Neuropsychologist Ramón Fernández de Bobadilla explains in this article how to carry out a neuropsychological rehabilitation in Parkinson’s disease.

What is Parkinson’s disease?

Parkinson’s disease is the most common motor neurodegenerative disorder, with a prevalence in Europe estimated at 108-207 per 100,000 inhabitants. Although there is a minority of genetically originated cases, the cause is fundamentally unknown, with age being the main risk factor for its development.

The progression of the disease is very slow and much of its symptomatology results from the death of dopaminergic neurons and the consequent loss of terminals related to this neurotransmitter.

Symptoms of Parkinson’s disease

The four diagnostic pillars of Parkinson’s disease are:

- bradykinesia,

- rigidity,

- tremor

- postural instability.

Symptoms typically appear unilaterally and, although over time they become bilateral, asymmetry is generally maintained. Although the most publicly identifiable symptom of Parkinson’s disease is tremor, it is not a defining nor specific symptom. What truly defines Parkinson’s disease is parkinsonism. This necessarily implies the presence of bradykinesia (scarcity and slowness of voluntary movements, which will be evident on examination through impairment of repetitive movements).

Initial phase

After the onset of motor symptoms, patients present an initial phase with a good response to pharmacological therapy through dopaminergic replacement, which usually extends about 5 years.

Progression

From here, gradually, complications will develop and new symptoms will appear as neurodegeneration advances. The time elapsed from the onset of motor symptoms to disability is highly variable between patients, and generally ranges between 10 and 20 years.

Non-motor symptoms

Despite the importance of motor symptoms, increasing attention is being paid to the non-motor symptomatology of Parkinson’s disease. This is not only useful diagnostically (since they are found in all stages of the disease), but it is of vital importance for the monitoring and care of these patients due to their significant impact on quality of life.

Non-motor symptomatology is highly complex and encompasses both cognitive and neuropsychiatric aspects, as well as sleep disorders, autonomic dysfunction, gastrointestinal or sensory symptoms. Some of these symptoms may be generated or worsened by dopaminergic medication itself (dopamine dysregulation syndrome, hallucinations, psychosis, postural hypotension, daytime sleepiness, (etc.).

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease almost inevitably involves cognitive impairment during its course, and up to 80% of patients develop dementia after 20 years of progression. In early stages, approximately 30% of patients present mild cognitive impairment, this being an independent risk factor for the later development of dementia.

In addition to cognitive impairment, anxiety, depression, apathy, illusions and hallucinations are very common in Parkinson’s disease.

Cognitive disorders are today recognized as highly prevalent symptoms of vital importance to the quality of life of these patients.

Classically, they have been attributed to dopaminergic depletion secondary to neurodegeneration of the substantia nigra, which led to a deficit of this neurotransmitter at the striatal level and, consequently, to a failure of fronto-subcortical circuits.

However, in recent years this view has been broadened given the growing evidence of the involvement of cortical and extra-nigral structures.

Neuropsychological profile in Parkinson’s disease

Initial cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease may not be clinically apparent, and instead be detected with a structured neuropsychological assessment.

In this way, we can find cognitive deficits in apparently unaffected patients, these deficits being mostly of a dysexecutive nature.

In fact, the neuropsychological profile found in patients with Parkinson’s disease resembles that seen in patients with frontal lobe damage.

However, we may also find patients who from early stages present clinical complaints, such as difficulties in maintaining attention while reading, performing prolonged mental efforts or when they must carry out certain mental operations.

A characteristic feature is the difficulty in “finding the word” (“tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon“), which is related to deficits in semantic verbal fluency from very early stages.

Problems in the recall of recent episodic events are also frequent and are related to impairment on free recall verbal memory tests and visual memory tests.

Difficulties in performing simultaneous tasks, planning activities and organizing daily life (correspondence, finances, work projects) can be perceived very early by patients, and have been related to executive dysfunction.

Despite the early appearance of deficits in visual perception, this normally does not translate into complaints about motion perception or visual recognition by patients.

As cognitive impairment progresses, symptoms related to memory and executive functions become more evident both to the patient and to their surroundings.

Problems in the transition to dementia

In the transition to dementia, language problems arise, and patients with Parkinson’s disease encounter difficulties in language comprehension and production, and a tendency to lose the thread of conversation.

Language problems in middle and advanced stages are characterized by impaired sentence comprehension, poor verbal production and reduced semantic activation.

Therefore, systems other than the dopaminergic one and circuits different from the fronto-striatal must necessarily be affected in Parkinson’s disease. There is growing evidence that the involvement of the cholinergic system is of paramount importance in the cognitive disorder associated with Parkinson’s disease.

