From childhood we acquire information about how to perform a given task unconsciously and through experience. This information is stored and consolidated in implicit procedural memory to be retrieved when we face that same task again. But, what happens when there is a deficit in this automatization process? Certainly, what occurs is that significant problems arise in acquiring perceptual-motor habits and cognitive strategies that are basic for a child’s development in everyday life. In this post, occupational therapist Loinaz Guridi and neuropsychologist Ramón Fernández de Bobadilla explain the rehabilitative treatment of developmental coordination disorder.

What is developmental coordination disorder?

Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) is a chronic and prevalent neurodevelopment condition that has a significant impact on a child’s ability to learn and to manage with ease, in addition to their school activities and those belonging to their daily life.

It is characterized by impairment in motor coordination and in cognitive and psychosocial skills. At first, it leads to subtle difficulties participating successfully in the tasks presented during the early years of life. But over time, and if not adequately addressed, it has a very problematic impact affecting multiple aspects.

The main concerns of families are usually about the secondary consequences of the lack of motor coordination. These include an increased risk of depression and childhood anxiety, the appearance of obesity and diminished self-esteem.

It is also considered a global learning disorder due to a delay in the automatization of information acquisition procedures, making successful academic performance difficult. It affects around 5-6% of school-age children, so it is recommended to begin treatment as early as possible in order to minimize the impact these difficulties have on the performance of the little ones.

Children with this disorder have significant limitations in their capacity for planning and motor control.

Problems associated with developmental coordination disorder

As a consequence, problems appear in multiple processes, among which the following stand out:

- Reduction of information processing speed,

- problems in the ability to generate beneficial strategies to achieve goals,

- deficit in the control of representation of actions,

- problems maintaining attention.

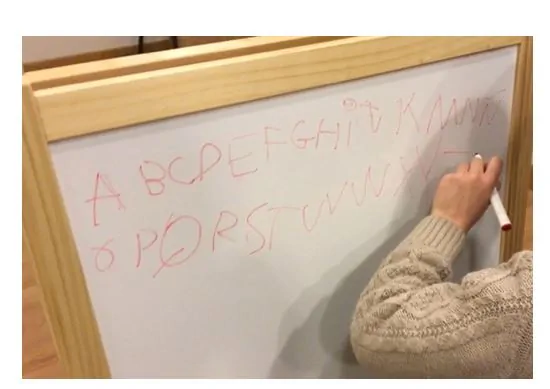

All of these, at the school level, are usually reflected in difficulty automatizing reading, writing or arithmetic, which in turn affects many other activities.

Characteristics of developmental coordination disorder

Indeed, the main characteristics are motor coordination disorder, school learning difficulties and social relationship problems.

Throughout the study of this disorder various denominations have been used that refer to very similar characteristics. Such as specific psychomotor development disorder, developmental dyspraxia, DAMP (attention deficit, motor control and perception deficit), right hemisphere syndrome and nonverbal learning disorder.

Also, in 2009 the research by Narbona, Crespo-Eguílaz and Magallón oriented this disorder under the name of procedural learning disorder (PLD). However, the diagnostic guidelines DSM-5 and ICD-11 (of international use and recent revision) recognize this set of symptoms as developmental coordination disorder.

Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of developmental coordination disorder

According to the DSM-5 the following clinical criteria must be met for its diagnosis:

| Developmental coordination disorder (DSM-5) |

|---|

| A. The acquisition and execution of motor coordination skills is substantially below what is expected for the individual’s chronological age and opportunities for learning and use of the skills. The difficulties manifest as clumsiness (e.g. dropping or bumping into objects), as well as slowness and poor accuracy in the performance of motor skills (e.g. catching objects, using scissors or cutlery, handwriting, riding a bicycle, or participating in sports). |

| B. The deficits in the motor skills of criterion A significantly and persistently interfere with activities of daily living as expected for the chronological age. For example, self-care. They also affect academic/school productivity, work activities, leisure and play. |

| C. The onset of symptoms is in the early developmental period. |

| D. The motor skill deficiencies are not better explained by intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) or visual impairments, and cannot be attributed to a neurological condition that affects movement (e.g., cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, degenerative disorder). |

Diagnosis and treatment

According to the recommendations of the European Academy of Childhood Disability, the appropriate multidisciplinary team to diagnose DCD, examining the specific DSM-5 criteria for this disorder, should include a pediatric neurologist and an occupational therapist or physiotherapist trained in standardized motor assessment tools to evaluate children suspected of having this disorder (such as the MABC-2).

