Psychologist, professor, researcher and holder of a master's degree in human development and education, Carolina Robledo Castro offers us in this article a brief overview of the history of ADHD and how it affects executive functioning in those who have it.

What is ADHD

Currently, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the clinically endorsed term to refer to a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by behaviors of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity (APA, 2013). However, this concept remains a developing psychological construct, which has gone through different conceptions and approaches over the decades and will likely continue to evolve.

Clinical evolution of ADHD

Alexander Crichton

The first clinical approaches to what we today know as ADHD can be seen as far back as the 17th century, when the physician Alexander Crichton, based on various clinical observations, published a work titled “On Attention and its Diseases” in which he described a condition characterized by the inability to sustain attention to any object accompanied by a constant motor restlessness which he called mental restlessness (Mental Restlessness) and that resembles the current description of ADHD (Lange, 2010).

Heinrich Hoffmann

An allusion to the manifestations of ADHD has also been identified in the writings of physician Heinrich Hoffmann in 1844. Hoffmann wrote a series of illustrated stories that describe the impulsive and inattentive behavior of a boy he called “Fidgety Phil” (Struwwelpeter), stories that were based on the observation of his own son (Filomeno, 2007). Although Hoffmann’s approach was not clinical, the story of Fidgety Phil is often used as an allegory for ADHD (Lange, 2010).

George Frederic Still

In the field of pediatrics, one of the first to carry out a clinical approach to this condition was George Frederic Still, who in 1902 described a pattern of behavior in children who displayed lack of attention and seemed to lack control over their behavior.

Initially, Still attributed this behavior to a defect of moral control, but later associated it with a possible neurological or hereditary disease (Robledo, 2017; Filomeno, 2007). Later, this pattern of inattention and impulsivity was associated with encephalitis lethargica during the epidemic that spread between 1917 and 1928, since those affected presented similar cognitive and behavioral alterations:

- significant changes in personality,

- emotional instability,

- cognitive deficits,

- learning difficulties,

- poor motor control.

This condition was called “minimal brain damage“, and it remained until the seventies, when it was renamed “minimal brain dysfunction” (Lange, 2010).

ADHD from the 1930s to the 1960s

Between the 1930s and 1950s, the medical community placed special emphasis on symptoms of impulsivity and hyperactivity above cognitive manifestations, and the term changed to hyperkinetic syndrome, a notable motor activity that makes children unable to stay still for even a second.

The influence of behavioral perspectives in the 1960s notably initiated the work of authors such as Stella Chess and it began to be referred to as hyperactive child syndrome (Robledo, 2017).

Finally, in 1968, this condition was included for the first time in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM II, (APA, 1968) under the name of hyperkinetic reaction.

ADHD from the 1970s to the 1990s

Sustained attention difficulty and lack of impulse control regained recognition in the 1970s with the work of Virginia Douglas (Douglas, 1972). By the 1980s, the Diagnostic Manual of Mental Disorders in its third edition established that hyperactivity was not a differential diagnostic criterion for the disorder, so it coined the term Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) and indicated that it could present in two types with hyperactivity and without hyperactivity (APA, 1980).

At the beginning of the 1990s, the DSM-IV coined the term attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and expanded the classification of this disorder by distinguishing the subtypes: inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive or combined (APA, 1990).

At that time this disorder was categorized in the group of disorders with onset in childhood and adolescence, specifically in the classification of attention disorders and disruptive behavior.

ADHD from the 1990s to the present

From the 1990s to the present, advances in neuroscience, genetics, the use of diagnostic imaging and computational modeling have been forerunners of new knowledge that has expanded the conceptualization and approach to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

With the most recent diagnostic manual, DSM-5, some representative changes were incorporated in the way ADHD is conceptualized and understood. Although most of the diagnostic criteria from the previous version are retained, ADHD has now been incorporated into the division of neurodevelopmental disorders along with several others such as autism spectrum disorder. Additionally, for the first time within the diagnostic criteria, it is recognized that this condition is not exclusively a childhood disorder, but can persist into adolescence and adulthood; it is also differentiated in levels of mild, moderate and severe (APA, 2013).

