Neuropsychologist and researcher Ángel Martínez Nogueras explains in this article the Chiari malformation type I and presents a clinical case.

Before presenting the clinical case discussed here, I will briefly describe what Chiari malformation consists of.

What is Chiari malformation?

It is a malformation due to incomplete development of the posteroinferior portion of the skull base during the embryonic period, which can be accompanied by complications such as syringomyelia and hydrocephalus.

The most extreme form consists of herniation of structures from the lowest portion of the cerebellum, the cerebellar tonsils, and of the brainstem through the foramen magnum, so that some parts of the brain reach the spinal canal, enlarging and compressing it.

Chiari malformation type I

The Chiari malformation can be classified into 5 different types, of which type I is the most frequent (1).

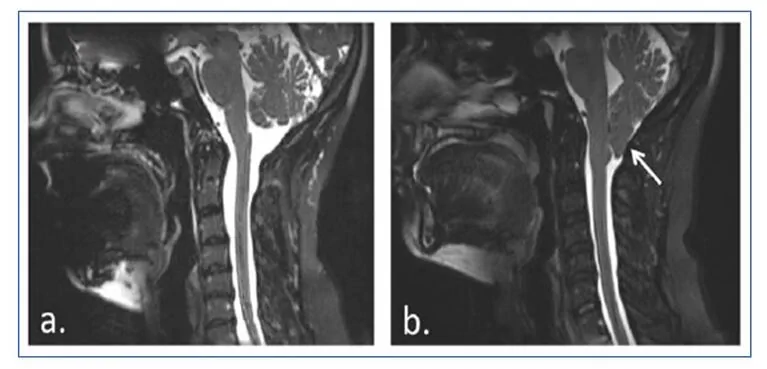

Chiari malformation type I involves a caudal herniation of the cerebellar tonsils of approximately 5 mm below the foramen magnum, which is not usually accompanied by descent of the brainstem or the fourth ventricle nor by hydrocephalus, but it is associated with syringomyelia.

Syringomyelia is caused by the formation of cavities or cysts (syrinx) filled with fluid within the spinal cord, which can slowly expand, causing progressive damage to the spinal cord and intracranial hypertension due to the pressure exerted by that fluid.

Symptoms of Chiari malformation

The symptoms associated with Chiari malformation can be numerous and varied, including motor deficits, emotional, cognitive, sensory, somatosensory and autonomic disturbances.

So as not to overextend this post I refer you to the attached bibliography where all possible symptoms and other details of Chiari can be reviewed. (2,3)

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Clinical case of Chiari malformation type I

Girl diagnosed with Chiari malformation type I, with syringomyelia, surgically operated on at 12 years of age.

After the surgical intervention she attended a neurorehabilitation center to receive specialized care. When we began the neurorehabilitation program she was 13 years old and in 2nd year of ESO, with specific educational support needs.

During the Press Conference and the taking of the medical history the following information was recorded:

- Sitting up was achieved at 6-7 months.

- Walking occurred at 18-20 months.

- Good language acquisition.

- The family reports that since birth they have seen her as clumsy from a motor point of view, both gross and fine motor skills.

- She falls often and has an unstable gait pattern.

- Manual tasks such as drawing, writing, coloring, tying shoelaces or putting toothpaste on the toothbrush are very difficult for her.

- Although school has always presented difficulties, she has never repeated a grade; nevertheless, she has needed support or adaptations for specific issues, such as giving her more time to complete daily tasks and exams, or taking some exams as multiple choice, due to difficulties with writing and handwriting.

- They also report that she is very easily distracted and needs continuous supervision to perform any task, such as dressing, brushing her teeth or preparing her school bag, and when she performs them she is extremely slow.

- She does not show behavioral problems at home or school that require special mention, beyond occasional tantrums or outbursts.

- However, the parents note the presence of self-directed behaviors such as biting or scratching herself until making wounds, but only during the school period; they remit during vacations.

- She presents difficulties in creating and maintaining social relationships, sometimes displaying an overly childlike attitude, and signs of certain immaturity inappropriate for her age.

Motor assessment

The motor assessment revealed a cerebellar syndrome with imbalance, inadequate tandem gait, head tremor, trunk ataxia with swaying, fine distal tremor, dysmetria and greater dystonic posture in the left hand.

Neuropsychological evaluation

Regarding the neuropsychological evaluation, after administering a comprehensive battery of tests the following was found:

- The girl was well oriented in time, place and person.

- Regarding attention processes, although a moderate deficit in sustained and selective attention was observed, the impairment of alternating attention stood out, together with a slowdown in information processing speed.

- With respect to executive functioning, she presented deficits in several subprocesses such as inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, planning, and goal-directed behavior control and supervision. Difficulty in problem solving, decision making and abstract reasoning was observed.

