On the occasion of International Epilepsy Day, Psychology student Cristian Francisco Liebanas Vega tells us in this article about the Clinical neuropsychology in pediatric epilepsy neurosurgery. Specifically, he explains what epilepsy is, the types and causes of epilepsy, the stages of the epileptic seizure and the epileptic syndromes that are associated with cognitive manifestations. In addition, Liebanas emphasizes the importance of neuropsychological assessment and neurorehabilitation in patients with epilepsy

Definition and clinical considerations of epilepsy

Epilepsy, like other neurodevelopmental disorders, is not a single pathological entity, and although the hallmark of epilepsy is recurrent seizures, in a significant proportion of children and adolescents it is associated with intellectual problems of cognition and behavior.

Seizures, epilepsy and epileptic syndrome

The common denominator of epilepsy is seizures. According to the International League Against Epilepsy (as of ILAE) a seizure is defined as “the transient occurrence of signs or symptoms due to excessive neuronal activity or synchronous activity in the brain”.

Types of epileptic seizures

Two basic types of epileptic seizures are distinguished:

1. Focal seizure

Localized excitability of cortical or subcortical origin that occurs within networks limited to one hemisphere, and it can be more localized or distributed.

Forms of manifestation

In this type of seizure consciousness may be preserved or altered and different forms of presentation may be observed:

- Onset with motor signs: may present motor automatisms. Different types of seizures can be distinguished, such as:

- Atonic seizures,

- clonic,

- hyperkinetic,

- myoclonic,

- tonic,

- Non-motor onset (automatisms).

- They may present manifestations of automatic function such as sweating, temperature changes, excessive salivation, etc.

- Sensory: tingling, sensations of heat or cold, strong odors, visual disturbances, or pain.

- Cognitive: difficulty with language or a specific cognitive function (aphasia, apraxia or neglect)

- Memory lapses, feeling of Déjà Vu, repetitive thoughts, hallucinations, among others.

- Emotional: intense reactions unrelated to the situation, fear, aggressiveness, crying, abrupt changes (laughing-crying), etc.

2. Generalized seizure

Diffuse across the cortex. They originate at some point within neural networks distributed bilaterally and spread rapidly. These bilateral networks may include cortical and subcortical structures and be asymmetric (Berg et al., 2017).

They can present as:

- Motor: tonic-clonic (tonic and clonic), myoclonic, myoclonic-tonic-clonic, myoclonic-atonic,

- Non-motor: (absences): typical or atypical, myoclonic absence or with eyelid myoclonias.

When a seizure lasts longer than 60 minutes and does not remit with Medication, it is considered refractory status epilepticus. According to the ILAE (2017) this is a condition that can have long-term consequences, including neuronal damage or death and alteration of neuronal networks, depending on the type and duration of the convulsions.

Not all seizures are epileptic; there are many circumstances that can cause acute non-epileptic seizures. It is as important to recognize epileptic semiology as non-epileptic semiology. These can be non-epileptic paroxysmal disorders defined as cerebral dysfunction due to mechanisms different from epileptic seizures. These mechanisms can be:

- anoxic (breath-holding spasm),

- hypnic (night terror),

- psychogenic (anxiety attacks),

- stereotyped movements,

- pathological muscle contractions,

- muscle spasms,

- etc.

Epilepsy is defined as a brain disorder characterized by a persistent predisposition to generate epileptic seizures that has neurobiological, cognitive, psychological and social consequences.

Conceptually, epilepsy exists when the patient has had at least one unprovoked seizure and there is a high probability that a new seizure will occur. In this sense, the ILAE proposed in 2014 an operational clinical (practical) definition of epilepsy which is the one currently in use.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

4. Pharmacological treatment

The effects of antiepileptic drugs can have a positive influence on patients’ cognition and emotion by achieving control of epileptic seizures; however, by also acting on neuronal circuits that regulate cognition, they can produce undesirable neuropsychological effects.

Although currently the new antiepileptic drugs have a lesser effect on cognition, it is still evident in daily practice with these patients that there is a relationship between the drug’s effects and cognitive performance. The problems observed usually refer to specific cognitive deficits rather than a generalized cognitive dysfunction.

Monotherapy

Drug concentration levels in the blood are abnormally high or the rate of dose increase is too rapid (Álvarez- Carriles et al, 2011). Two medications with mild cognitive effects can potentiate each other or produce tolerability problems, leading to cognitive dysfunction (Moog, 2009).

The vast majority of these drugs decrease membrane excitability, increase postsynaptic inhibition or generally alter the synchronization of neural networks and consequently the reduction of neuronal excitability causes a significant decrease in processing speed and of control systems and maintenance of attention, these negative side effects can be as disabling or more disabling than the seizures themselves in developing brains.

General side effects caused by antiepileptic drugs

Although there are significant individual differences in response to treatment, we can establish some general side effects caused by different antiepileptic drugs such as:

- attentional and inhibitory disturbances, aggravated by the drowsiness caused by some antiepileptic drugs or by the insomnia produced by others;

- slowing of processing speed;

- irritability,

- motor restlessness;

- emotional dysregulation;

- impairment of working memory

- effects on the visual field,

- among others (Campos-Castelló and Campos-Soler, 2004).

More severe impairment is usually observed in those patients who have pharmacoresistant seizures, especially if these had an early age of onset, not only because they tend to have a longer chronic period of the disease, but also because they have tried a large number of treatments.

It is necessary to take into account patients’ drug doses and escalation times, since there is a relationship between dose increase and the increase in cognitive symptoms.

5. Brain plasticity

Brain plasticity and functional reorganization in pediatric epilepsy patients provide interesting and highly valuable data for understanding the idea that functions such as language or memory are flexible and modifiable especially during development.

