Neuropsychologist Salus Corpas Molina presents the most common mistakes when starting clinical practice in neuropsychology and how they can be avoided.

Introduction

Starting to work as a clinical neuropsychologist often involves a mix of enthusiasm and insecurity. Suddenly, we leave the orderly cases from manuals and face patients with brain injury, neurodegenerative diseases, psychiatric disorders and overwhelmed families. In that context, it is common to make some mistakes at the beginning that can wear down the professional and reduce the impact of the intervention. The following lines review some of the most common errors when starting in clinical neuropsychology and propose concrete ways to avoid them.

10 most common mistakes when starting clinical practice in neuropsychology

1. Using fixed test batteries in neuropsychological assessment instead of clinical reasoning

One of the first pitfalls is thinking that doing neuropsychology means always applying the same battery to everyone. At the beginning, the professional may feel more secure with a closed protocol, but a rigid battery usually unnecessarily prolongs the assessment, tires the patient and generates data that are of little relevance to real clinical practice. The American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (AACN) guidelines remind us that the assessment should be flexible and hypothesis-driven, not habitual (AACN, 2007).

The change of approach involves addressing each case from a well-defined question: what needs to be answered and for whom. It is not the same to assess whether a person is fit to return to work as it is to distinguish between depression and neurodegenerative decline. From that referral, hypotheses are formulated (for example, suspicion of a dysexecutive syndrome after a traumatic brain injury) and a limited set of truly informative tests are selected, combining exploration of basic domains with more specific tests (Cicerone et al., 2000). The key is that tests are chosen based on the case, not the other way around.

2. Interpreting scores without linking the cognitive profile to the patient’s daily life

Another common error in clinical neuropsychology practice is getting stuck on scores. The report ends up becoming a succession of percentiles and standard deviations, while the patient’s real life barely appears. However, rehabilitation literature emphasizes that the focus should be on function and participation, that is, on what the person can or cannot do in their context (Cappa et al., 2005; Cicerone et al., 2019; Ramos-Galarza & Obregón, 2025).

To avoid this disconnection, the clinical and functional history must occupy a central place. It matters to know how the patient was before, what has changed, which tasks have become impossible or very slow, which responsibilities they have had to delegate. From there, scores are read as a language that translates those difficulties: a deficit in verbal episodic memory stops being a number and is concretely expressed as not remembering medication doses or repeating the same questions, which has direct implications for safety, autonomy and caregiver burden. Including functioning questionnaires based on the International Classification of Functioning (ICF) helps anchor the cognitive profile to everyday reality (Cicerone et al., 2019).

3. Underestimating the emotional and psychiatric dimension in clinical neuropsychological practice

Many patients come to consultation with a combination of factors: brain injury, anxious-depressive symptoms, chronic pain, sleep problems, family conflicts. It is easy to fall into two simplifications: attribute everything to “the neurological” or, conversely, reduce it to “it’s anxiety”. More integrative models of neurorehabilitation point out that an effective intervention combines cognitive work and emotional approach, understanding the patient as an integrated whole, in which there is a dynamic interconnection between biological, psychological, social and environmental aspects (García-Molina & Prigatano, 2022; Cicerone et al., 2011; Ramos-Galarza & Obregón, 2025).

In clinical practice it is advisable to systematically incorporate some measure of depression, anxiety or post-traumatic stress, observe variability of effort during sessions, and review medical variables such as pain, fatigue or pharmacological side effects. Unstable performance, marked task avoidance or hypersensitivity to error may signal that emotional distress is interfering. Coordinating with psychiatry and clinical psychology allows psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments to act as enhancers of cognitive rehabilitation (Ramos-Galarza & Obregón, 2025).

4. Making hasty neuropsychological diagnoses and overinterpreting tests

When starting out, there is a temptation to give quick, categorical answers: “it’s ADHD”, “it’s dementia”, “there are no sequelae”; the risk lies in overemphasizing an isolated test and forgetting basic aspects of interpretation, such as reliability, validity and the false positive rate. If many tests are applied, it is to be expected that some of them will score low even in healthy people, something the AACN (2007) explicitly emphasizes.

