Therapist José López explains the effect that intensive therapies have on the recovery of people after a brain injury.

For some years now the effect that intensive therapies have on recovery of people after a brain injury has begun to be studied more frequently. The results of these studies are beginning to show the enormous potential of intensive therapies in patient recovery, beyond what had been achieved until now through other forms of treatment.

Pioneers in this field of intensive therapies are Dr. Edward Taub and his team at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who developed in the 1990s, after several previous years of animal model studies, a treatment technique called constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT): Taub_1994_Shaping.pdf

Dr. Taub’s group designed a training program that, among many other things, was pioneering for the amount of time it devoted to working with patients, specifically 6 hours a day, for three consecutive weeks in their first protocol.

Dr. Taub and his team were clear from the outset, and later demonstrated through successive studies, that it is necessary to increase the work patients perform to optimize their rehabilitation and to achieve lasting structural changes in the brain. Of course, not only the number of hours per day that are dedicated is important, but also the content of those hours, although in this post I will focus more on the first aspect.

Repetition as the key to learning

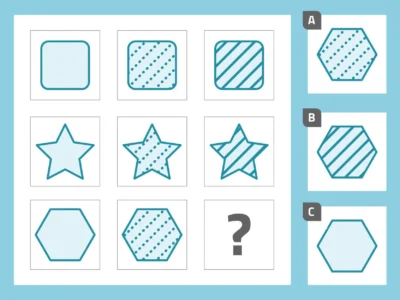

Other interventions from the point of view of physical rehabilitation have continued to be developed over the last two decades. Today the use of robotics and new technologies is increasingly common, with many studies carried out and in development. In this specific field, the main justification given for their usefulness lies in the increase in practice they provide compared to other interventions. You can increase the time the patient spends working and also the number of repetitions achieved with their use. It is therefore believed that repetition is one of the keys to learning.

While it is true that repetition is not the only important factor to promote learning, there is a consensus that we should practice what we want to learn as frequently as possible, to speed up the process, consolidate it, or acquire mastery of the task we perform.

For this reason, without needing to turn to studies or systematic reviews, we can find hundreds of examples in our daily lives that lead us to the same conclusion: learning to play an instrument, learning a language, learning a sport, or simply learning to move when we are born and being able to walk or develop appropriate motor, communication, or planning and problem-solving skills, to name just a few.

If we compare the time patients dedicate to their rehabilitation, the number of repetitions of movements they make, the communicative opportunities or opportunities to practice cognitive functions they have, with what would be necessary or advisable, we see there is a huge gap. In my experience, and increasingly the results of studies also point in this direction, many patients do not improve because they are not worked with enough, not all the potential their brains have is squeezed out.

Intensity is important when working on communication skills

From the rehabilitation of motor functions, following the same principles of intensity, repetitions, motivation, behavioral management, etc., Dr. Taub’s same study group developed an intensive therapy for language, which they called constraint-induced aphasia therapy (CIAT): https://www.uabmedicine.org/patient-care/treatments/ci-therapy

Also, through studies and implementation with many patients this technique is offering very promising results, showing that intensity is also important when working on communication skills.

The effect of exercise on cognitive functions

In recent years the effect that exercise has on cognitive functions has also been increasingly studied. In this 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis the effect of aerobic exercise, resistance training, multicomponent training and tai chi on various cognitive functions is discussed: http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/early/2017/03/30/bjsports-2016-096587

Aerobic training and resistance training, for example, are part of many intensive therapy programs, and beyond possible explanations of why physical training improves cognitive functions, we should ask ourselves a question:

How many training sessions are purely physical or purely cognitive?

In studies on intensive therapies such as those by Dr. Taub, cognitive aspects are not measured pre and post, but I am sure that in many patients we could also see changes in this regard, because the ultimate aim of Dr. Taub’s therapy, and what has been demonstrated in research results, is that the patient participates more in their activities of daily living, and after all, what are activities of daily living if not a bringing together of a person’s motor and cognitive skills?

The use of intensive therapy in the rehabilitation of cognitive functions in neurorehabilitation

There are studies on intensive cognitive therapy (cognitive behaviour therapy CBT) in phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorders and anxiety disorders: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20573292 , but I have found little about the use of intensive therapy in the rehabilitation of cognitive functions in neurorehabilitation.

I speak of cognitive functions in neurorehabilitation and not of neuropsychology because I believe that such functions are not exclusive to neuropsychology, although it is the discipline that has studied them most and works on them. I prefer the denomination of Ian H. Robertson and Susan M. Fitzpatrick in their publication “The future of cognitive rehabilitation”: https://www.jsmf.org/about/s/The%20future%20of%20cognitive%20neurorehabilitation.pdf , where cognitive rehabilitation is defined as “a structured and planned experience, derived from the understanding of brain function, that improves cognitive dysfunctions and brain processes caused by disease or injury, and that enhances function in daily life”.

For this reason, based on this definition, we will understand that we can be working on cognitive functions in any of the rehabilitation activities we carry out, without having to make a distinction between physical and cognitive therapies, between movement and cognition. Therefore all intensive therapies that emerged from the “motor field” have their influence on cognition, and the ability to direct this influence in a more specific way would only depend on our knowledge of how cognition works.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

The technique of “constraint induced movement therapy”

In the previously cited publication “The future of cognitive rehabilitation”, the authors cite Dr. Taub’s “constraint induced movement therapy” as an example of a “cognitive neuroscience approach” that meets the main criteria of cognitive neurorehabilitation:

- Cognitive neurorehabilitation methods should be represented in detailed protocols, with or without supporting technologies, that allow their replication in other studies.

- There should be at least one articulated theoretical and empirical model that supports the application of such a method or technique.

- Effective cognitive neurorehabilitation should be able to demonstrate changes in cognitive function and in brain function, measured with one or more imaging or associated methods.

- Cognitive neurorehabilitation should be able to demonstrate its effect on a person’s activities of daily living.

I believe it is the appropriate time for us to begin to consider what contribution cognitive neurorehabilitation can make in the field of intensive therapies in neurorehabilitation, a field that is increasingly booming and with very promising early results.

This contribution, from my point of view and experience, would be based on integrating therapies more and better, beginning to question the motor-cognitive dichotomy, to treat the person as a whole, the brain as a complex system that works by integrating diverse information and also responding through the joint and coordinated work of different systems. If the brain does it this way, we therapists should also approximate that as much as possible.

If you enjoyed this post about intensive therapies in neurorehabilitation, you may be interested in these NeuronUP articles.

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Terapias intensivas en neurorrehabilitación: ¿aplicable solo a las funciones motoras?

Autism and the Reality of People with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism and the Reality of People with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Leave a Reply