Psychologist Carlos Rebolleda explains the attributional style in schizophrenia, focusing on assessment and deficits.

Attributional style is one of the areas that make up the social cognition construct in the context of schizophrenia. It refers to how individuals infer the possible causes of personal events, both positive and negative (Green and Horan, 2010).

As Penn, Sanna and Roberts (2008) note, most research that has focused on studying attributional style in schizophrenia has attempted to investigate the genesis and maintenance of paranoid symptomatology that some of these people sometimes exhibit.

Assessment of attributional style in schizophrenia

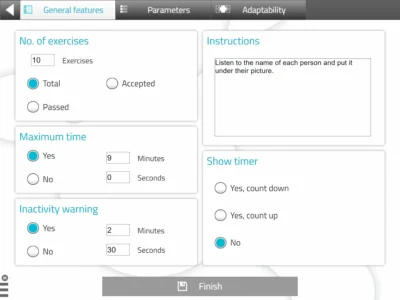

The tests commonly used to assess attributional style in schizophrenia are the following:

Attributional Style Questionnaire (Attributional Style Questionnaire, ASQ) (Peterson et al., 1982)

This test evaluates the three basic dimensions of attributional style known as locus (internal-external), stability (stable-unstable) and globality (global-specificity). The instrument is composed of 36 items corresponding to 12 situations (six positive and six negative). Once these scenarios are presented to the subjects, they are asked to rate them in relation to each of the three attributional dimensions.

Internal, Personal and Situational Attributions Questionnaire (Internal, Personal and Situational Attribution Questionnaire, IPSAQ) (Kinderman and Bentall, 1996)

The aim of this test is to observe the evaluated subject’s ability to discriminate between external personal attributions (causes attributed to other people), external situational attributions (causes attributed to situational factors) and internal attributions (causes that are due to oneself) in a total of 32 hypothetical situations, half of which are positive and the other half negative.

The Ambiguous Intentions Hostility Questionnaire (AIHQ) (Combs, Penn, Wicher and Waldheter, 2007)

This instrument measures attributional style by analyzing the subject’s possible tendencies to overattribute negative intentions to others and to respond to those intentions in a hostile way. During the test a series of vignettes describing different social situations are shown and, subsequently, the subject is asked about the characters’ intentions and about the response they themselves would give to these situations if they were to occur.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Deficits in schizophrenia

Individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia who exhibit paranoid symptomatology often show a tendency to blame others for negative events that happen to them. This attributional style is known as the “personalization bias” (Bentall, Corcoran, Howard, Blackwood and Kinderman, 2001; Garety and Freeman, 1999).

Factors

According to Bentall et al. (2001) there would be two factors that would negatively influence the ability of a person diagnosed with schizophrenia with paranoid symptomatology to correct their “personalization biases”.

- The first would be marked by a strong tendency to “close off” to options that discredit the other’s culpability, an aspect that would be expressed in behaviors characterized by intolerance or ambiguity.

- The second would relate to the presence of theory of mind deficits, understood as the individual’s ability to infer others’ mental states such as intentions, dispositions and beliefs (Green and Horan, 2010).

It has also been found that people who suffer from paranoid symptomatology show, apart from the mentioned “personalization bias”, other cognitive biases such as the tendency to “jump to conclusions” and to “prove the reality of their biases” (Freeman, 2007).

The attributional style characteristic of paranoid symptomatology is defined by a tendency to exaggerate, distort, or selectively focus on others’ hostile or threatening aspects (Fenigstein, 1997), with anger, disgust and contempt being the emotions usually associated with hostility (Barefoot, 1992; Brummett et al., 1998; Izard, 1994). It is worth recalling that, specifically for these emotions, people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia have been found to have more difficulty correctly interpreting them (Kohler et al., 2003).

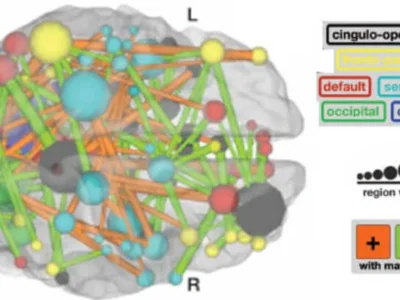

Neurological level

At the neurological level, various neuroimaging studies have shown that the hyperactivity found in the amygdala contributes to the deficits these subjects show when judging others’ intentions (Marwick and Hall, 2008).

Bibliography

- Barefoot, J. (1992). Development in the measurement of hostility. In H. Friedman (Ed), Hostility, coping and health (pp. 13-31). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bentall, R. P., Corcoran, R., Howard, R., Blackwood, N., and Kinderman, P. (2001). Persecutory delusions: a review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(8), 1143-1192

- Brummett, B. H., Maynard, K. E, Babyak, M. A., Haney, T. L., Siegler, I. C., Helms, M. J., and Barefoot, J. C. (1998). Measures of hostility as predictor of facial affect during social interaction: evidence for construct validity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 20(3), 168-173.

- Combs, D. R., Penn, D. L., Wicher, M., and Waldheter, E. (2007). The Ambiguous Intentions Hostility Questionnaire (AIHQ): a new measure for evaluating hostile social-cognitive biases in paranoia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 12(2), 128-143.

- Fenigstein, A. (1997). Paranoid thought and schematic processing. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 16(1), 77-94

- Freeman, D. (2007). Suspicious minds: the psychology of persecutory delusions. Clinical Psychological Review, 27(4), 425-467.

- Garety, P. A., and Freeman, D. (1999). Cognitive approaches to delusions: a critical review of theories and evidence. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(2), 113-154.

- Green, M. F., and Horan, W. P. (2010). Social cognition in schizophrenia. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(4), 243-248.

- Izard, C. (1994). Innate and universal facial expressions: evidence for development and cross-cultural research. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 288-299

- Kinderman, P., and Bentall, R. P. (1996). A new measure of causal locus: the internal, personal and situational attributions questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 20(2), 261-264.

- Kohler, C. G., Turner, T. H., Bilker, W. B., Brensinger, C., Siegel, S. J., Kanes, S. J.,… and Gur, R. C. (2003). Facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: intensity effects and error pattern. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(10), 1768-1774.

- Marwick, K., and Hall, J. (2008). Social cognition in schizophrenia: a review of face processing. British Medical Bulletin, 88(1), 43-58.

- Penn, D. L., Sanna, L. J., and Roberts, D. L. (2008). Social Cognition in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(3), 408-411

- Peterson, C., Semmel, A., Von Baeyer, C., Abramsom, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., and Seligman, M. E. P. (1982). The attributional style questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6(3), 287-299

If you liked this post about attributional style in schizophrenia, you may also be interested in the following articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Estilo atribucional en esquizofrenia

Embodied memory: The influence of body posture on autobiographical memory

Embodied memory: The influence of body posture on autobiographical memory

Leave a Reply