The chronicity of the disease induced by an epileptogenic zone is associated with the recruitment of homologous areas of the contralateral hemisphere or interhemispheric regions that are not traditionally considered eloquent. They allow us during rehabilitation programs to use techniques to optimize or compensate functions—functional alterations that are slowly progressive can change functions such as language from the hemisphere classically understood as dominant (left) to the right, or can redirect language networks during development to non-traditional areas in the same hemisphere (Brazdil et al., 2005). But even so, we must always consider the capacity for functional reorganization as a unique and very complex individual process that requires intervention and follow-up by professionals specialized in the field of neuropsychological rehabilitation.

These are some of the factors that differ in each patient and influence the neuropsychological pattern; nevertheless, in epileptic pathologies there are cognitive functions that tend to be affected to a greater or lesser extent in most cases.

It is common to find involvement of subcortical features, either primarily produced by the abnormal paroxysmal activity or secondarily as a consequence of pharmacological treatment; or the combination of both, which is what we most frequently encounter.

That is, there is a primary subcortical involvement (attention maintenance, working memory, processing speed, Categorical Evocation) that is accentuated and significantly worsened with the use of certain drugs.

Clinical and neuropsychological manifestations observed in patients with epilepsy

Fundamentally the clinical and neuropsychological manifestations observed in patients with epilepsy affect attention, memory, language, processing speed, inhibition and working memory.

In the case of developmental epileptic encephalopathies there is greater overall involvement, both in cognitive and motor processes, so most patients will require interdisciplinary teams in the different contexts of intervention.

The symptomatology present in patients with epilepsy is often the same or similar to that of many neurodevelopmental disorders; therefore, when intervening and setting objectives to stimulate deficits or cognitive alterations, strategies used in other clinical conditions can be used, such as cognitive stimulation, optimization of other cognitive processes or compensation of the lost function.

The most important thing to consider when intervening with a child with epilepsy is the semiology of the seizure, as well as its evolution, since they will determine the cognitive profile and evolution.

Epilepsy occurs in other conditions

It should not be forgotten that epilepsy occurs in other conditions such as cerebral palsy, genetic syndromes, autism, etc., worsening the clinical manifestations of these cases, sometimes being the factor that causes neuropsychological regression.

It should be noted that any type of recurrent seizure affects cognitive functioning, including those labeled as benign childhood seizures. Most patients with benign childhood seizures do not usually manifest symptoms at the onset of seizures, but in the long term subtle symptoms of brain dysfunction begin to appear (mainly related to attention maintenance, working memory and inhibitory control processes). Therefore in these cases it is important to carry out evaluations.

Requirements of a neuropsychological rehabilitation program for epilepsy

Every neuropsychological rehabilitation program in epilepsy must meet the following requirements:

- Be based on theoretical reference models;

- adopt an interdisciplinary and multiple perspective, in the child’s different contexts (therapies, school, family, etc.);

- it is essential to establish an order of priorities;

- important to begin intervention early;

- use a sufficient treatment duration (depending on the case);

- preserved abilities are the basis of treatment;

- very important to consider emotional and motivational variables;

- have good family support.

The importance of neurorehabilitation in patients with epilepsy

Considering all of the above, it should be noted that neurorehabilitation is important not only for cognitive stimulation and rehabilitation, but also for mapping the patient’s cognitive profile and the seizure pattern.

The neuropsychological treatment allows ongoing clinical follow-up of the patient’s evolution, enabling the neuropsychologist to know the semiology presented by each epileptic patient. It also allows identification of different clinical manifestations or changes in the seizure pattern, which may be due to multiple factors (modifications in pharmacological treatment, the patient’s emotional state, overstimulation, etc.).

Follow-up of the patient during neurorehabilitation sessions will allow the neuropsychologist to observe whether there is progressive cognitive deterioration and therefore evidence disease progression, as well as objectify the possible impairment of cognitive functions due to Medication.

This last aspect is important because if we are in contact with the medical team, the neuropsychologist’s observations can contribute to the choice of more effective drug doses that have fewer cognitive adverse effects for the patient.

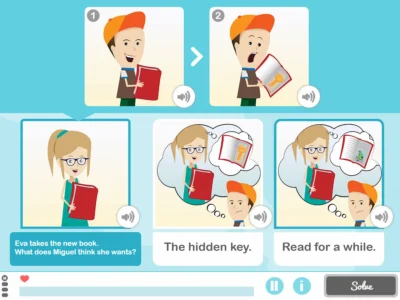

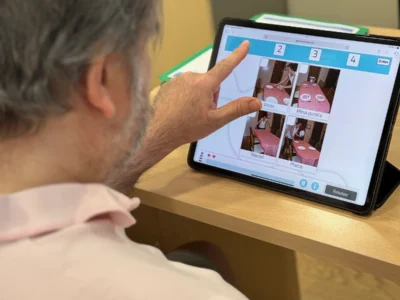

Finally, we want to emphasize that all programs (both computer-based and pencil-and-paper) are tools to work on the affected processes. They do not rehabilitate by mere application; the success of the program depends on the goal we have and the procedure used.

Cognitive processes cannot be understood as independent entities, especially in a network pathology such as epilepsy; the human cognitive system is based on the interaction of different neuropsychological processes, influencing one another both in their development and in their recovery; therefore, we must rule out the rehabilitation of specific functions.

If you liked this post about Clinical neuropsychology in pediatric epilepsy neurosurgery, you may also be interested in the following articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Neuropsicología clínica en la neurocirugía de la epilepsia pediátrica

A Brief Neuropsychology of Authoritarianism

A Brief Neuropsychology of Authoritarianism

Leave a Reply