But in order to optimize attention to the impact of this disorder at other levels, with a broader multidisciplinary and task-oriented approach, it is advisable to incorporate other figures such as the neuropsychologist and the educational psychologist, without forgetting the fundamental role of the family, so that the educational, therapeutic and family. areas participate in a coordinated manner and in constant communication.

Thus, after an exhaustive and rigorous individualized assessment of the child, realistic objectives can be proposed that are in line with the needs of each setting.

In a comprehensive rehabilitative treatment approach for DCD we encounter the following disciplines:

Pediatric neurologist

Diagnosis and follow-up of the child with DCD. If there is comorbidity with attention deficit disorder (ADHD) consider the possibility of incorporating medication. Monitoring of progression and guidance to parents.

Neuropsychology

Emotional management, control and reduction of blockages and improvement of self-esteem. Also, seeking strategies to adapt to their differences and to face and overcome situations that cause them frustration.

At the cognitive level, the problems derived from DCD affect not only reading and writing and arithmetic, but also extend to attentional problems, executive functions (such as information processing speed, flexibility and planning) and visuospatial integration.

Likewise, other problems commonly associated with DCD are psychosocial difficulties, management of sedentarism and decreased participation in physical and social activities.

In a recent review on the influence of this disorder on physical, psychological and social functioning, the authors concluded that “children with DCD report lower self-efficacy and competence in the physical and social domains, experience greater symptoms of depression and anxiety, and show more externalizing behaviors (such as physical aggression, rule-breaking with cheating, stealing and property destruction) compared to typically developing children.”

Rehabilitative treatment of DCD

Below we show some exercises for the rehabilitative treatment of DCD from the NeuronUP platform to work from the neuropsychology area:

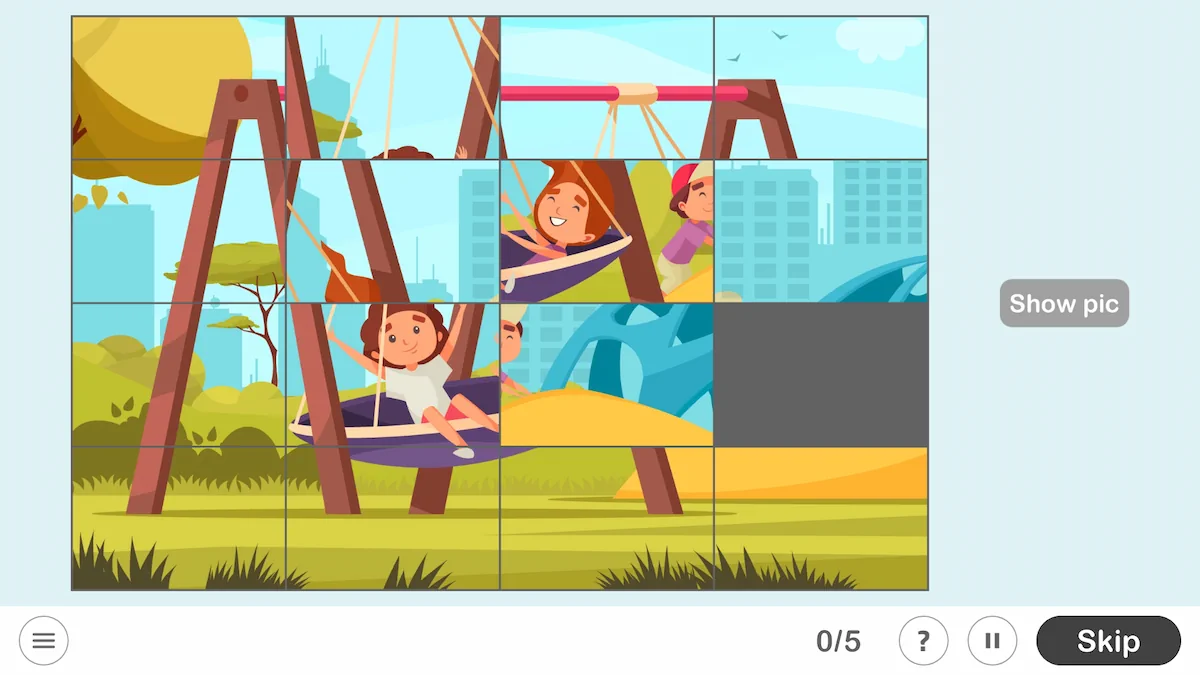

Visuospatial integration + planning

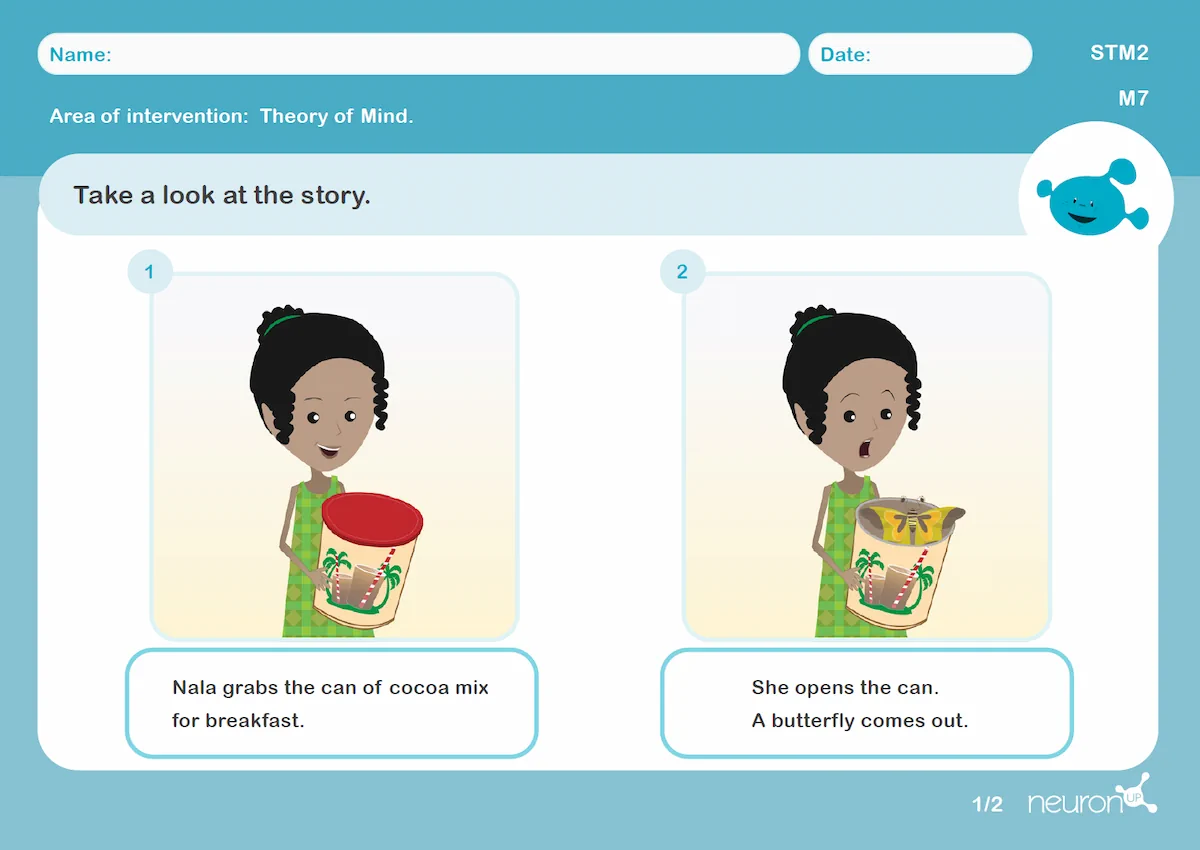

Language use and social cognition

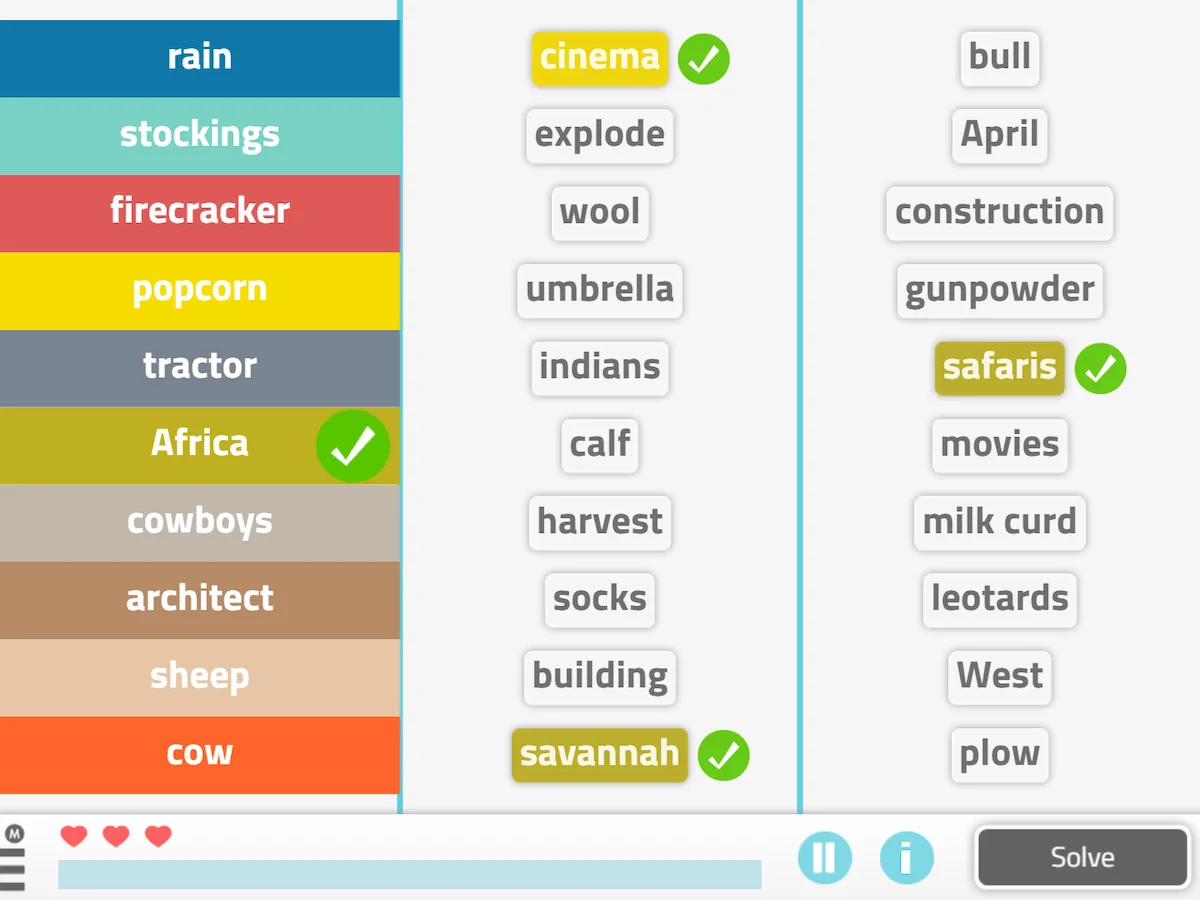

Reasoning and executive functions

Occupational therapy

Work is carried out aimed at improving motor skills, participation and autonomy in the activities of daily living. In addition, direct work with the child is sought, in constant coordination with the school and with the family to make the necessary adaptations.

