Neuropsychology specialist María Teresa explains in this article what traumatic brain injury is and its neuropsychological rehabilitation in executive functions.

What are Traumatic Brain Injuries (TBI)?

It is defined as an alteration in brain functioning, caused by an external force (Menon, Schwab, Wright and Maas, 2010).

Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) are a critical public health problem, both because of their high mortality rates and the disabilities presented by patients who survive them, displaying difficulties at the level of:

Cognitive, emotional, family, social and occupational.

These affect their quality of life (Arango-Lasprilla, Quijano and Cuervo, 2010; Corrigan, Selassie and Orman, 2010; García-Rudolph and Gibert, 2015; Park et al., 2015; Santana et al., 2015).

In neuropsychology, the design of rehabilitation programs is carried out from the cognitive approach, since it is considered that improving the mental capacity of patients with traumatic brain injury has a direct effect on their functionality.

Types of traumatic brain injury (TBI):

Open TBIs

Open traumatic brain injuries occur when a fracture or perforation of the cranial vault happens, producing a wound in the brain tissue and exposing or leaving the brain mass in contact with air.

Closed TBIs

Closed traumatic brain injuries only affect brain tissue (León-Carrión, 1995).

Both types of injuries usually present a focal and a diffuse affectation, due to the impact received. The first corresponds to the lesion generated in the area of the brain that received the impact. The second is one that does not occupy a well-defined volume within the intracranial compartment, but which, like the focal lesion, produces neurological sequelae (González, Pueyo and Serra, 2004).

Commonly, focal damages are characterized by alterations in the functioning of the frontal and temporal lobes, since these are the areas most susceptible in closed TBIs; in open injuries, it will depend on the place where the skull bone can be affected. For its part, diffuse damages tend to cause loss in complex cognitive functions such as processing speed, concentration and cognitive efficiency in general (Kolb and Whishaw, 2014).

Severity of traumatic brain injury

The severity of traumatic brain injury is usually classified into three levels, according to the time the person remains unconscious or with traumatic amnesia:

mild, moderate, severe.

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)

The standard measure to define the severity level of TBI is known as the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). It assesses three independent parameters with which it defines the patient’s level of conscious response:

- Verbal response

- Motor response

- Eye opening

Scores

The higher the score, the better level of consciousness the patient presents (Hoffmann et al., 2012; Muñana-Rodríguez and Ramírez-Elías, 2013; Santa Cruz and Herrera, 2006; Poca, 2006):

- Scores between 14-15: correspond to a mild traumatic brain injury,

- scores between 9-13: moderate,

- scores less than or equal to 8: severe

Assessment of brain damage

The severity of brain damage should be evaluated as soon as possible, preferably once the injury has occurred to provide a baseline for future assessments and to act timely, both to medically stabilize the patient and to begin rehabilitation processes if required (Hoffmann et al., 2012; Muñana-Rodríguez and Ramírez-Elías, 2013; Santa Cruz and Herrera, 2006; Poca, 2006).

Intervention after suffering a TBI

Post-injury intervention typically includes physical and cognitive rehabilitation. The latter should be directed at high-level cognitive functions, such as executive functions, since they tend to be among the most affected, both in focal and diffuse damages caused by TBI (García-Molina, Enseñat-Cantallops, Sánchez-Carrión, Tormos and Roig-Rovira, 2014).

Executive functions in a person with traumatic brain injury

The concept of executive functioning refers to a set of high-level cognitive operations such as planning, decision-making, flexibility, among others, which control and regulate behavior, directing it toward a goal, forming objectives and planning how they can be carried out.

These same functions are also recognized as essential mental capacities for carrying out creative and socially acceptable behavior.

Furthermore, executive functions become more complex throughout development; some of them have an early appearance, which enables the emergence and complexification of other executive functions (Bombín-González et al., 2014; Tirapu-Ustárrez, García-Molina, Luna-Lario, Verdejo-García and Rios-Lago, 2012).

For Tirapu-Ustárrez et al. (2017), the systematic review of factor analyses of executive functions resulted in an integrative proposal of executive control processes, such as:

- Processing speed: amount of information that can be processed per unit of time or the speed to perform cognitive operations;

- working memory: capacity to register, encode, maintain and manipulate information online;

- verbal fluency: ability to access and retrieve information from semantic memory and activate word search;

- inhibition: control of interference and distractors or selective attention,

- dual-task execution: ability to attend simultaneously to multiple stimuli,

- cognitive flexibility: switching,

- planning: monitoring and control of behavior,

- decision making: role of emotions in reasoning.

Executive function plays a primary role in human life, since it involves a set of cognitive processes with different independent components, but with intimate relationships among them to control and modulate behavior.

Once these functions are affected by neurological damage, such as in a traumatic brain injury, executive deficits generate a multiplicity of cognitive, behavioral and emotional manifestations, which interfere with the person’s adequate functioning in daily life, creating difficulties in recovering a normal and productive life.

