On the occasion of the International Awareness Day for Specific Language Disorder (TEL), speech therapist María Domingo explains Specific Language Disorder (TEL) and how they carry out their intervention with NeuronUP.

For six years we have included the use of NeuronUP in the treatment of Specific Language Disorder (TEL); since offering our patients an innovative, dynamic, ecologically valid, and customizable tool that helps them progress in their intervention is our priority.

Specific Language Disorder (TEL)

Specific Language Disorder (TEL) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects the acquisition and development of spoken language because it can alter the receptive area, the expressive area, or both.

Essentially, we can say there is a specific language disorder when the level of language skills affects the child’s ability to meet the social and educational expectations expected for their age.

It is classified as a heterogeneous disorder:

- First of all, we will never find two identical specific language disorders.

- Second, symptoms vary greatly from one child to another and do not always present in the same form and intensity.

Involvement of language components

Specific Language Disorder can involve one or several components of language: phonetic and phonological, semantic, morphosyntactic, or pragmatic.

- Phonetic/phonological area: in this area we often find children with unintelligible speech. Consequently, this implies phonological simplification errors, multiple speech-sound disorders, or difficulties in auditory discrimination.

- Semantic area: here we find children with a reduced vocabulary and difficulties accessing the lexicon; likewise, they know the words but have trouble retrieving them. For this reason, they often use very general words and circumlocutions. They also have many difficulties expressing and understanding anything abstract, anything that cannot be contextualized, and they struggle a lot to learn new vocabulary.

- Morphosyntactic area: this area is the most affected. They usually use simple sentences with few elements and poor structure with agreement errors, incorrectly conjugated verbs, omissions of prepositions or pronouns, among other errors. Clearly, if the morphosyntactic area is not affected, we cannot speak of a specific language disorder.

- Pragmatic area: it is always affected in people with TEL, since they have difficulty establishing social relationships through play, as well as understanding and respecting rules; likewise, they show difficulty understanding emotional states and solving interpersonal problems. Similarly, making inferences — that is, understanding anything that is not literal or contextualized such as irony, double meanings, metaphors, or jokes — is a major obstacle for them. Consequently, all this significantly shapes how they relate to others.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Warning signs in Specific Language Disorder

Between 0-12 months

- At 3–4 months presents a weak cry.

- At 3 months does not smile at familiar faces or voices.

- By the fourth month does not imitate or produce sounds.

- Does not orient toward sounds or the human voice at 5 months.

- At 8 months does not babble.

- Does not pay attention to repetitive interactive games.

- At 12 months does not use gestures such as waving goodbye or clapping.

Between 12-24 months

- Barely babbles.

- Shows little response to familiar names.

- Lack of communicative gestures.

- Does not point to show or request something.

- Does not respond to their name.

- At 18 months does not respond to “give me,” “look,” or “come.”

Between 2-3 years

- Does not use simple words.

- Is unable to name familiar objects or actions out of context.

- Does not understand simple commands.

- Unintelligible speech productions.

- Does not construct two-word phrases.

- Shows echolalic language as they repeat everything they are told.

- Shows lack of interaction with others.

- Their play is repetitive or restricted.

- Becomes frustrated in communicative situations.

Between 3-4 years

- Has difficulty producing 2-3 word phrases.

- Does not use adjectives or pronouns.

- Does not ask questions such as “what?” or “where?”

- Has difficulty expressing what they are doing.

- Does not understand sentences out of context.

- Has trouble finding the right word to express ideas or thoughts.

Between 4-5 years

- There are difficulties with pronunciation.

- Uses phrases of 3 words or fewer.

- Omits connectors, pronouns, verbs in sentences.

- Has a reduced vocabulary.

- Difficulty answering “what?” or “where?”

- Has trouble telling about lived experiences.

- Shows comprehension problems with long sentences or abstract meanings.

- Does not show interest in playing with other children.

Between 5-6 years

- Pronunciation difficulties persist.

- Has errors in sentence structure.

- Has difficulty answering question words.

- Difficulty understanding temporal and spatial concepts.

- Has difficulty with activities that require sustained periods of attention.

Causes of Specific Language Disorder

Although the prevalence of TEL is 2% and 7% of the child population, the cause of specific language disorder is unknown. However, there are findings that suggest a strong genetic link. For this reason, children with this disorder are more likely to have parents and siblings who have also had speech difficulties and delays. In fact, 50% to 70% of children with TEL have at least one family member with this disorder.