Work by Cicerone and colleagues insists on always reading patterns of performance, not isolated items (Cicerone et al., 2005, 2011). It is important to check whether several tasks that demand the same process fail convergently, whether performance fits the clinical history and behavioral observation, and whether there are factors that explain atypical findings (fatigue, low educational level, language, motivation). Also, in evolving processes such as mild cognitive impairment, diagnostic prudence and longitudinal follow-up are often more useful than a quick label (Cicerone et al., 2011, 2019).

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

5. Writing lengthy neuropsychological reports that are of little use for intervention

The neuropsychological report is one of the main communication tools with the team and the family. However, a common mistake is turning it into a very long document, with many tables and technical terminology, but not actionable. In this case, the reader may end up with the feeling that many results have been generated from the tests without understanding what to do with the information.

For the report to be truly clinical:

- It is advisable to open with a brief initial summary indicating the reason for referral, the essential qualitative and quantitative findings, and the main conclusions (AACN, 2007).

- In the body of the text, scores can be grouped by domains, indicating whether performance is appropriate for age and education, and linking each result with functional consequences in activities of daily living: managing medication, driving, handling money, home safety, etc.

- Recommendations should be presented in a prioritized manner, indicating what requires immediate intervention, what should be monitored and what referrals are advisable (Cicerone et al., 2000, 2019).

- A good rule of thumb is that any team professional, after reading two pages, should be able to answer the question: “and right now, what do we do?”.

6. Designing cognitive rehabilitation programs based only on exercises

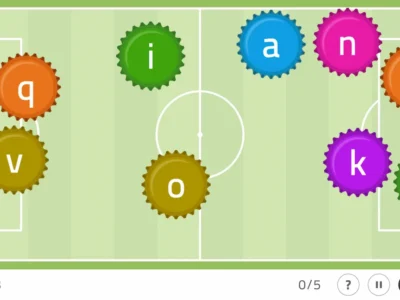

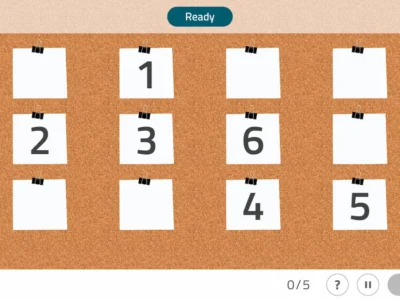

Another classic trap is reducing rehabilitation to a set of digital worksheets or exercises. It may look like a lot of work from the outside, but if there are no clearly defined goals and generalizable strategies, improvements remain confined to the task. Reviews on cognitive rehabilitation show better results when training of specific processes is combined with compensatory strategies and clear functional goals (Cicerone et al., 2000, 2005, 2011, 2019; Cappa et al., 2005).

This implies formulating goals such as “in eight weeks, the person will be able to independently organize two medical appointments per month” and designing sessions that work attention, memory or executive functions in service of that goal. Paper-and-pencil exercises, software programs or digital platforms can be used, but always connected to activities meaningful to the person: preparing shopping, managing a calendar, handling money in simulated situations. At the same time, external aids are introduced (alarms, visual agendas, home organization systems) and it is periodically reviewed whether these changes translate into observable improvements in daily life (Cicerone et al., 2019; Ramos-Galarza & Obregón, 2025).

7. Working in isolation instead of integrating into the neurorehabilitation team

In many settings, the neuropsychologist begins occupying a kind of peripheral role: they are called in “to give tests” when a report is needed. This isolated position favors errors both from overload and lack of coordination. European guidelines on cognitive rehabilitation emphasize that neuropsychology must be fully integrated into neurorehabilitation programs, sharing goals with neurology, physiotherapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy and social work, since work in one area benefits the rest (Cappa et al., 2005; Cicerone et al., 2011).