Neuropsychological rehabilitation in patients with TBI

Rehabilitation can be defined as a systematic application of therapeutic activities, aimed at improving the patient’s functionality, based on the understanding of their deficits (Cicerone et al. as cited in van Heugten, Gregório and Wade, 2012).

The intervention must have ecological validity, so that it has a real impact on the patient’s daily life, with the objective that they can extrapolate and generalize into their everyday life what was learned in the clinic (Carvajal-Castrillón and Restrepo, 2013).

Personalized assessment and rehabilitation programs

The proposals of cognitive rehabilitation, from contemporary neuropsychology, suggest the development of individualized assessment and rehabilitation programs for each pathology, with clear and common expectations and goals for the patient and their family (Calderón, Cadavid-Ruiz and Santos, 2016; Carvajal-Castrillón and Restrepo, 2013; Ríos, Muñoz and Paúl-Lapedriza, 2007; Tate, Aird and Taylor, 2013).

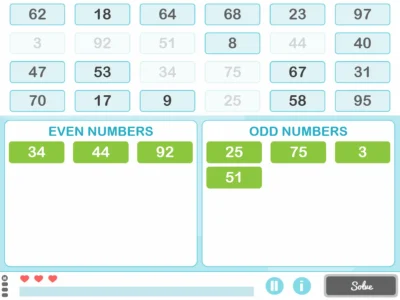

Their rehabilitation programs consist of tasks organized hierarchically by level of difficulty that require the repetitive use of the impaired functions. These programs clarify that the degree of functional recovery of the patient will depend on the number of repetitions and the type of task performed during treatment (García-Rudolph and Gibert, 2015).

In neuropsychology the design of rehabilitation programs is carried out from the cognitive approach, since it is considered that improving the mental capacity of patients has a direct effect on their functionality.

In addition, these programs emphasize the importance of adapting programs to the individual needs of the patient using restorative or compensatory techniques. The former refers to strengthening, reinforcing or restoring the deteriorated cognitive processes; the latter presents ways to compensate for the altered function through the use of external resources for the patient, for example, reminders or alarms, among others (Barman et al., 2016; Evald, 2015; Tsaousides, D’Antonio, Varbanova and Spielman, 2014).

That said, cognitive rehabilitation must take into account that traumatic brain injury is a medical condition that involves various fields of health; it requires:

- Neurological management to modulate and supervise the damage caused to the brain tissue,

- a neuropsychological intervention to recover the highest possible degree of functionality in the patient,

- social management to support the patient’s functionality in the everyday contexts in which they may operate.

Research findings

Findings from research on rehabilitation in patients with traumatic brain injury indicate that the best results are achieved when intervention programs aim for a comprehensive and interdisciplinary management of the medical and psychosocial condition experienced by the patient, which includes intervention in their cognitive, emotional, family and social spheres.

These initiatives should not only aim at the rehabilitation of the patient with TBI, but also be directed toward the promotion of their health, which implies the implementation of measures to adopt healthy lifestyles.

References

Arango-Lasprilla, J.C., Quijano, M.C. and Cuervo, M.T. (2010). Alteraciones Cognitivas, Emocionales y Comportamentales en pacientes con Trauma Craneoencefálico en Cali, Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 39 (4), 716-731.

Barman, A., Chatterjee, A. and Bhide, R. (2016). Cognitive Impairment and Rehabilitation Strategies After Traumatic Brain Injury. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38 (3), 172-81. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.183086.

Bombín-González, I., Cifuentes-Rodríguez, A., Climent-Martínez, G., Luna-Lario, P., Cardas-Ibáñez, J., Tirapu-Ustárroz, J. and Díaz-Orueta, U. (2014). Validez ecológica y entorno multitarea en la evaluación de las funciones ejecutivas. Revista Neurología, 59(2), 77-87.

Calderón, A., Cadavid-Ruiz, N. and Santos, O. (2016). Aproximación Práctica a la Rehabilitación de la Atención. Revista Neuropsicología, Neuropsiquiatría y Neurociencias, 16 (1), 69-89.

Carvajal-Castrillón, J., Henao, E., Uribe, C., Giraldo, M. and Lopera, F. (2009). Rehabilitación cognitiva en un caso de alteraciones neuropsicológicas y funcionales por Traumatismo Craneoencefálico severo. Revista Chilena de Neuropsicología, 4 (1), 52-63.

Corrigan, J.D, Selassie, A.W. and Orman, J.A. (2010). The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 25 (2), 72–80. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181ccc8b4.

Evald, L. (2015). Prospective memory rehabilitation using smartphones in patients with TBI: What do participants report? Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 25 (2), 283–297. doi:10.1080/09602011.2014.970557.