- She showed an adequate capacity for immediate memory, although this did not improve with repetition of the material to be remembered, that is, her learning capacity was reduced.

- An anterograde declarative memory deficit was observed both short- and long-term, with difficulties in fixation, consolidation and encoding of information, together with perseverations in free recall and in recognition of information. In part, this memory performance may be explained by deficits in attentional and executive processes.

- Regarding language, notable was the difficulty in reading comprehension, along with a reduced vocabulary and deficits in the formation and handling of verbal concepts.

- Finally, deficits in visuospatial skills, ideomotor, ideational and constructive apraxia, and difficulties in performing motor sequences and bimanual coordination were observed.

- In addition to all of the above, clear difficulties in the expression and recognition of emotions both of her own and of others were observed, along with a striking lack of empathy and social skills.

Improvements after one year of neuropsychological rehabilitation

After one year of neuropsychological rehabilitation, once a week, improvements have occurred in all cognitive functions, especially in memory and learning, where she performs at an appropriate level for her age.

This improvement was reflected in the girl’s school performance, gaining autonomy when studying at home and in performance on tasks and exams.

Can we explain cognitive deficits in patients with cerebellar involvement?

To conclude, and to try to make sense of this clinical case, can we explain cognitive deficits in patients with cerebellar involvement? Of course.

Although Chiari malformation is still considered a clinical entity that mainly presents with motor deficits, there are increasingly more scientific publications that confirm what we already suspected about this malformation, and about any pathology that affects the cerebellum, that is, that it very likely will present with cognitive deficits (4).

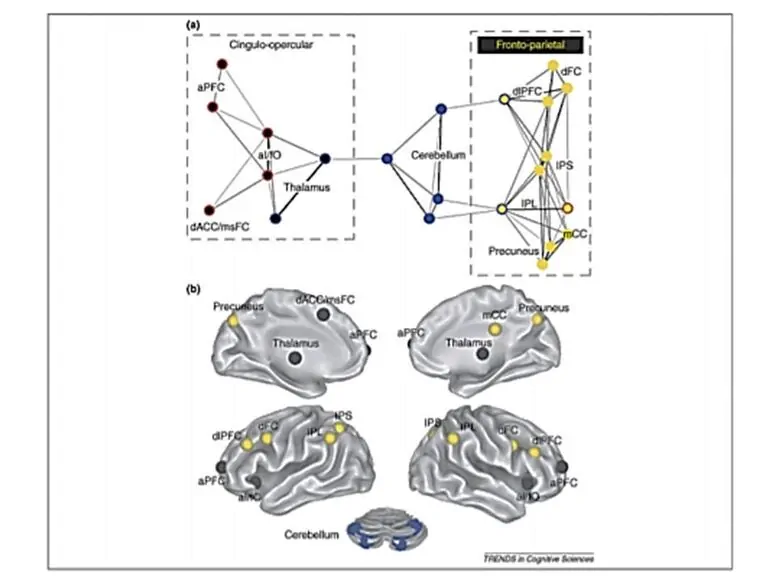

The available literature on the subject is clear. The cerebellum participates in multiple processes and functions such as attention, learning, memory, executive functions, visuospatial skills, language, and affective, behavioral and social regulation. I leave you a series of articles where the functions in which the cerebellum participates can be widely reviewed (5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18).

But not only does the cerebellum participate in cognitive processes, it is part of functional brain networks, which are the true basis of cognition (19). By way of example, I leave an image taken from an already classic article by Dosenbach and collaborators from 2008 (20), which very didactically shows how the cerebellum fits into functional brain networks of attentional or executive control.

We must take into account that the dominant current in contemporary neuroscience, and that we must transfer to our mindset as neuropsychologists, is that the brain works based on widely distributed, flexible and adaptable functional networks to the task at hand (21,22), where damage to one of its components can trigger dysfunction of the entire network (23).

Therefore, in light of all these data, we must abandon the traditional notion that led us to expect specific deficits associated with focal brain damage, and we must inevitably move toward a change of perspective in neuropsychological assessment and rehabilitation (24).

Bibliography

- Federación Española de Malformación de Chiari y Patologías Asociadas. DOSSIER MC (MALFORMACION de CHIARI). Available at:http://www.femacpa.com/index.asp?iden=11

- Documento de consenso. Malformaciones de la unión cráneo-cervical (Chiari tipo I y siringomielia). Available at:http://www.sen.es/pdf/2010/Consenso_Chiari_2010.pdf

- Federación Española de Malformación de Chiari y Patologías Asociadas. Guía práctica.Available at:http://www.femacpa.com/ficheros_noticias/boletin.compressed.pdf

- Rogers, J. M., Savage, G., &Stoodley, M. A. (2018). A Systematic Review of Cognition in Chiari I Malformation. Neuropsychology review, 1-12.