As a result of more than 40 years of work with children, adolescents and adults who presented this pattern of behavior, Russel Barkley (2002) stated: “I now view ADHD as a developmental disorder of the ability to regulate one's own behavior and to foresee the future” (p.35).

Barkley, supported by the scientific advances of the time, concluded that ADHD stems from the hypoactivity of a brain area whose function is to provide greater resources for behavioral inhibition, self-regulation, self-organization and foresight as the individual grows and this neurological area matures. Moreover, this hypoactivity leads to a deficit in people's ability to regulate their daily functioning, adapt to environmental demands and prepare for the future.

In the 2000s, scientific findings confirmed alterations in biochemical mechanisms in the prefrontal cortex in individuals with ADHD, especially in the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine (Nigg 2006, Duda 2011).

Neuroimaging research suggests a possible delay of up to three years in the maturation of the prefrontal cortex in those with ADHD (Shaw 2007), as well as an association between ADHD and an alteration of the volume and level of activation in prefrontal areas related to executive functions (Seidman et al., 2005).

Based on these discoveries and other clinical findings, authors such as Brown (2002) and Barkley (2011) have suggested that ADHD does not primarily originate in an attention deficit, but is the result of an alteration in the synaptic circuits of certain brain areas, including the prefrontal neocortex, which play a crucial role in regulation and cognitive control. Consequently, it has been concluded that deficits in organization and self-management in individuals with ADHD are linked to the alteration in executive functioning (Barkley, 1997; 2011).

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

What are executive functions

Executive functions (EF) are cognitive processes that allow the individual to internalize behaviors to anticipate future changes and, in this way, maximize the individual's long-term benefits (Barceló, 2005; Flores & Ostrosky-Shejet, 2012).

They are precursors of successful self-regulation capacity (Kalbfleisch, 2017), thus being crucial for school learning, following instructions, complying with rules and general functioning in daily life.

They are involved in carrying out goal-directed tasks, those that involve reviewing options, organizing, planning, monitoring execution, anticipating future consequences, evaluating performance and adapting to new situations (Portellano & García, 2014). In other words, these cognitive processes make it possible to plan, organize, guide, review, regulate and evaluate behavior in the pursuit of goals.

Executive functions affected by ADHD

According to Brown (2008) the EFs affected in people with ADHD are the following:

- Activation, required to organize tasks and materials, estimate time, set task priorities and initiate activity;

- focusing, necessary to focus and sustain attention, as well as shift the focus of interest;

- regulation of effort, which includes management of alertness state, tolerance to fatigue and processing speed;

- emotional management, which allows the individual to handle frustration and control emotions;

- working memory responsible for retaining incoming information and retrieving stored information until a task is completed;

- and action control, which allows monitoring behavior, learning from mistakes and inhibiting automatic and impulsive responses.

Challenging activities due to ADHD

Based on the findings of Brown (2008), Beatriz Duda (2011) provides a description of activities associated with executive functioning that tend to be challenging for children, adolescents and adults with ADHD, which have been compiled in the following table:

| Executive function (Brown, 2008) | Subfunction | Activities that people with ADHD find difficult (Duda, 2011) |

|---|---|---|

| Focus: Ability to focus attention on what is important, maintain and shift attention in certain tasks. | Focus | Direct their attention to what is important. Ej. pay attention to the teacher instead of talking to classmates. |

| Maintain focus | Sustain attention for the time a class lasts. Or alternate attention between two tasks. | |

| Flexibility | Ej. Stop browsing the internet and start writing. | |

| Action: Ability to evaluate one’s own behavior, recognize difficulties, self-regulate, inhibit impulses and automatic behaviors. | Inhibition | Avoid automatic behaviors, wait one's turn, delay rewards. Ej. Run out at recess. |

