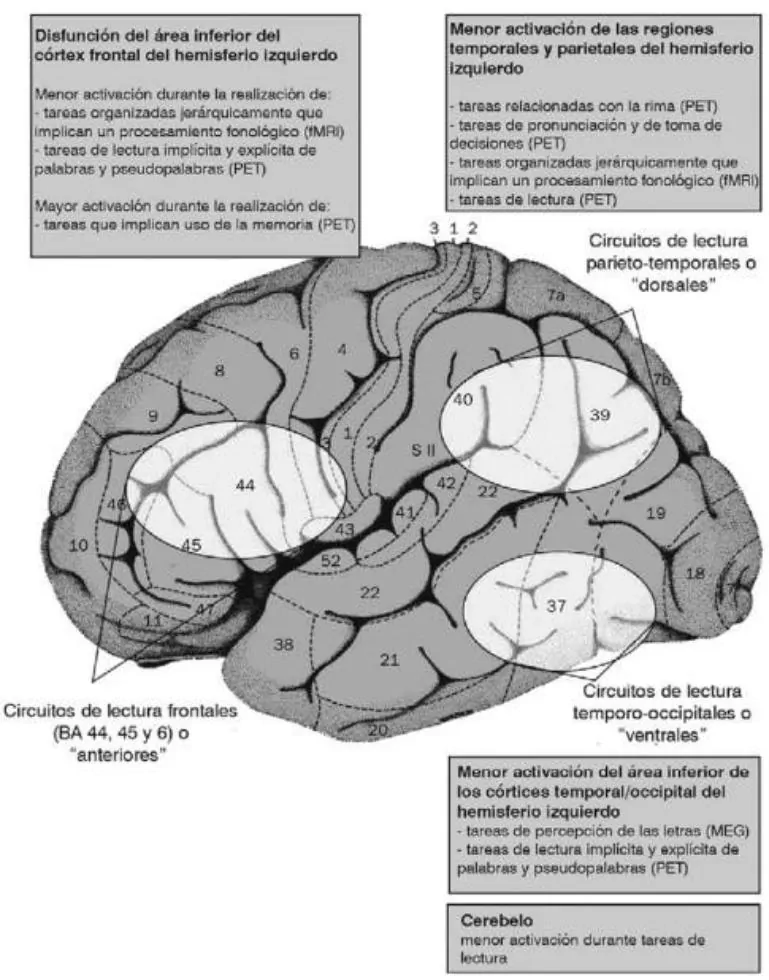

According to De la Peña (2012) neuroimaging techniques have revealed the existence of three functional circuits involved in the reading process. These circuits are: the dorsal, the ventral and the anterior frontal.

First, the ventral circuit would begin with the entry of information through the primary and secondary visual areas in the occipital lobe. Therefore, it facilitates the global processing of words. Subsequently, it would pass to the angular gyrus and Wernicke’s area, which would allow decoding, that is, the grapheme-phoneme correspondence and comprehension. Later, it would pass to the arcuate fasciculus to reach Broca, which is responsible for the formulation of the phonetic sequence. Finally, it would end in the motor areas that would perform the movement of the buccofacial praxias.

In Figure 6 we can see these reading circuits. One can also observe the brain areas in which functional abnormalities have been detected in subjects with difficulties in the reading process. Therefore, a personalized intervention for the maturation of executive functions is recommended (Benitez-Burraco, 2007).

Academic performance

According to Navarro (2003) academic performance is the system that measures achievements and the construction of knowledge in students. These are created by the intervention of educational didactics that are evaluated through quantitative and qualitative methods in a subject.

Likewise, Figueroa (2004) expresses its measurement in grades within a conventional scale from 0 to 10. Although its objectivity lies in the fact of evaluating knowledge expressed in grades, academic performance is the result of multiple factors, both environmental and personal. As a result of the different stages of the educational process and the transformations undergone by the student, these factors affect each one variably.

Relationship between executive functions, the reading process and academic performance

According to Bernal (2005) what is learned is recorded in the brain and forms memory, since memory is an executive function that allows recording, encoding and consolidating. It also allows retaining, storing, retrieving and evoking previously stored information according to Portellano (2005). That is why it is the protagonist of all higher cognitive processes.

Moreover, a limited capacity in memory processes leads to limited academic performance in arithmetic calculation (Alsina, 2001) and in reading (Baqués and Sáiz, 1999). Likewise, reading processes and especially reading comprehension are the result of encoding and manipulating information. Still, all this involves cognitive tasks supported by executive functions, especially working memory capacity (García-Madruga and Fernández-Corte, 2008). Authors such as Melzter and Krishnan (2007) argue that executive functions are indispensable for achieving school goals because they coordinate basic and higher cognitive processes.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of a neuropsychological intervention in the classroom means that students discover techniques and strategies like those offered by NeuronUP. Likewise, these techniques help them carry out their learning more appropriately and overcome the difficulties of neurodevelopmental disorders (ADHD, Dyslexia, Dyscalculia, SLI, among others).

