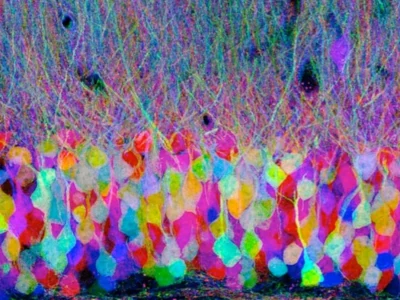

Do you know what social cognition is and how to work on it? In this article we explain what social cognition is and offer you social cognition exercises for children developed by NeuronUP under the principles of generalization.

What is social cognition?

Social cognition is the set of cognitive and emotional processes through which we interpret, analyze, remember, and use information about the social world.

Social cognition exercises for children

The social cognition materials we share below were developed by neuropsychologists and occupational therapists at NeuronUP for professionals who work with boys and girls.

Text reader

All of them include a text reader to make it easier for children and adolescents with reading difficulties to work on social cognition exercises for children; the texts can be listened to. With just the press of a button, you can hear the text on the screen read aloud.

Format

In addition, these social cognition materials for children can be used both in digital form and on paper.

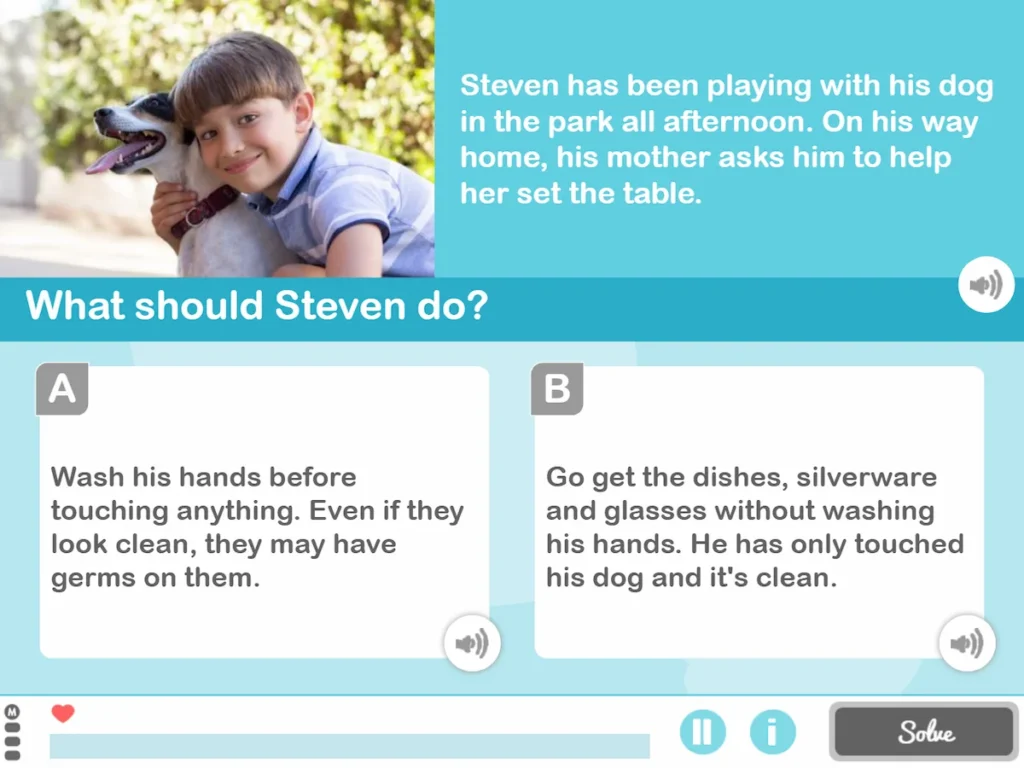

1. What is the best thing to do?

What does it involve?

This social cognition worksheet involves analyzing a situation and seeing what would be the correct way to behave in it.

The objective is for boys and girls to consider various situations they may encounter in their day and weigh the consequences that their decisions may have.

In the following video we show you an example of how to work with this exercise:

What does this activity target?

- Basic behaviors,

- hygiene habits,

- social relationships

- constructive criticism,

- empathy,

- assertiveness,

- civility,

- rights.

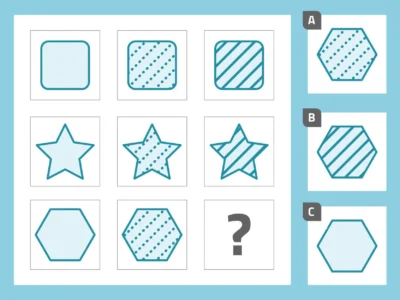

What is the best thing to do? is a worksheet and, like all NeuronUP worksheets, it is organized into five levels of difficulty:

Play by levels

- Basic,

- easy,

- medium,

- hard,

- advanced.