In daily practice this means participating in clinical meetings, proposing transversal goals (for example, working on attention and dual-tasking during gait sessions), agreeing on behavioral management or communication strategies with the family and using common follow-up indicators. In this way the neuropsychologist stops being “the test person” and becomes a link between the cognitive profile and the interventions of the rest of the team, which increases both therapeutic effectiveness and professional visibility.

8. Not incorporating clinical guidelines and updated literature in neuropsychology

It is understandable that in the first years more weight is given to “what is done in my center” or “what they taught me in the master’s program”. The problem arises when that practice is not contrasted with the guidelines and reviews that have been published. Today we have reference documents for both assessment and rehabilitation that should be known at least generally (AACN, 2007; Cappa et al., 2005; Cicerone et al., 2000, 2005, 2011, 2019; García-Molina & Prigatano, 2022; Ramos-Galarza & Obregón, 2025; Ramos-Galarza & Gaibor, 2025).

A reasonable habit is to reserve, for example, one hour a month to review a review article or a clinical guideline and ask whether any specific recommendation can be applied to one’s own work context. Sharing readings within the team also helps, so protocol change decisions do not depend on a single person. This periodic updating is not about following trends, but about recalibrating practice and preventing routines from drifting away from what works best according to the available evidence.

9. Not respecting ethical limits and professional competence in neuropsychology

Accepting all cases that come in may seem, at first, a moral obligation or a way to demonstrate competence. However, taking on complex forensic cases, assessments in languages the professional does not master, or clinical profiles—common and more exceptional—for which one does not yet have sufficient experience, without supervision, can pose a risk both to the patient and to the neuropsychologist. AACN guidelines remind us of the importance of working within one’s limits of competence and of making explicit the limitations of the assessment (AACN, 2007).

This includes detailing in the report whether interpreters were used, whether the patient’s language does not match the standardization of the tests, or whether the medico-legal situation requires caution when interpreting results. In informed consent it is advisable to explain what the assessment can and cannot provide, who will read the report and how data will be stored. When the case clearly exceeds the professional’s experience, the most responsible option is usually to refer or request supervision. Far from being a sign of weakness, this attitude reinforces the healthcare environment’s trust in the seriousness of neuropsychological work.

10. Forgetting professional self-care

Finally, a silent but common mistake in clinical neuropsychology practice: neglecting one’s own well-being. Neurorehabilitation exposes professionals to harsh stories, slow progress, relapses and limits that cannot always be overcome. Without spaces for support and reflection, the combination of high demands and unrealistic expectations makes compassion fatigue and burnout more likely (García-Molina & Prigatano, 2022; Ramos-Galarza & Gaibor, 2025).

Caring for the professional’s mental health involves accepting that not everything is modifiable, celebrating small functional changes, sharing difficult cases with colleagues, participating in supervision and setting reasonable limits on availability outside working hours. This perspective is not only a matter of individual well-being: teams that take care of themselves tend to sustain intensive and prolonged rehabilitation programs better, which directly improves the quality of care provided.

Conclusion

Making mistakes when starting practice in neuropsychology is inevitable; repeating them without analyzing them is not. Calmly reviewing how we assess, report, intervene, coordinate and take care of ourselves allows a shift from defensive practice, focused on “not making mistakes”, to a clinical neuropsychology that is more useful for patients and more sustainable for the professional. At bottom, it is something easy to state and complex to sustain: that every decision from the test we choose to the recommendation we write makes sense for the specific person in front of us.

Bibliography

- American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology, Board of Directors. (2007). American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (AACN) practice guidelines for neuropsychological assessment and consultation. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 21(2), 209–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825580601025932

- Cappa, S. F., Benke, T., Clarke, S., Rossi, B., Stemmer, B., & van Heugten, C. M. (2005). EFNS guidelines on cognitive rehabilitation: Report of an EFNS Task Force. European Journal of Neurology, 12(9), 665–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01330.x