| Self-monitoring | Manage time efficiently. Recognize mistakes and successes as learning for future situations. | |

| Emotion: Ability to control and manage affective states, to react with the appropriate emotional level in response to circumstances. | Frustration management | Stay calm when things are not going as he wants. |

| Emotion regulation | React appropriately to situations. Ej. Shouting or hitting when something bothers them. | |

| Working memory: Ability to hold in mind information necessary to follow the actions. | Retain | Keep necessary information while carrying out a task. Ej. In a conversation, not remembering what one was talking about after being interrupted. |

| Retrieve | Access important information. Ej. Study for a test and not recall it at the time of the exam. | |

| Sustained effort: Regulation of alertness state, maintenance of effort and speed of information processing. | Processing speed | Complete tasks within the allotted time. Ej. They need more time than their classmates to finish a task. |

| Maintaining effort | Tolerance to fatigue. Ej. Their attention wears out faster than other boys and girls. | |

| Regulate alertness state | Maintain alertness in activities that are not motivating. | |

| Activation: Ability to get oneself ready to work, establish a priority order and plan actions based on projected goals over time. | Get started | Get up in the morning and start the day's activities. Stop playing and start doing homework. |

| Prioritize | Decide what to do first and establish the order of actions according to priorities. Ej. They start many things at once. | |

| Organize | Keep things in order. Ej. Difficulty planning how to resolve a situation. |

Intervention and rehabilitation of executive functions in children with and without ADHD

With regard to intervention and rehabilitation of executive functions in children with and without ADHD, Diamond (2011; 2012) differentiates four types of interventions that have shown promising results:

- cognitive training,

- mindfulness practices aimed at regulating attention,

- curricular approaches with emphasis on cognitive scaffolding,

- programs focused on social skills and emotional regulation.

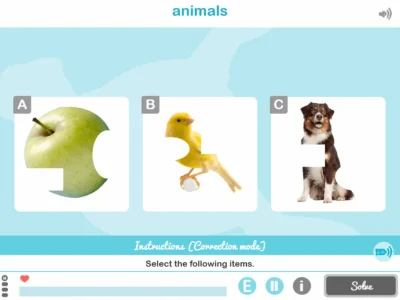

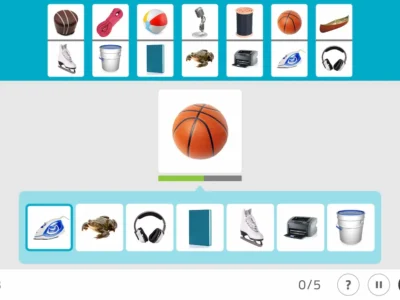

Computerized cognitive training

Computerized cognitive training has been one of the most implemented interventions to improve executive functions and reduce symptoms of impulsivity and inattention in the context of ADHD (Pauli-Pott et al., 2021; Robledo et al., 2023).

This type of intervention seeks to optimize cognitive functioning through the practice of intentional instructions and distinguishes two paradigms:

- one based on processes, where the individual repeats the execution of a task

- another based on strategies, where various strategies are explored to approach a specific task (Jolles and Crone, 2012; Portellano, 2018).

Some systematic reviews and meta-analyses have compiled evidence from clinical studies and controlled trials in which computerized cognitive training has been implemented for stimulation and rehabilitation of executive functions in populations with ADHD (Sonuga-Barke et al., 2014; Alabdulakareem and Jamjoom, 2020; Robledo et al., 2023).

These works have found that computerized cognitive trainings had effects on:

- attention and memory;

- the reduction of ADHD symptoms in children and adolescents (Sonuga-Barke et al., 2014);

- positive effects on executive functions such as attention, inhibitory control and working memory (Robledo et al., 2023);

- improvements in academic performance and self-control of children with ADHD;

- a greater satisfaction and adherence to treatment (Alabdulakareem and Jamjoom, 2020).