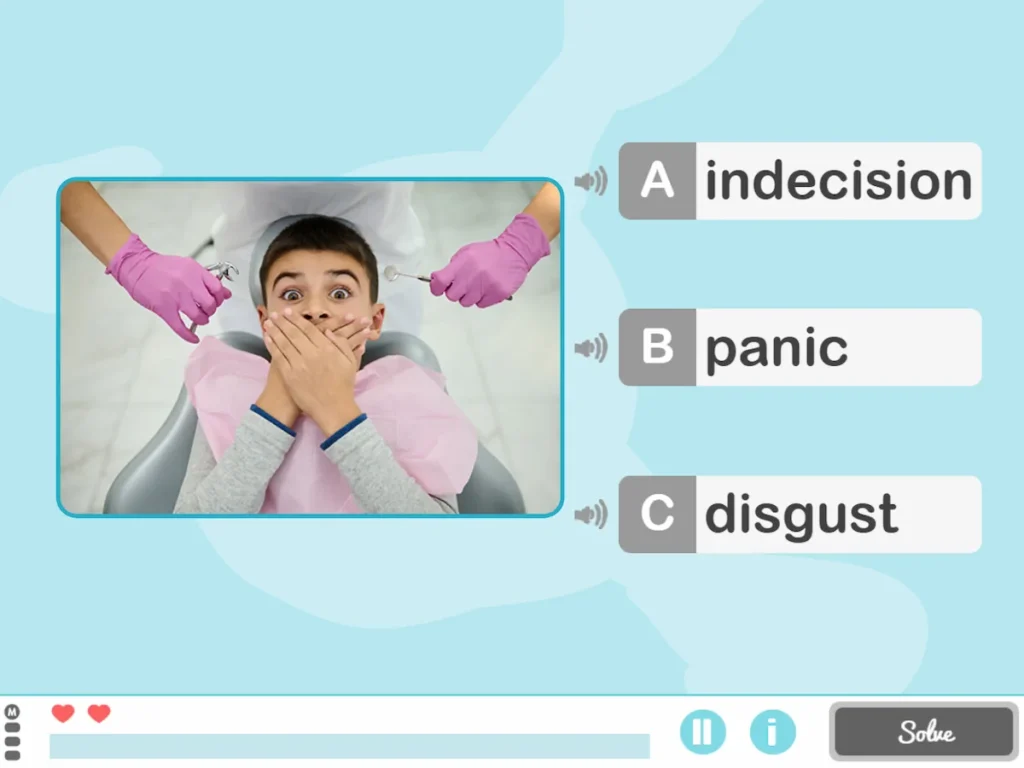

2. What are they feeling?

The second of the social cognition activities for children we present today is What are they feeling? It is an ideal activity for working on emotions with children!

What does it involve?

Children must identify what kind of feeling the person shown in the photo has and analyze which words best fit the photos.

In the following image we show you an example of how to work with this exercise:

What does this activity work on?

- Social cognition,

- vocabulary. Children must be able to name emotional states in order to express them and make themselves understood by others.

Play by levels

Like the previous activity, What are they feeling? has five levels of difficulty:

- Basic,

- easy,

- medium,

- hard,

- advanced.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

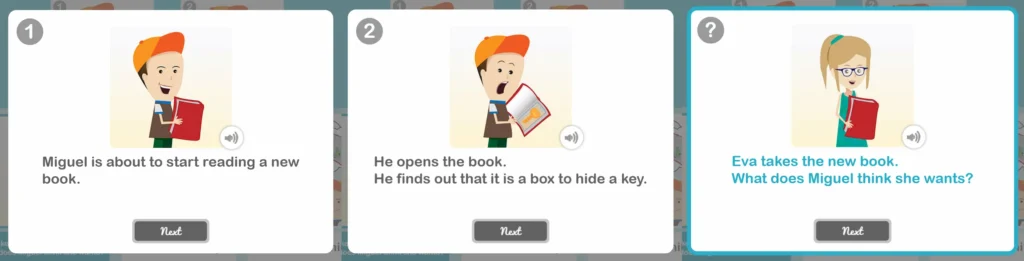

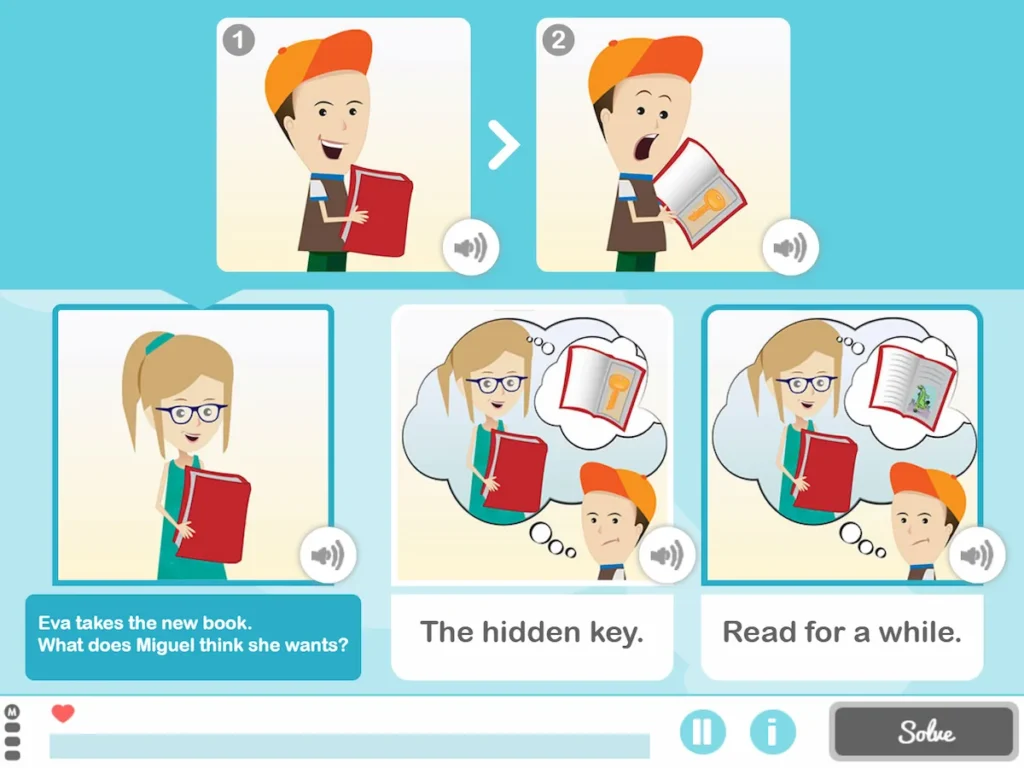

3. What do they Think?

What does it involve?

It is an activity to work on first-order false belief tasks.

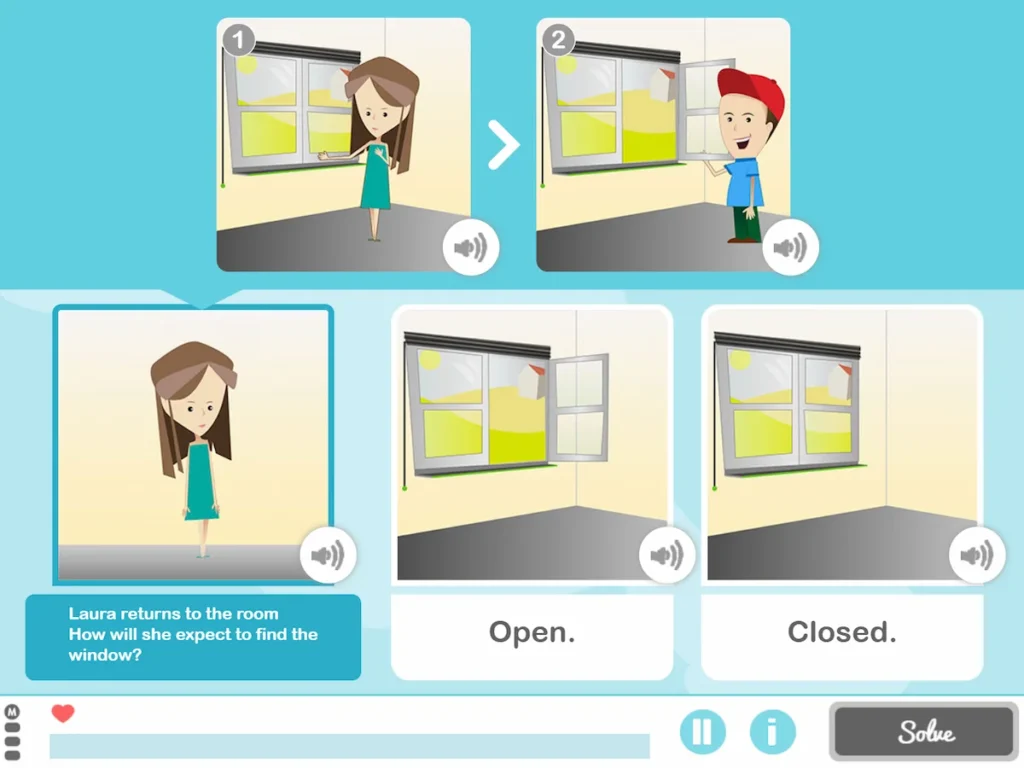

4. What do they expect to find?

What does it involve?

In this case, children work on unexpected content false belief tasks.

5. What do they think others think?

What does it involve?

The last of the social cognition exercises for children that we propose is What do they think others think? It is a worksheet of second-order false belief tasks.

Bibliography

- Burgess, P. W., Alderman, N., Forbes, C., Costello, A., M-A.coates, L., Dawson, D. R., … Channon, S. (2006). The case for the development and use of measures of executive function in experimental and clinical neuropsychology.Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 12(02), 194- 209.

- Wilson, B. (1987). Single-Case Experimental Designs in Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 9(5), 527-544. doi:10.1080/01688638708410767

If you liked these social cognition exercises for children, you may also be interested in this information:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Ejercicios de cognición social para niños

Social functioning in schizophrenia

Social functioning in schizophrenia

Leave a Reply