- Baillieux, H., De Smet, H. J., Paquier, P. F., De Deyn, P. P., &Mariën, P. (2008). Cerebellar neurocognition: insights into the bottom of the brain. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery, 110(8), 763-773.

- Kalron, A., Allali, G., & Achiron, A. (2018). Cerebellum and cognition in multiple sclerosis: the fall status matters. Journal of neurology, 265(4), 809-816.

- Baillieux, H., De Smet, H. J., Dobbeleir, A., Paquier, P. F., De Deyn, P. P., &Mariën, P. (2010). Cognitive and affective disturbances following focal cerebellar damage in adults: a neuropsychological and SPECT study. Cortex, 46(7), 869-879.

- Guell, X., Gabrieli, J. D., &Schmahmann, J. D. (2017). Embodied cognition and the cerebellum: perspectives from the dysmetria of thought and the universal cerebellar transform theories. Cortex.

- Van Overwalle, F., Baetens, K., Mariën, P., &Vandekerckhove, M. (2014). Social cognition and the cerebellum: a meta-analysis of over 350 fMRI studies. Neuroimage, 86, 554-572.

- Buckner, R. L. (2013). The cerebellum and cognitive function: 25 years of insight from anatomy and neuroimaging. Neuron, 80(3), 807-815.

- Sokolov, A. A., Miall, R. C., &Ivry, R. B. (2017). The cerebellum: adaptive prediction for movement and cognition. Trends in cognitive sciences, 21(5), 313-332.

- De Smet, H. J., Paquier, P., Verhoeven, J., &Mariën, P. (2013). The cerebellum: its role in language and related cognitive and affective functions. Brain and language, 127(3), 334-342.

- Timmann, D., Drepper, J., Frings, M., Maschke, M., Richter, S., Gerwig, M. E. E. A., & Kolb, F. P. (2010). The human cerebellum contributes to motor, emotional and cognitive associative learning. A review. Cortex, 46(7), 845-857.

- Leggio, M. G., Chiricozzi, F. R., Clausi, S., Tedesco, A. M., &Molinari, M. (2011). The neuropsychological profile of cerebellar damage: the sequencing hypothesis. cortex, 47(1), 137-144.

- Peterburs, J., & Desmond, J. E. (2016). The role of the human cerebellum in performance monitoring. Currentopinion in neurobiology, 40, 38-44.

- Tirapu Ustárroz, J., Luna Lario, P., Iglesias Fernández, M. D., & Hernáez Goñi, P. (2011). Contribución del cerebelo a los procesos cognitivos: avances actuales. Rev Neurol, 301-315.

- Hernáez-Goñi, P., Tirapu-Ustárroz, J., Iglesias-Fernández, L., & Luna-Lario, P. (2010). Participación del cerebelo en la regulación del afecto, la emoción y la conducta. Revista de neurología, 51(10), 597-609.

- Van Overwalle, F., &Mariën, P. (2016). Functional connectivity between the cerebrum and cerebellum in social cognition: a multi-study analysis. NeuroImage, 124, 248-255.

- Maestú, F., Quesney-Molina, F., Ortiz-Alonso, T., Campo, P., Fernández-Lucas, A., & Amo, C. (2003). Cognición y redes neurales: una nueva perspectiva desde la neuroimagen funcional. Rev Neurol, 37(10), 962-6.

- Dosenbach, N. U., Fair, D. A., Cohen, A. L., Schlaggar, B. L., & Petersen, S. E. (2008). A dual-networks architecture of top-down control. Trends in cognitive sciences, 12(3), 99-105.

- Pessoa, L. (2017). A network model of the emotional brain. Trends in cognitive sciences, 21(5), 357-371.

- van den Heuvel, M. P., & Pol, H. E. H. (2011). Exploración de la red cerebral: una revisión de la conectividad funcional en la RMf en estado de reposo. Psiquiatría biológica, 18(1), 28-41.

- Gratton, C., Nomura, E. M., Pérez, F., &D’Esposito, M. (2012). Focal brain lesions to critical locations cause widespread disruption of the modular organization of the brain. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 24(6), 1275-1285.

- Price, C. J. (2018). The Evolution of Cognitive Models: From Neuropsychology to Neuroimaging and back. Cortex.

If you liked this post about Chiari malformation, you will surely also be interested in reading the following post:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Malformación de Chiari tipo I. Caso clínico

Activities for Working on Theory of Mind with Children

Activities for Working on Theory of Mind with Children

Leave a Reply