A distinction we commonly make when talking about the different human memory systems is the one referring to working memory and short-term memory.

In the literature on the subject we find authors who consider short-term memory to be a subset of working memory. On the other hand, there are those who consider the inverse relationship. Likewise, there are others who use both terms interchangeably, understanding that they are actually the same memory system, without a consensus that closes the theoretical debate [1].

In the clinical field, however, we usually make an explicit distinction between short-term memory span tests (or simple span — for example “Digits in forward order” from the WAIS-IV) and working memory span tests (or complex span — for example “Digits in reverse order” or “Digits in ascending order” from the WAIS-IV).

So what do we mean by short-term memory and working memory? What differences are there between them?

Defining memories: working memory and short-term memory

While the concept of short-term memory emphasizes the time of storage, and the brief period during which information remains active (30–40 seconds) [2], the concept of working memory or operative memory highlights the role of memory as a system for controlling information processing [1]. The latter is defined as the memory system that temporarily maintains and manipulates information, intervening in more complex cognitive processes such as language comprehension, reading, or reasoning [2, 3].

Therefore, although both types of memory are characterized by a short duration of storage and activation of information in consciousness, working memory adds manipulation to that information. That is, it transforms it by constructing relationships between the different data it handles, as well as integrating them with information stored in long-term memory. Thus, as we said, it enables important cognitive processes such as language comprehension and reasoning.

Updating Baddeley’s model

Probably the most widely disseminated model of working memory today is the one Baddeley proposed in 2000.

As we recall, this model was composed of a central executive system (SEC) and 3 subordinate components that process information of different modalities: the visuospatial sketchpad, phonological loop, and episodic buffer [2].

The phonological loop:

It is the system that temporarily stores information in verbal format; information that it keeps active through articulatory rehearsal. That is, using subvocal speech: the orofacial musculature moves during rehearsal of the information, just as if the words were being repeated aloud, but without producing any actual voice [2, 3].

The typical example usually given to better understand this component is that of a person who has just been told a multi-digit number (a code, for example) and, until they find a place to write it down, they repeat it subvocally so they don’t forget it. If someone distracts them before they write it down, this rehearsal is interrupted and it is likely that the person no longer remembers the number.

The phonological loop is relevant for transient verbal storage, for example, for reading and for maintaining the inner speech that is implicated in short-term memory [3]

The visuospatial sketchpad:

It works with information in visual format. This system would be fed by images that it would temporarily maintain and manipulate, making it possible for us to create and use these images and to orient ourselves in space [2, 3].

The episodic buffer:

It simultaneously stores phonological information from the loop and visuospatial information from the sketchpad. It also integrates it with long-term memory information, giving rise to a multimodal representation of the present situation. [3]

The central executive system (SEC) or supervisory attentional system (SAS):

It is a higher-order system than the previous ones, which performs control, supervision, and strategy selection. Thus, with information coming from the three previous subcomponents, it detects novel situations in order to respond to them, activating executive processes of anticipation, planning, and monitoring.

Working memory A.K.A. operational attentional system:

Tirapu-Ustárroz and Muñoz-Céspedes[3] have emphasized that this last component of Baddeley’s model, the SEC or SAS, does not contain information in itself (it would not have the nature of a store) and they suggest that it performs 6 subprocesses related to executive functions and that are interrelated:

- Encoding/maintenance of information when the capacity of the loop and the sketchpad is saturated.

- Maintenance/updating as the capacity of this system to hold and update information.

- Maintenance and manipulation of information.

- Dual execution: the ability to work simultaneously with the loop and the sketchpad.

- Inhibition as the capacity to suppress irrelevant stimuli of the Stroop paradigm type.

- Cognitive switching, which includes processes of maintenance, inhibition, and updating of cognitive sets or criteria.

In their review on the concept of working memory and its relationship with executive functions [3] they also suggest that the term working memory is inadequate. Since working memory actually has more to do with an attention system that works and operates on activated memory contents than with a provisional memory store. For this reason, they define it as “an operational attentional system to work with memory contents”.

Distinction between working memory and short-term memory

In addition to the distinctions noted above based on the definitions of working memory and short-term memory, differences between these two types of memory have been pointed out in relation to the different attentional demand they involve.

As has been pointed out [3,4], working memory is the system responsible for maintaining and manipulating information when the information to be maintained or the task to be performed is of such complexity that it saturates the cognitive system, so that short-term memory is insufficient.

The main distinction according to this is that engaging working memory poses a challenge to our attentional resources. So that in high cognitive load tasks, such as performing an activity while another distracting task is present, the subvocal rehearsal of the phonological loop is blocked by the attentional demand of the distracting task. This does not occur in a short-term memory task. For example, repeating digits in forward order.

Moreover, working memory tasks correlate positively with scores on intelligence tests and executive functions, which does not occur with scores obtained on short-term memory tests.

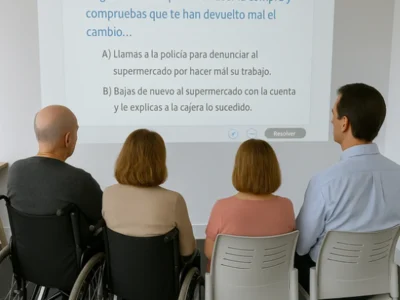

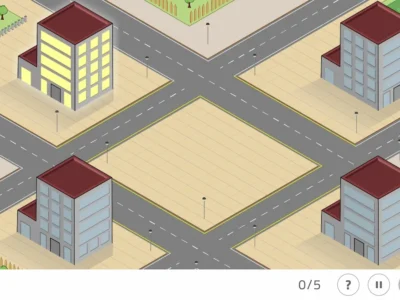

NeuronUP has prepared various exercises to work on different components of working memory, including verbal and visuospatial modalities. And also, specific exercises to train dual-execution processes. If you are a professional and want to try them, request a free trial of the platform.

Bibliography

- Ruiz-Vargas, J. M. (2010). Short-term memory. In: Manual de psicología de la memoria, pp. 147-179. Madrid: Síntesis.

- TirapuUstárroz, J. and Grandi, F. (2016). On working memory and declarative memory: proposal for a conceptual clarification. PanamericanJournal of Neuropsychology, 10 (3): 13-31.

- Tirapu-Ustárroz, J. and Muñoz-Céspedes, J.M. (2005). Memory and executive functions. Revista de Neurología, 41 (8): 475-484.

- Cowan, N. (2008). What are thedifferencesbetweenlong-term, short-term, and workingmemory? Progress in BrainReserarch, 169: 323-338.

If you liked this article about working memory and short-term memory, you may also be interested in:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Memoria de trabajo y memoria a corto plazo: definición y diferencias

Neuropsychological assessment in children with ADHD – Answering questions

Neuropsychological assessment in children with ADHD – Answering questions

Leave a Reply