The Psychology and Quality of Life Research Group explains the neuropsychological consequences of COVID-19.

Lockdown, the flagship measure of the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has enormously affected the life of our society since it broke out in January 2020, whose consequences (sometimes referred to as COVID consequences) represent a true global public health emergency and a social humanitarian crisis (World Health Organization – WHO, 2020).

After the outbreak of the disease, most countries adopted social distancing through lockdown (Gharebaghi et al., 2020), and most areas of everyday life were affected, physically, psychologically, economically, socially and culturally.

Lockdown in Spain

In Spain, the declaration of a state of alarm by the Government just two months after the disease spread throughout the country, on March 14, gave rise to a lockdown that lasted until June 21. This lockdown is considered one of the strictest lockdowns in Europe during the COVID-19 crisis (Hale, 2021), allowing citizens to go outside exclusively to obtain essential supplies, work or receive medical treatment.

Later, in October of the same year, the second wave of COVID-19 infections occurred and a second state of alarm was reestablished. This time, the lockdown was less strict and consisted of a nightly curfew, movement restrictions and a restriction on gatherings of more than 6 people (Linde, 2020). This second lockdown lasted around 6 months.

The neuropsychological consequences of COVID-19

The purpose of the lockdown was nothing other than to control the transmission of the disease, reduce the number of infected citizens, protect the health system and reduce the number of deaths.

Although it was a success in containing and reducing the number of deaths, this measure in response to COVID-19 had negative economic, political and social consequences (Camera and Gioffré, 2021).

A relevant aspect within the study of COVID-19 consequences is the enormous psychological impact, through the increase in stress, anxiety and depression, associated with these lockdowns (Puig-Pérez et al., 2022).

In this context, it has been shown that social isolation could have negatively affected cognition (Lara et al., 2019), as well as the resulting anxiety, this being one of the flagship consequences of COVID-19.

Human beings are social by nature, which makes contact with other members of their species indispensable. A psychological condition that is strongly associated with social isolation is loneliness (Ge et al., 2017), the mental state in which someone has the perception of being socially isolated.

Both loneliness and social isolation can lead to similar health risks, the clearest indicator being that both significantly increase the risk of premature death from cerebrovascular disease (Alcaraz et al., 2018). This is really important, since social isolation and, therefore, loneliness, are included among the consequences associated with COVID-19.

Nonfunctional stress

Furthermore, it has been shown that extreme social isolation can cause a nonfunctional stress response in the organism (Valtorta et al., 2016). Stress is a psychophysiological response that prepares our organism to face a threat.

In the context of COVID-19 and its consequences, it should be highlighted that a large part of the Spanish population evaluated the first wave of COVID-19 as a very serious threat that caused a significant increase in anxiety as a consequence (Flor-Arasil et al., 2021; Rodríguez-Rey et al., 2020).

For example, it has been observed that high levels of state anxiety during the pandemic caused, in some cases, symptoms associated with Generalized Anxiety Disorder, a persistent worry about everyday things (Huang et al., 2020).

COVID-19 consequences on executive function and its components

There is scientific evidence indicating that social isolation as a consequence of COVID-19 could have an effect on decision-making. Before reviewing the studies conducted to date, the concept of executive function must be defined.

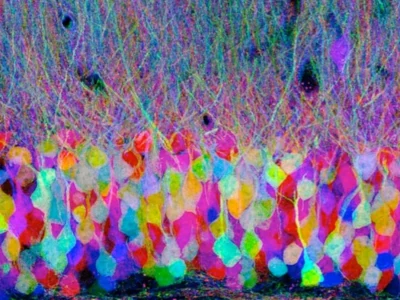

Executive function is composed of a set of skills involved in the generation, monitoring, regulation, execution and readjustment of behaviors that guarantee survival (Gilbert and Burgess, 2008).

These mechanisms are able to relate content coming from different input (sensory), processing (attention, memory, motivation and emotion) and output (motor) systems of information; with decision-making being a fundamental component.