Research on Specific Language Disorder or TEL

The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, NIDCD, by its acronym in English, supports a wide variety of research aimed at understanding the genetic bases of TEL and the nature of the language deficits that cause it. Likewise, they seek to improve the diagnosis and treatment of children with the disorder.

Intervention for Specific Language Disorder

At the clinic we design an individual therapeutic plan based on the language profile presented by the child with TEL and their level of communication.

We focus treatment on the specific deficits that the patient with specific language disorder presents in terms of comprehension and their phonetic, semantic, morphosyntactic, or pragmatic skills. In addition, we analyze their environment and strive to ensure there is a language-friendly environment, advising communication guidelines in the family and school settings.

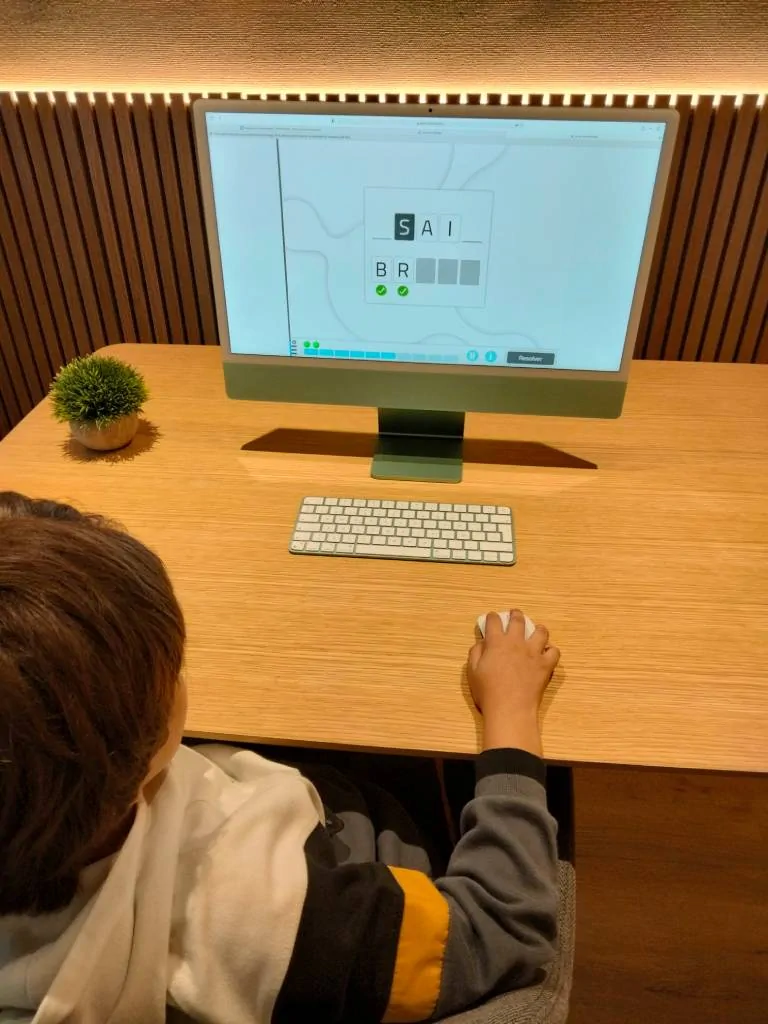

For six years we have included the use of the tool NeuronUP, to offer the possibility of working with our patients through in-person and online sessions, in a dynamic, interactive, ecologically valid and fully personalized way. Of course, stimulating the cognitive skills that help advance the intervention of patients with specific language disorder:

- Time Orientation.

- Executive functions.

- Memory.

- Attention.

- Social cognition.

- Language.

Conclusion

Experience shows us that consistency and maintaining the desire to learn allow great progress in our patients with Specific Language Disorder (TEL). For this reason, we chose a powerful working tool, innovative, versatile, and ecologically valid, NeuronUP.

If you enjoyed this post about Specific Language Disorder (TEL) and NeuronUP, you might be interested in these NeuronUP publications:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

El Trastorno Específico del Lenguaje (TEL) y NeuronUP

New auditory discrimination exercise for children

New auditory discrimination exercise for children

Leave a Reply