Clinical neuropsychologist at the European Center for Neuroscience, Loles Villalobos, explains in this article the use of dual-task activities and new technologies for neurorehabilitation in brain injury.

Performing neurorehabilitation activities that require the involvement of different processes allows for a more comprehensive approach that is closer to the reality of how our brain works and how it recovers after suffering a brain injury. Nowadays, new technologies allow us to carry out these integrated tasks effectively and in a motivating way for patients. As a result, we promote better outcomes in the rehabilitation process.

Brain injury and neurorehabilitation

Suffering a brain injury usually causes patients to experience impairment in different areas of functioning, the most common being those affecting the motor, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains (Wilson et al., 2017). Such impairment causes significant changes in their daily functioning, as well as that of their families (D’Ippolito et al., 2018).

Traditionally, in neurorehabilitation, each professional has intervened in their respective area. Often, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, neuropsychologists, etc., have carried out a coordinated and complementary but independent approach. However, the human brain works in an integrated way; the different processes operate interlinked—for example, any relatively complex motor activity requires adjusted cognitive performance to be carried out as efficiently as possible.

Thus, in daily life, we never perform an activity like walking in isolation; at the same time we think about where we are going, which way we should take, what we will do when we arrive, or even talk with our companion. Similarly, when doing an activity like cooking, we must stand, move around the kitchen, use our hands to manipulate food and utensils, and at the same time plan the different steps of the recipe, remember where the ingredients are, what step we have completed, what comes next, etc.

The dual-task paradigm

Common in our daily life, we must bring it into the field of neurorehabilitation for brain injury and include it in programs, activities, and procedures that integrate different processes. Based on this idea, for some years now, the use of the dual-task paradigm (Woollacott & Shumway-Cook, 2002), has been common in neurorehabilitation, in which the patient, within their rehabilitation activity, must perform several tasks simultaneously in a coordinated way, generally one with a motor component and another cognitive.

Adapting dual tasks to the profile of the patient with brain injury

In a patient who, after a brain injury, has difficulties walking properly, as well as attentional problems or various processes of executive functions, it is common to carry out activities in which, while the patient walks in a more or less complex environment (which can be modified sequentially), they are asked to perform cognitive tasks of varying demand, such as counting how many times the therapist makes a certain gesture or says a word, performing mental calculations, or talking on the phone. The use of these dual tasks within the rehabilitation program for patients with brain injury has proven to be effective (Kim et al., 2014; Park & Lee, 2019).

Sometimes we work with patients with severe impairment after brain injury, and one might think that using this type of task is not appropriate or is difficult to carry out. However, the possibility of adapting and adjusting these types of tasks is very broad. In fact, we have been able to use them with the majority of patients who have suffered a brain injury.

A case of brain injury after a traffic accident

Currently at the European Center for Neurosciences (CEN), an intensive neurorehabilitation center located in Madrid, we are working, for example, with a patient with brain injury who, after a very severe traffic accident, presents significant motor impairment (in addition to cognitive and emotional sequelae). The current objective at that level is for him to be able to stand with as little assistance as possible. However, because of the leg pain due to the severity of the injury he suffered, and the number of fractures and time of complete rest, this becomes a truly complex and difficult task for him.

Performing a simultaneous Cognitive Activity, in addition to the benefit of performing it, produces in this case a reorientation of attention toward that activity, less focus on the pain, and consequently a greater benefit in the standing motor exercise. Thus, for example, standing focused only on posture and elapsed time is possible for five or ten minutes; however, when performing a simultaneous Cognitive Activity, the patient with brain injury can remain standing and perform it effectively for more than half an hour.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Dual tasks and new technologies

New technologies are indispensable tools today in the approach to patients with brain injury. At CEN we have a large number of technological and robotic resources that help patients and allow them to progress in their rehabilitation process.

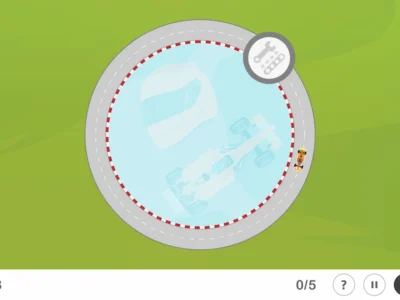

Returning to the patient with brain injury, he is not yet able to stand independently, bearing all his weight on his legs. The use of a device like the Rysen (the only system worldwide for 3D weight support, which allows addressing balance and gait) enables the device to support the desired percentage of his weight through a harness. This allows regulation of the support and gradual progress, achieving that the patient progressively supports more and more percentage of his weight. In this way, with the patient standing, we can introduce a second task of a cognitive nature adapted to his level of performance.