- Cicerone, K. D., Dahlberg, C., Kalmar, K., Langenbahn, D. M., Malec, J. F., Bergquist, T. F., Felicetti, T., Giacino, J. T., Harley, J. P., Harrington, D. E., Herzog, J., Kneipp, S., Laatsch, L., & Morse, P. A. (2000). Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Recommendations for clinical practice. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 81(12), 1596–1615. https://doi.org/10.1053/apmr.2000.19240

- Cicerone, K. D., Dahlberg, C., Malec, J. F., Langenbahn, D. M., Felicetti, T., Kneipp, S., Ellmo, W., Kalmar, K., Giacino, J. T., Harley, J. P., Laatsch, L., Morse, P. A., & Catanese, J. (2005). Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Updated review of the literature from 1998 through 2002. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 86(8), 1681–1692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.024

- Cicerone, K. D., Langenbahn, D. M., Braden, C., Malec, J. F., Kalmar, K., Fraas, M., Felicetti, T., Azulay, J., Cantor, J., & Ashman, T. (2011). Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Updated review of the literature from 2003 through 2008. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(4), 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.11.015

- Cicerone, K. D., Goldin, Y., Ganci, K., Rosenbaum, A., Wethe, J. V., Langenbahn, D. M., Malec, J. F., Bergquist, T. F., Kingsley, K., Nagele, D., Trexler, L., Fraas, M., Bogdanova, Y., & Harley, J. P. (2019). Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Systematic review of the literature from 2009 through 2014. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(8), 1515–1533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2019.02.011

- García-Molina, A., & Prigatano, G. P. (2022). George P. Prigatano’s contributions to neuropsychological rehabilitation and clinical neuropsychology: A 50-year perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 963287. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.963287

- Ramos-Galarza, C., & Gaibor, J. (2025). Clinical perspectives on neuropsychological rehabilitation: Challenges, expectations, and family involvement. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 19, 1581304. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2025.1581304

- Ramos-Galarza, C., & Obregón, J. (2025). Neuropsychological rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(4), 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041287

Frequently asked questions about clinical practice in neuropsychology

1. What mistakes are common when starting in clinical neuropsychology?

When starting, errors often appear in assessment, interpretation, diagnosis, reports, intervention, coordination and self-care. These failures can wear down the professional and reduce the impact of the intervention if they are not reviewed and corrected with clinical criteria and available evidence.

2. Why avoid fixed batteries in neuropsychological assessment?

Always applying the same battery can prolong the assessment, tire the user and provide data of little relevance. A flexible assessment guided by hypotheses and a specific clinical question is recommended, selecting informative tests for the case rather than rigid protocols.

3. How to link neuropsychological results with daily life?

Scores should be interpreted together with the clinical and functional history, describing previous and current changes and functional consequences in activities of daily living. The goal is to translate the cognitive profile into implications for safety, autonomy and participation, not just percentiles.

4. What are the risks of overinterpreting tests and diagnosing quickly?

Diagnosing hastily can amplify false positives and erroneous conclusions, especially with many tests. It is recommended to interpret convergent patterns, consider validity and factors such as fatigue, education, language or motivation, and prioritize longitudinal follow-up in evolving processes.

5. How to write brief, actionable neuropsychological reports?

A useful report includes an initial summary with the reason for referral, essential findings and conclusions, groups results by domains and connects them with functional consequences. Recommendations should be presented in a prioritized manner, indicating priorities, aspects to monitor and referrals when appropriate.

6. How to prevent burnout and respect ethical limits in neuropsychology?

It is recommended to work within one’s competence, make limitations explicit (language, interpreters, medico-legal context) and seek supervision or refer if the case exceeds one’s capacity. To prevent compassion fatigue and burnout, reasonable limits, support from other neuropsychology professionals and supervision spaces are helpful.

If you liked this article about the most common mistakes when starting clinical practice in neuropsychology and how to avoid them, you will likely be interested in these NeuronUP articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Errores más comunes al iniciar la práctica clínica en neuropsicología y cómo evitarlos

How ASPAYM CyL Uses NeuronUP to Address All the Center’s Specialties

How ASPAYM CyL Uses NeuronUP to Address All the Center’s Specialties

Leave a Reply