As previously noted in earlier posts, the theoretical model most used when addressing attention is the clinical model of Sohlberg and Mateer, in which five hierarchically ordered levels are established, with the alternating attention being the fourth level. This means that to properly carry out an activity requiring alternating attention, good functioning of focused, sustained, and selective attention is required1.

But what is alternating attention? Can it be rehabilitated? We explain what it is and the ways to rehabilitate alternating attention.

Alternating attention

Thus, by way of definition, alternating attention is the cognitive capacity to shift the focus of attention between two or more activities that impose different cognitive demands. This requires mental flexibility that allows switching and performing the different tasks efficiently, without the cognitive load required by one task limiting the performance of the others, or the task switching itself disrupting concentration1.

The involvement of the lower levels of attention is clear. On one hand, focused attention, the most basic, is needed to be able to respond to different stimuli. On the other hand, sustained attention is engaged to carry out each of the tasks properly. And finally, selective attention is essential so that the information used in one or several tasks does not interfere with the activity being carried out at a given moment.

For example, one of the activities to work on alternating attention included in the Attention Process Training (APT) consists of a cancellation task. In this, the participant is asked to cross out one type of symbol, and change the target stimulus to another symbol at the moment the evaluator says “change”2. As can be seen, it is a cancellation task in which one has to sustain attention on the target stimulus and ignore the other stimuli until the change occurs, at which point mental flexibility comes into play.

When is alternating attention engaged?

There are many situations in which we put this type of cognitive process into operation in our daily lives, as we are constantly performing several tasks at the same time.

To illustrate, we can take preparing a meal as an example. Suppose we have a soup on the stove that we have to stir at certain intervals, and we use the periods when we are not stirring to chop other foods that we will later add to the soup. Here we have two tasks, stirring and chopping, and each requires performing a pattern of movements and a different cognitive load, since chopping an onion requires more attention and care to avoid cutting ourselves than stirring a soup. They may seem relatively simple tasks, however, for people who for some reason have problems with alternating attention, this would be very complicated, since they need more time to shift the focus of attention, resume, and begin new task demands.

Assessment of alternating attention

The tests commonly used to evaluate alternating attention generally involve other cognitive processes. Among the most used are the TMT-B, the letters and numbers subtest of the WAIS, and the symbols and digits, which are briefly described below.

The Trail Making Test (TMT) is one of the most used tests in neuropsychology to assess attention and executive functions. It is composed of two parts. On the one hand, the TMT-A involves a series of 25 circles presented randomly, each with a number, and the participant’s task is to connect the circles in ascending order as quickly as possible. On the other hand, in TMT-B, the circles—which in this case contain 13 numbers and 12 letters—must be connected in ascending and alternating order. This second part of the test is generally used to assess executive functions and alternating attention, since it requires mental flexibility to perform the alternation3.

The items of the Letters and Numbers subtest of the WAIS-IV consist of a series of letters and numbers mixed together that are presented to the participant orally. The task consists of repeating the numbers from smallest to largest and the letters in alphabetical order. It is used to assess alternating attention, concentration and working memory4.

Finally, the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) is used to evaluate attention and the processing speed. The participant’s task is to place beneath a series of symbols the number that corresponds to each according to a predetermined key. The test contains a total of 110 items and as many associations as possible must be completed in 90 seconds5.

Rehabilitation of alternating attention

As with any rehabilitation program, it is necessary to start by training the patient with simple tasks. This means short exercises, with few stimuli and long change intervals. As rehabilitation progresses these variables should be modulated so that the time the person must spend doing the task increases. Also, the stimuli should increase in number and complexity, the frequency of changes should increase, and the duration of each stimulus, in the case of a virtual program, should decrease.