Although to date evidence has been collected on the uses and benefits of computerized cognitive trainings on children's executive functions and ADHD symptoms, this remains a field of study still in development that undoubtedly has wide relevance and interest for the academic community, as well as for all professionals in charge of the care and intervention of the population with ADHD.

Bibliography

- APA – American Psychiatric Association (1968) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (2nd Edition) (DSM-II). American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC.

- APA – American Psychiatric Association (1980) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd Edition) (DSM-III). American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC

- APA – American Psychiatric Association (1990) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd Edition) (DSM-IV). American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC

- APA – American Psychiatric Association. (2014). DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria Guide Washington: Author.

- Barkley, R. (2002). Hyperactive Children: How to Understand and Attend to Their Special Needs. 3rd ed. Barcelona: Paidós.

- Barkley, R. (2011). Executive functioning and self- regulation: Integration, extended phenotype, and clinical implications. The Guilford Press.

- Barkley, R.A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions. Psychological Bulletin, 121 (1), 65-94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65

- Barkley, R.A. & Edwards, G. (1998). Diagnostic interview, behavior rating scales and the medical examination. In R.A. Barkley, Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (2 ed.) (pp.510-551). The Guilford Press.

- Bauermeister, J. (2014). Hyperactive, Impulsive, Distracted: Do You Know Me?. 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Brown, T.E. (2005). Attention Deficit Disorder. The Unfocused Mind in Children and Adults. New Heaven: Yale University Press.

- Douglas, V.I. (1972). Stop, look and listen: The problem of sustained attention and impulse control in hyperactive and normal children. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 4, 259-282.

- Duda, B. (2011). Coaching for ADHD: Theoretical and Practical Aspects. Lima: Peruvian Association for Attention Deficit

- Filomeno, A. (2009). The child with attention deficit or hyperactivity: how to go from failure to success. 2nd ed. Lima: Universidad San Cayetano de Heredia.

- Flores, J. & Ostrosky-Shejet, F. (2012). Neuropsychological development of the frontal lobes and executive functions. Mexico DF: Manual Moderno.

- Jolles, D., & Crone, E. (2012). Training the developing brain: A neurocognitive perspective. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00076

- Kalbfleisch, L. (2017). Neurodevelopment of the executive functions. In Executive functions in health and disease (pp. 143-168). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803676-1.00007-6

- Lange, K. W., Reichl, S., Lange, K. M., Tucha, L., & Tucha, O. (2010). The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders, 2(4), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-010-0045-8

- Nigg, J. (2006). What Causes ADHD?: Understanding What Goes Wrong and Why. New York NY: The Guilford Press

- Pauli-Pott, U., Mann, C., & Becker, K. (2021). Do cognitive interventions for preschoolers improve executive functions and reduce ADHD and externalizing symptoms? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(10), 1503-1521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01627-z

- Portellano, J. A., & García Alba, J. (2014). Neuropsychology of attention, executive functions and memory. Síntesis.

- Portellano, J.A. & García, J. (2014). Neuropsychology of attention, executive functions and memory. Editorial Síntesis.

- Robledo, C. (2018). Attention deficit and hyperactivity: Some questions and answers. Editorial imprint Universidad del Tolima

- Seidman, L. J., Valera, E. M., & Makris, N. (2005). Structural brain imaging of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychiatry, 57(11), 1263–1272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.019

- Shaw, P., Eckstrand, K., Sharp, W., Blumenthal, J., Lerch, J. P., Greenstein, D., Clasen, L., Evans, A., Giedd, J., & Rapoport, J. L. (2007). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(49), 19649–19654. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707741104

- Soprano, A. (2010). How to assess attention and executive functions in children and adolescents. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

If you liked this article about the history of ADHD and how it affects executive functioning, you might be interested in these NeuronUP articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Breve reseña histórica del ADHD y su afectación al funcionamiento ejecutivo

New Children’s Pre-Reading Activity: Rotated Letters

New Children’s Pre-Reading Activity: Rotated Letters

Leave a Reply