Cognitive and motor work with NeuronUP and Rysen

Moreover, at the center, we use NeuronUP with some patients who need training in certain affected cognitive processes. For some time now, we have also had a large touchscreen that allows for a better interaction of patients with it, greater immersion and motivation in its use, the use of both limbs with a greater range of motion, as well as carrying out standing work.

In the case mentioned, with the patient standing using the Rysen, we place the screen in front with NeuronUP activities adapted to his characteristics. For him, because of his cognitive sequelae due to the brain injury, it is important to work at a visual, attentional, and executive function level. In this sense, a very useful activity is “Plan Copy”. In it the patient must focus on a model layout with a series of boxes and reproduce it by placing the exact elements in each corresponding location.

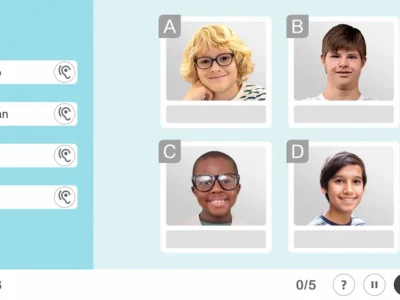

Likewise, if we want to introduce moving elements and increase the demand on more complex attentional processes as well as working memory, activities like “Bottle Caps” are very interesting and motivating for the patient with brain injury. In it a series of Bottle Caps with numbers move across the screen and the patient must find them and mark them from largest to smallest. Additionally, it allows us to work on monitoring and inhibitory control.

Another recently introduced and motivating activity for the patient is “Word Association”, in which they must match pairs of words by their semantic relationship. It allows us to work at a cognitive level on reasoning and at a motor level on the upper limb movement with a greater range of arm displacement, since they must drag the words across the screen while holding them pressed.

Conclusions

In this way, we have achieved that the patient with brain injury remains standing while performing activities for much longer periods than when no other activity was incorporated, making an attentional refocusing, with less attention to the pain and more to the external demand. Furthermore, it allows us to work on different motor and cognitive processes in an integrated manner, more similar to daily life activities.

The neurorehabilitation of patients who have suffered a brain injury is a field in constant advance and progress. The coordinated and integrated work of the different professionals involved who employ techniques and tools with proven scientific evidence, as well as the use of new technologies, allows us to develop individualized programs that substantially help the progress of patients.

References

D’Ippolito, M., Aloisi, M., Azicnuda, E., Silvestro, D., Giustini, M., Verni, F., Formisano, R., & Bivona, U. (2018). Changes in Caregivers Lifestyle after Severe Acquired Brain Injury: A Preliminary Investigation. BioMed Research International, 1, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2824081

Kim, G. Y., Han, M. R., & Lee, H. G. (2014). Effect of dual-task rehabilitative training on cognitive and motor function of stroke patients. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 26(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.26.1

Park, M. O., & Lee, S. H. (2019). Effect of a dual-task program with different cognitive tasks applied to stroke patients: A pilot randomized controlled trial. NeuroRehabilitation, 44(2), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-182563

Wilson, L., Stewart, W., Dams-O’Connor, K., Diaz-Arrastia, R., Horton, L., Menon, D. K., & Polinder, S. (2017). The chronic and evolving neurological consequences of traumatic brain injury. The Lancet Neurology, 16(10), 813–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30279-X

Woollacott, M & Shumway-Cook, A. (2002). Attention and the control of posture and gait: a review of an emerging area of research. Gait Posture, 16: 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6362(01)00156-4

If you enjoyed this post about neurorehabilitation in brain injury through the dual-task paradigm and the use of new technologies, you might be interested in these publications from NeuronUP:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Neurorrehabilitación en daño cerebral: tareas duales y nuevas tecnologías

ADHD Treatment with Neurofeedback

ADHD Treatment with Neurofeedback

Leave a Reply