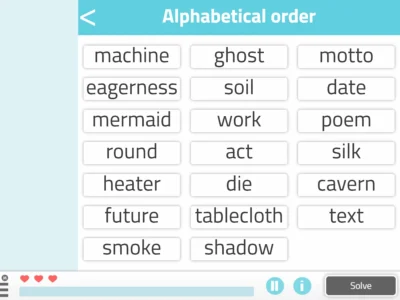

For this purpose there are several rehabilitation programs mentioned above, such as the APT or the platform NeuronUP, in which work is done through pencil-and-paper activities or computer programs. But this modality of tasks is not the only one used, since it has been shown that using music as a rehabilitative tool can achieve considerable improvements.

Music as a rehabilitative tool

Over the past decades, study of the benefits of music in all its variants has increased. Either passively, that is, listening to music to improve mood and even cognitive functions6, or actively through practicing an instrument7,8 or through dance9,10. Since the results have been positive, rehabilitation programs employing music as a tool have been implemented. An example is the Musical Attention Training Program (MATP), an adaptation of APT, in which four of the five attention levels of APT are worked on, but with musical stimuli11.

Rehabilitation program for alternating attention with music

In the case of rehabilitating alternating attention, the exercise modality is as follows: a melody is presented and each time the participant hears a particular, previously established sound pattern, they must press a computer key. At a given moment a drum rhythm track is presented, and the participant must press the key to produce a percussion sound together with the drum track on the beat of each measure. When the rhythm track disappears attention must return to the melody, thus alternating both task conditions during the duration of the exercise, which progressively increases as rehabilitation advances.

One advantageous aspect of the rehabilitation program is that it offers several types of music—rock, pop, reggae, etc.—so the training can be personalized according to each person’s tastes, thereby increasing motivation11.

Once again, it is worth noting the importance of adapting rehabilitation programs and tailoring them to patients’ needs, using tasks that have ecological validity and are motivating for the patient. In this way, an increase in cooperation and participation in rehabilitation will be achieved, also facilitating the extrapolation of results obtained in the clinic to the person’s daily life.

References

- Sohlberg MM, Mateer CA. Effectiveness of an attention-training program. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1987;9(2):117–30.

- Sohlberg MM, Mateer CA. Improving Attention and Managing Attentional Problems. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;931(1):359–75.

- Reitan, R. M. (1958). The validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organicbrain damage. Perceptual andMotor Skills, 8, 271-276.

- Amador, J. A. (2013). Escala de inteligencia de Wechsler para adultos-IV (WAIS-IV).

- Arribas, D. (2002). Symbol digitmodalities test (Test de Símbolos y Dígitos). Madrid: TEA Ediciones S.A.

- Särkämö, T., Tervaniemi, M., Laitinen, S., Forsblom, A., Soinila, S., Mikkonen, M., … &Peretz, I. (2008). Music listeningenhancescognitiverecovery and mood after middle cerebral arterystroke. Brain, 131(3), 866-876.

- Forgeard, M., Winner, E., Norton, A., &Schlaug, G. (2008). Practicing a musical instrument in childhood is associated with enhanced verbal ability and nonverbal reasoning. PloSone, 3(10), e3566.

- Schneider, S., Schönle, P. W., Altenmüller, E., &Münte, T. F. (2007). Using musical instruments to improve motor skill recovery following a stroke. Journal of Neurology, 254(10), 1339-1346.

- Hackney, M. E., & Earhart, G. M. (2009). Effects of dance on movement control in Parkinson’s disease: a comparison of Argentine tango and American ballroom. Journal of rehabilitation medicine, 41(6), 475-481.

- Earhart, G. M. (2009). Dance as therapy for individuals with Parkinson disease. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine, 45(2), 231.

- Knox R, Yokota-Adachi H, Kershner J, Jutai J. Musical attention training program and alternating attention in brain injury: An initial report. Music Therapy Perspectives. 2003;21(2):99-104.

If you liked this article about alternating attention, you might also be interested in:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

La atención alternante y sus formas de rehabilitación

Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis with NeuronUP

Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis with NeuronUP

Leave a Reply