García-Molina, A., Enseñat-Cantallops, R., Sánchez-Carrión, R., Tormos, J.M. and Roig-Rovira, T. (2014). Rehabilitación de las Funciones Ejecutivas en el Traumatismo Craneoencefálico: Abriendo la Caja Negra. Revista Neuropsicología, Neuropsiquiatría y Neurociencias, 14 (3), 61-76.

García-Rudolpht, A. and Giber, K. (2015). A Data Mining Approach for Visual and Analytical Identification of Neurorehabilitation Ranges in Traumatic Brain Injury Cognitive Rehabilitation. Abstract and Applied Analysis, 1-14.doi:10.1155/2015/823562.

González, M., Pueyo, R. and Serra, J. (2004). Secuelas neuropsicológicas de los traumatismos craneoencefálicos. Anales de Psicología, 20, 303-316.

Hoffmann, M., Lefering, R., Rueger, J.M., Kolb, J.P., Izbicki, J.R., Ruecker, A.H., …Lehmann, W. (2012). Pupil evaluation in addition to Glasgow Coma Scale components in prediction of traumatic brain injury and mortality. British Journal of Surgery, 99, 122-130. doi:10.1002/bjs.7707.

Kolb, B. and Whishaw, L.Q. (2014). An introduction to brain and behavior.New York, N.Y.: Worth Publishers.

León-Carrión, J. (1995). Manual de Neuropsicología Humana. Madrid: Siglo XXI de España Editores.

Menon, D.K., Schwab, K., Wright, D.W. and Maas, A. (2010). Position statement: definition of traumatic brain injury.Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 91(11), 1637-40. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.05.017.

Muñana-Rodríguez, J. E. and Ramírez-Elías, A. (2013). Escala de coma de Glasgow: origen, análisis y uso apropiado. Enfermería Universitaria, 11(1), 24-35. doi:10.1016/S1665-7063.

More references

Park, HY., Maitra, K. and Martínez, K.M. (2015). The Effect of Occupation-based Cognitive Rehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injury: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. OccupationalTherapy International, 22, 104-116. doi:10.1002/oti.1389.

Poca, M. (2006). Actualizaciones sobre la fisiopatología, diagnóstico y tratamiento en los traumatismos craneoencefálicos. Retrieved from http://www.academia.cat/societats/dolor/arxius/tce.PDF.

Ríos, M., Muñoz, J. and Paúl-Lapedriza, N. (2007). Alteraciones de la atención tras daño cerebral traumático: evaluación y rehabilitación. Revista de Neurología, 44, 291-297.

Santacruz, L.F. and Herrera, A.M (2006). Trauma Craneoencefálico. Retrieved from http://salamandra.edu.co/CongresoPHTLS2014/Trauma%20Craneoencef%E1lico.pdf

Santana, L., Yukie, C., Alves, S., Costa, A.L., Pérez, J., Moura, L., … Silva, W. (2015). Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) for the cognitive rehabilitation of traumatic brain injury (TBI) victims: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BioMed Central, 16 (440), 1-7. doi:10.1186/s13063-015-0944-2.

Tate, R.L., Aird, V., and Taylor, C. (2013). Bringing Single-case Methodology into the Clinic to Enhance Evidence-based Practices. Brain Impairment,13 (3), 347–359. doi:10.1017/BrImp.2012.32.

Tirapu-Ustárroz, J., Cordero-Andrés, P., Luna-Lario, P. and Hernáez-Goñi, P. (2017). Propuesta de un modelo de funciones ejecutivas basado en análisis factoriales. Revista de Neurología, 64 (2), 75-84.

Tirapu-Ustárroz, J., García-Molina, A., Luna-Lario, P., Verdejo-García, A. and Rios-Lago, M. (2012). Corteza prefrontal, funciones ejecutivas y regulación de la conducta. En J. Tirapu-Ustárroz, A.G. Molina, M. Ríos-Lago y A.A. Ardila (Eds.), Neuropsicología de la corteza prefrontal y las funciones ejecutivas (pp. 87-120). Barcelona: Viguera.

Tsaousides, T., D’Antonio, E., Varbanova, V. and Spielman, L. (2014). Delivering group treatment via videoconference to individuals with traumatic brain injury: A feasibility study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 24 (5), 784–803. doi:10.1080/09602011.2014.907186.

VanHeugten, C., Gregório, G.W. and Wade, D. (2012). Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation after acquired brain injury: A systematic review of content of treatment. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 22 (5), 653–673. doi:10.1080/09602011.2012.680891.

If you liked this post, you might also be interested in:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Traumatismo craneoencefálico y su rehabilitación neuropsicológica en funciones ejecutivas

Aura Foundation explains the importance of cognitive stimulation in people with intellectual disability

Aura Foundation explains the importance of cognitive stimulation in people with intellectual disability

Leave a Reply