In this article we address the relationship between attention and processing speed, analyzing whether they are part of the same cognitive process or whether they are distinct mechanisms.

Introduction

Attentional processes and processing speed constitute two cognitive elements of great relevance in current neuropsychology. They are closely related, so that, although they are distinguishable constructs, they are often addressed together.

In clinical practice and in everyday tasks both functions often operate interdependently, and it has been observed that a disturbance in either of these two areas has a marked impact on the other (Ríos et al., 2012; Salthouse, 2000). In addition, throughout history attentional mechanisms have been investigated with multiple experimental tasks, among which the use of tasks that measure reaction times stands out, making processes and measurement instruments, in some way, unified. These reasons may explain, at least partially, why the study of attention and processing speed have been closely related and addressed jointly.

However, some authors have pointed out that processing speed is an element of cognition that has its own entity and could be addressed specifically (Bessel, 1820; Donders, 1868; Kant, 1798; Muller, 1801; Ríos et al., 2004; Salthouse, 2000; Schneider and Schiffrin, 1977; Spikman et al, 2000; Von Helmholtz, 1821-1894). Currently, numerous findings indicate that processing speed, and its alteration, slowness of processing, constitutes a fundamental element for the diagnosis and treatment of nervous system disorders (DeLuca and Kalmar, 2008).

Attention and processing speed

What are attention and processing speed?

On the one hand, attention constitutes a complex set of processes or cognitive mechanisms aimed at maintaining a level of activation that allows the processing of information, and the orienting, selection and maintenance of processing on some stimuli and relevant actions (Posner and Petersen, 1990; Petersen and Posner, 2012). On the other hand, processing speed refers to the rate at which the brain receives, analyzes and produces responses to stimuli (Ríos and Periañez, 2010), which does not affect attention exclusively, but also the functioning of other processes such as memory, language, executive functions or social cognition.

These definitions make it possible to detect some differences between the two mechanisms.

Neuroanatomical bases of attention and processing speed

To this question should be added that the neuroanatomical substrate of each of them further influences the existence of important differences.

One of the most relevant models in the field of attention proposes the existence of three attentional networks:

- the alerting network (linked to general arousal and the maintenance of the vigilance state);

- the orienting network (responsible for orienting and shifting the attentional focus);

- and the executive network (involved in the supervision and control of attention).

These are related to cortico-subcortical structures that are reasonably well defined (Petersen and Posner, 2012; Dosenbach et al., 2024).

For its part, processing speed is related, in a global way, to the efficiency with which the brain transmits and transforms information. It has been proposed that a substantial part of processing speed depends on the integrity of the white matter and on the connectivity between brain regions (Martin-Bejarano, 2024; Vercruyssen; 1993).

Therefore, both functions are supported by distinct anatomical and physiological networks, and their alteration may be due to specific pathophysiological mechanisms.

Neuropsychological assessment of attention and processing speed

In the field of neuropsychological assessment this close interaction between attention and processing speed can also be observed. Many tests originally designed to evaluate different components of attention also require speed in responses.

The results obtained in tests such as the Trail Making Test (TMT) or the Stroop test have traditionally been interpreted in terms of impairments in specific attentional components. But these results are showing an overlap between processing speed deficits and attentional deficits. If a patient shows problems in attentional control, this may translate into an increase in their response time. At the same time, marked slowness in processing may be mistakenly interpreted as an attentional difficulty.

If these components are not adequately evaluated and separated there is a risk of establishing an incorrect therapeutic goal, with the consequent waste of time, effort and resources invested (for example, working on selective attention when the real problem was slowness in processing).

In this sense, having neuropsychological tests that help to correctly establish these dissociations is of great help. Some tests facilitate this task. Thus, for example, the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) or the processing speed index of the WAIS, or the calculation of derived scores in the TMT or the Stroop allow obtaining indices of processing speed relatively independent of the functioning of other cognitive mechanisms.

However, it is necessary to delve even further into the true causes of poor performance in tasks. Thus, the three-factor model of Costa et al., (2017) indicates that, within slowness in processing, it is also possible to distinguish whether the slowness is sensory, cognitive or motor. The neuropsychologist must have the ability and the caution to properly assess these elements. Having specific tests to adequately isolate the impairment of each component of processing will be of great help in defining the treatment program necessary for each patient.

Many neuropsychologists are aware of the need to make this separation, but the tools available today require added work on the part of professionals who, guided by available cognitive theories, must seek the existence of these dissociations. Therefore, neuropsychological assessment must evolve toward tests that isolate, as far as possible, each of these functions for a precise differential diagnosis (Arroyo et al., 2021; Lubrini et al., 2016; Lubrini et al., 2020).

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Rehabilitation and stimulation

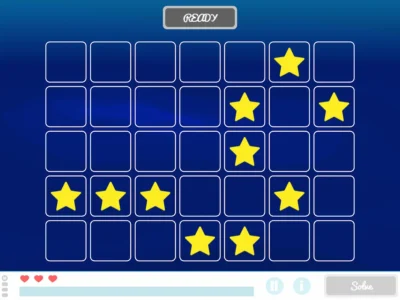

Finally, once the main cause of the patient’s difficulties has been detected, the selection of tasks that allow specific work on the affected component is necessary.