Neuropsychological rehabilitation in Parkinson’s disease

Some trials have studied the benefits that the use of cholinesterase inhibitors produces on cognition, behavior and quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease and dementia, but a pharmacological approach specifically aimed at treating mild cognitive impairment in these patients or preventing the progression of symptoms has not yet been approved.

However, although the evidence is still limited, an improvement in cognition in patients with Parkinson’s disease is also observed through non-pharmacological interventions.

The use of cognitive-behavioral therapy has demonstrated remarkable effectiveness as a treatment for depression and anxiety in these patients, resulting in a benefit in their ability to cope with the disease and improving their quality of life.

But what is increasingly being established as a key strategy to delay the decline toward stages close to dementia in Parkinson’s disease is work through the use of cognitive training, physical exercise or a combination of both.

Cognitive training has been shown to be safe and produces a measurable improvement in cognitive performance, particularly in working memory and executive functions, mainly in information processing speed.

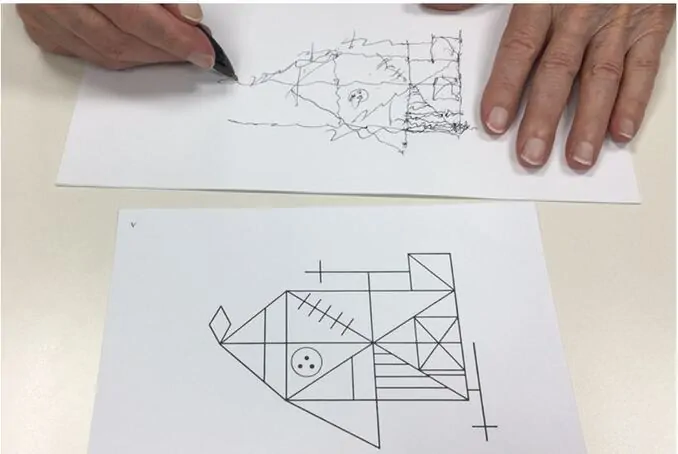

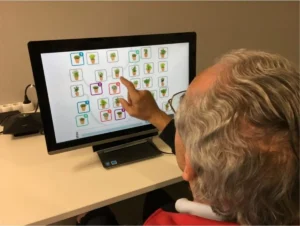

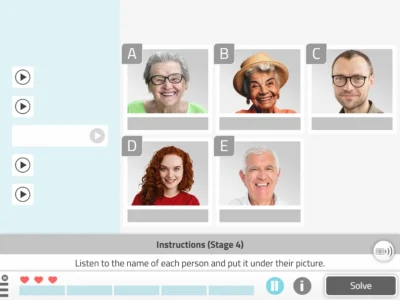

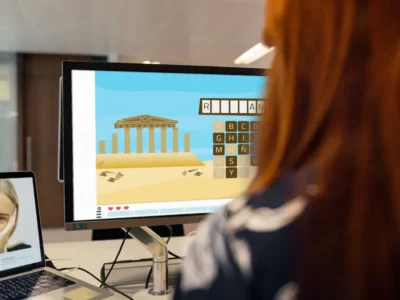

It is supported from the use of stimulation through paper-and-pencil tasks to strategies based on computerized programs.

Likewise, benefits have been observed with both generalized work and work focused on specific cognitive processes (mainly executive functions), as well as in exercises controlled through movement.

Conclusion

In conclusion, cognitive training in combination with behavioral interventions can help patients with Parkinson’s overcome the enormous challenge of living with this disease. Our goal as professionals or family members should always be to try to maximize their well-being and quality of life.

Although we are still in the early stages of research on the real benefits of these types of non-pharmacological strategies and methodological limitations in many cases are practically insurmountable due to the complexity of this disease, work aimed at optimizing them so that they are effective for patients, both in the early and advanced stages of the disease, is a huge challenge that should encourage us to continue working in this direction.

Bibliography

- Troster, A. I. [Ed]. (2015). Clinical neuropsychology and cognitive neurology of Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders. Clinical Neuropsychology and Cognitive Neurology of Parkinson’s Disease and Other Movement Disorders.New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press.

- Wilson, B. A., Winegardner, J., van Heugten, C. M., &Ownsworth, T. (2017). Neuropsychological Rehabilitation: The International Handbook. Taylor & Francis.

- Fernández de Bobadilla, R. (2017). Development and validation of new tools for the cognitive and functional assessment of mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Doctoral thesis. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona.

If you are a neuropsychologist or occupational therapist and what you want is to work on the main cognitive processes that affect people with Parkinson’s, don’t miss this article with cognitive stimulation exercises for people with this disease:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Rehabilitación neuropsicológica en la enfermedad de Parkinson

Chiari I Malformation. A Clinical Case

Chiari I Malformation. A Clinical Case

Hi, I wanted to know your price.