Decision-making

Decision-making is the cognitive processing carried out by a person when they find themselves in a situation in which they must evaluate one or more characteristics, in order to determine which of the alternatives meets their expectations, goals or interests, from which a reflective process or a behavior to be followed is derived (Wang, 2008).

Working memory

In turn, another essential executive process for managing daily life is working memory. It is a system for storing information with limited capacity, in amount and duration, used to perform cognitive tasks, being continuously updated by our brain (Cowan, 2014).

Both executive components, working memory and decision-making are mandatory in everyday life, and consequently, have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, being neuropsychological consequences of it.

Research findings on the neuropsychological consequences of COVID-19

Impairs financial decision-making

In studies conducted on these neuropsychological consequences of COVID-19, it is shown that loneliness impairs financial decision-making due to the decrease in global cognition and specifically working memory (Stewart et al., 2020).

Similarly, in the study by Zhu and Wang (2017) the relationship between loneliness and risk in decision-making was explored. The main results indicate that higher levels of loneliness predicted a tendency to avoid risks in scenarios of monetary gains.

It affects working memory

On the other hand, numerous authors consider that the anxiety associated with social isolation as a consequence of COVID-19 acts as the basis of cognitive deficits, especially in the area of working memory, in line with what Moran (2016) reflects in his meta-analysis.

Specifically, this presents a predictive model in which worry symptoms and arousal symptoms anticipate poor cognitive performance, especially if the tasks employ phonological and spatial stimuli.

According to these pre-pandemic hypotheses, two more recent studies corroborate that high levels of anxiety as a consequence of COVID are associated with worse performance on tasks that measure working memory (Malesza and Kaczmarek, 2021).

Research project

Taking these results into account, a group of researchers from European universities (VIU, Universidad de Tilburg, Universidad de Gante, Eindhoven University of Technology, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Universidad de Zaragoza, Universidad de Montpellier and Universidad Silesia de Katowice) and Latin American (Universidad Nacional del Rosario), led by Prof. Barbara Kozusznik of the University of Silesia in Katowice and by Dr. Sara Puiz Pérez of the International University of Valencia in Spain, have developed a research project on the neuropsychological consequences associated with COVID with the aim of identifying intervention targets for the alterations produced.

Research objective

With data from studies like this it is hoped to determine which psychological and neuropsychological profile is associated with lockdown during the pandemic. The objective is to accelerate the emergence of specific neuropsychological protocols for this type of population.

References

- Alcaraz, K. I., Eddens, K. S., Blase, J. L., Diver, W. R., Patel, A. V., Teras, L. R., Stevens, V. L., Jacobs, E. J., & Gapstur, S. M. (2019). Social isolation and mortality in US black and white men and women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 188, 102-109. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30325407/

- Camera, G., & Gioffré, A. (2021). The economic impact of lockdowns: A theoretical assessment. Journal of Mathematical Economics, 97(1). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304406821001154

- Cowan N. (2014). Working Memory Underpins Cognitive Development, Learning, and Education. Educational psychology review, 26(2), 197–223. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4207727/

- Flor-Arasil, P., Rosel, J. F., Ferrer, E., Barrós-Loscertales, A., & Machancoses, F. H. (2021). Longitudinal effects of distress and its management during COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35002862/

- Ge, L., Yap, C. W., Ong, R., & Heng, B. H. (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and their relationships with depressive symptoms: A population-based study. PLoS ONE, 12(8), e0182145. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28832594/

- Gharebaghi, R., Desuatels, J., Moshirfar, M., Parvizi, M., Daryabari, S. H., & Heidary, F. (2020). COVID-19: preliminary clinical guidelines for ophthalmology practices. Medical Hypothesis, Discovery and Innovation in Ophthalmology, 9(2), 149. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7141793/

- Gilbert, S.J., Burgess, P.W., 2008. Executive function. Curr. Biol. 18(3), R110-R114. https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(07)02367-6?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0960982207023676%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