As a result, the fundamental basis is to work on executive functions, since it can be carried out in the classroom without altering the normal course of lessons. Likewise, it contributes in a playful and motivating way to the classroom environment and to the holistic development of students.

It is also worth highlighting the importance of professionals developing a spirit of openness and ongoing training. Therefore, this contributes to their professional development effectively and to the right of students to receive an education adjusted to their needs.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Bibliography

- Anderson, P. (2002). Assessment and development of executive function (EF) during childhood. Child Neuropsychology, 8, 71-82.

- Alsina, R. (2009). Models of communication in the European Higher Education Area. The case of Pompeu Fabra University. Revista Académica de la Federación Latinoamericana de facultades de comunicación social, 78. Retrieved from: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/3719761.pdf

- Baggetta P., Alexander P. A. (2016): Conceptualization and Operationalization of Executive Function. Mind, Brain, and Education 10 (1), 10-33. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12100

- Baqués, J. y Sáiz, D. (1999). Simple and composite measures of working memory and their relationship with the learning of reading. Psicothema, 11(4), 737-745. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/28113166_Medidas_simples_y_compuestas_de_ memoria_de_trabajo_y_su_relacion_con_el_aprendizaje_de_la_lectura

- Bernal, I.M. (2005). Psychobiology of learning and memory. CIC Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación, 10 221-233. Retrieved from: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/935/93501010.pdf

- Buller, I., (2010). Effective Neuropsychological Assessment of Executive Function. Proposal for a compilation of neuropsychological tests for the assessment of executive functioning. Cuadernos de Neuropsicología/Panamerican Journal of Neuropsychology, 4, 1, 63. Retrieved from: http://biblioteca.unir.net/documento/evaluacion-neuropsicologica-efectiva-de-la-funcion- ejecutiva-propuesta-de-compil/FETCH- doaj_primary_oai_doaj_org_article_3e158867f6854c36bc140171b579aea93

- De la Peña, C. (2012). Dyslexia from child neuropsychology. Madrid. Editorial Sanz y Torres.

More references

- De la Peña, C. (2016). Programs for Dyslexia from the neuropsychological basis. In P. Martín- Lobo, (Coord.). Processes and programs of educational neuropsychology. Madrid. CNIIE.

- Diamond, A. and Ling, D. (2016). Conclusions about interventions, programs, and approaches for improving executive functions that appear justified and those that, despite much hype, do not. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 18, 34-48.

- García-Madruga, J.A. and Fernández-Corte, T. (2008). Operative memory, reading comprehension and reasoning in secondary education. Anuario de Psicología, 39(1), 133-157. Retrieved from: https://www.raco.cat/index.php/AnuarioPsicologia/article/download/99799/159769

- Goleman, D. (2013). Focus. Barcelona. Kairós.

- Knapp, F. and Morton, B. (2013). The development of the brain and executive functions. Encyclopedia on early childhood development. Retrieved from: http://www.enciclopedia- infantes.com/sites/default/files/dossiers-complets/es/funciones-ejecutivas.pdf

- Lezak, M.D. (1982). The problem of assessing executive functions. International Journal of Psychology, 17(2-3), 281-297. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00207598208247445

- Luria, A.R. (1974). Foundations of neuropsychology. Barcelona. Fontanella. Retrieved from: https://www.raco.cat/index.php/anuariopsicologia/article/viewFile/64539/88470

Additional bibliography

- Marina, J.A. (2013). The new model of intelligence. Retrieved from: http://www.joseantoniomarina.net/articulo/1537/

- Meltzer, L., & Krishnan, K. (2007). Executive Function Difficulties and Learning Disabilities: Understandings and Misunderstandings, 77-105. New York. Guilford Press. Retrieved from: http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-03950-005

- Moraine, P. (2014). The student’s executive functions: Improving attention, memory, organization and other functions to facilitate learning. Madrid. Narcea.

- Portellano, J. A., Martínez, R. and Zumárraga, L. (2009). ENFEN: Neuropsychological Assessment of executive functions in children. Madrid: TEA ediciones.

- Portellano, J.A., and García, J. (2014). Neuropsychology of attention, executive functions and memory. Madrid. Síntesis.

- Royal Decree 126/2014, of 28 February, which establishes the basic curriculum of Primary Education. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 52, of 1 March 2014.

- Stuss, D.T. (2010). Is there a dysexecutive syndrome? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Biological Sciences (362) 901-915. Retrieved from: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/727/72712496009.pdf

- Tirapu, J., and Luna, P. (2008). Neuropsychology of executive functions. Manual of neuropsychology. Barcelona: Viguera Editores, SL, 221-256.

If you liked this blog post about executive functions and their relationship with learning processes, you may also be interested in

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Las funciones ejecutivas y su relación con el proceso lector y el rendimiento académico

What is the role of a Down Syndrome Association? The Down Navarra case

What is the role of a Down Syndrome Association? The Down Navarra case

Leave a Reply