In this way, having separate exercises and intervention tools for the components of attention and for processing speed will greatly facilitate the clinician’s daily work.

An appropriate classification of rehabilitation activities should take into account the possibility of working on attentional components without time pressure, or introducing a speed component that requires a high execution pace.

On some occasions the presence of an attentional component will be desirable, or a combination of attention and speed, or even the presence of memory or executive function tasks, with high time pressure (which will facilitate the learning of strategies for managing this pressure more generally).

A rigorous treatment plan must consider specific tasks for each dimension while evaluating the mutual influence between both. When it is possible to clearly differentiate whether poor performance is predominantly due to an attentional deficit or to a global slowing, more precise and effective therapeutic interventions can be designed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, attentional mechanisms and processing speed, although close in their contribution to people’s behavior, are supported by partially differentiated neuroanatomical networks and demand equally differentiated assessment and intervention strategies. Properly understanding and evaluating each function is one of the keys to an accurate diagnosis, as well as to the implementation of effective rehabilitative interventions in the field of neuropsychology.

In the coming times we will observe how new technologies, the recent incorporation of AI and the high computational capacity available today greatly facilitate this differential diagnosis and the design of increasingly optimized programs for working on those affected components and, ultimately, predicting the evolution and functional prognosis of people who come to rehabilitation.

References

- Arroyo, A., Periáñez, J. A., Ríos-Lago, M., Lubrini, G., Andreo, J., Benito-León, J., Louis, E. D., & Romero, J. P. (2021). Components determining the slowness of information processing in parkinson’s disease. Brain and behavior, 11(3), e02031. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2031

- Costa, S. L., Genova, H. M., DeLuca, J., & Chiaravalloti, N. D. (2017). Information processing speed in multiple sclerosis: Past, present, and future. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England), 23(6), 772–789. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458516645869

- Donders, F. (1868–1869/1969). “Over de snelheid van psychische processen. onderzoekingen gedann in het physiologish laboratorium der utrechtsche hoogeshool,” in Attention and Performance, Vol. II, ed. W. G. Koster (Amsterdam: North-Holland).

- Dosenbach, Nico U. F., Marcus E. Raichle, and Evan M. Gordon. The brain’s cingulo-opercular action-mode network. PsyArXiv. 2024.

- John DeLuca, Jessica H. Kalmar (2008) Information Processing Speed in Clinical Populations. New York. Psychology Press

- Lubrini, G., Periáñez, J. A., Fernández-Fournier, M., Tallón Barranco, A., Díez-Tejedor, E., Frank García, A., & Ríos-Lago, M. (2020). Identifying Perceptual, Motor, and Cognitive Components Contributing to Slowness of Information Processing in Multiple Sclerosis with and without Depressive Symptoms. The Spanish journal of psychology, 23, e21. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2020.23

- Lubrini, G., Ríos Lago, M., Periañez, J. A., Tallón Barranco, A., De Dios, C., Fernández-Fournier, M., Diez Tejedor, E., & Frank García, A. (2016). The contribution of depressive symptoms to slowness of information processing in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England), 22(12), 1607–1615. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458516661047

- Martín-Bejarano, M (2024) Neuroanatomical correlates of information processing speed. Universidad de Cádiz.

- Petersen, S. E., & Posner, M. I. (2012). The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annual review of neuroscience, 35, 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150525

- Posner, M. I., & Petersen, S. E. (1990). The attention system of the human brain. Annual review of neuroscience, 13, 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000325

- Ríos-Lago, M., & Periáñez, J. A. (2010). Attention and speed of information processing. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience, Three-Volume Set, 1-3 (Vol. 1, pp. V1-109).

- Ríos, M., Periáñez, J. A., & Muñoz-Céspedes, J. M. (2004). Attentional control and slowness of information processing after severe traumatic brain injury. Brain injury, 18(3), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050310001617442

- Salthouse T. A. (2000). Aging and measures of processing speed. Biological psychology, 54(1-3), 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0301-0511(00)00052-1

- Spikman, J. M., van Zomeren, A. H., & Deelman, B. G. (1996). Deficits of attention after closed-head injury: slowness only?. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology, 18(5), 755–767. https://doi.org/10.1080/01688639608408298

- Schneider, W., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1977). Controlled and automatic human information processing: I. Detection, search, and attention. Psychological Review, 84(1), 1–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.1.1

- Vercruyssen, M. (1993) Slowing of behavior with age. In R Kastenbaum (Ed.). Enclyclopedia of adult development (pp 457-467). Phoenix Az. Oryx Press

If you liked this blog post about attention and processing speed, you will likely be interested in these NeuronUP articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Atención y velocidad de procesamiento: ¿Son parte del mismo proceso o son mecanismos diferenciados?

How NeuronUP powers cognitive stimulation in people with mental health challenges: Elkarkide Iturrama case study

How NeuronUP powers cognitive stimulation in people with mental health challenges: Elkarkide Iturrama case study

Leave a Reply