- Hale, T., Angrist, N., Goldszmidt, R., Kira, B., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., Webster, S., Cameron-Blake, E., Hallas, L., Majumdar, S., and Tatlow, H. (2021). A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nature Human Behaviour. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-021-01079-8

- Hawkley, L. C., & Capitanio, J. (2015). Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: a life span approach. Philosophical Transactions B, 370. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2014.0114

- Huang, J. Z., Han, M. F., Luo, T. D., Ren, A. K., & Zhou, X. P. (2020). Mental health survey of medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19. Zhonghua lao dong wei sheng zhi ye bing za zhi= Zhonghua laodong weisheng zhiyebing zazhi= Chinese journal of industrial hygiene and occupational diseases, 38(3), 192-195. https://search.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/resource/en/covidwho-32470

More references

- Lara, E., Caballero, F. F., Rico-Uribe, L. A., Olaya, B., Haro, J. M., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., & Miret, M. (2019). Are loneliness and social isolation associated with cognitive decline? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(11), 1613-1622. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31304639/

- Linde, P. (2020, 31, December). The year that Spain had to leave the hugs behind. El Pais. Retrieved 24 January, from https://english.elpais.com/society/2020-12-31/the-year-that-spain-had-to-leave-the-hugs-behind.html

- Lukasik, K. M., Waris, O., Soveri, A., Lehtonen, M., & Laine, M. (2019). The relationship of anxiety and stress with working memory performance in a large non-depressed sample. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6351483/#:~:text=We%20found%20a%20trend%20for,in%20anxiety%20and%20everyday%20stress.

- Malesza, M., & Kaczmarek, M. C. (2021). Predictors of anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. Personality and individual differences, 170, 110419. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342701180_PUBLISHED_Predictors_of_anxiety_during_the_COVID-19_pandemic_in_Poland

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020, Feb 19). Opening remarks by the WHO Director-General at the mission briefing on COVID-19. https://www.who.int/es/dg/speeches/detail/who-directorgeneral-s-opening-remarks-at-themission-briefing-on-covid-19

- Puig-Pérez, S., Cano-López, I., Martínez, P., Kozusznik, M. W., Alacreu-Crespo, A., Pulopulos, M. M., Duque, A., Almela, M., Aliño, M., García-Rubio, M. J., Pollak, A., & Kożusznik, B. (2022). Optimism as a protective factor against the psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic through its effects on perceived stress and infection stress anticipation. Current Psychology. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35313448/

- Rodríguez-Rey, R., Garrido-Hernansaiz, H., & Collado, S. (2020). Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic among the general population in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(1). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32655463/

- Stewart, C. C., Yu, L., Glover, C. M., Mottola, G., Bennet, D. A., Wilson, R. S., & Boyle, P. A. (2020). Loneliness interacts with cognition in relation to healthcare and financial decision making among community-dwelling older adults. Gerontologist, 60(8), 1476-1484. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32574350/

- Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S., & Hanratty, B. (2016). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart, 102(13), 1009-1016. https://heart.bmj.com/content/102/13/1009

- Verdejo-García, A., Bechara, A., 2010. Neuropsychology of executive functions. Psicothema, 22(2), 227-235. http://www.psicothema.com/pdf/3720.pdf

- Wang, X., 2008. Decision making in recurrent neuronal circuits. Neuron, 60, 215-234. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2710297/

- Zhu, Y., & Wang, C. (2017). The lonelier, the more conservative? A research about loneliness and risky decision-making. Psychology, 8(10), 1570-1585. https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation.aspx?paperid=78680

If you liked this article on the neuropsychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, you might also be interested in these articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Consecuencias neuropsicológicas del COVID-19

Worksheet for teaching emotional intelligence to children: Which photo best fits the word?

Worksheet for teaching emotional intelligence to children: Which photo best fits the word?

Leave a Reply