It is also very important to work on learning step sequences to promote the automatization of routines for home and school.

Below we show some examples to work on and improve the performance of activities of daily living:

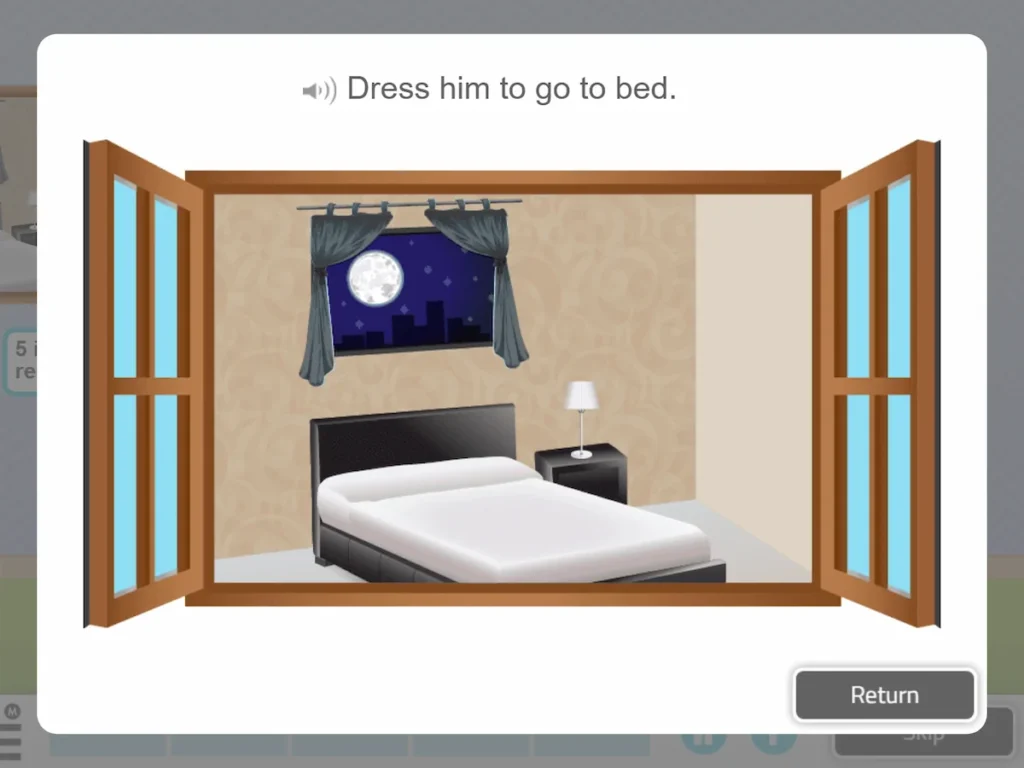

NeuronUP activity Get Dressed in which two fundamental aspects of children’s daily life are worked on: dressing and play.

These activities can also be worked on with paper and pencil, making a list of the things I need to put on when I am going to do sports.

Work at home, in a real context, when we get up one morning and have to put on our sports clothes because that day we have physical education.

In addition to work on activities of daily living, from occupational therapy and under the Sensory Integration approach, it is important to take into account the child’s sensory profile. The processing of sensory information (how the child processes stimuli coming from both his body and the outside) impacts his daily performance.

Physiotherapy

Coordination, gross motor skills, Physical Exercise, proprioception. As well as work focused on combating overweight or obesity, joint hypermobility, compromised physical condition and decreased participation in physical activities.

Educational psychology

Direct work in the educational field focused on school learning. Especially focused on enhancing reading and writing and mathematics.

Family

Throughout the whole process it is very important to be in coordination with the family. Since children spend most of the day between school and home. For this reason, it is in these two settings where professionals and families must help the child with strategies and by facilitating the environment and surroundings to enhance the improvement of their skills. Likewise, it is essential to involve them as much as possible in this process. Inform and train them, trying to make them understand what this disorder consists of and turning them into an active part of the rehabilitative work.

Similarly, new technologies such as virtual reality and stimulation platforms like NeuronUP open up a new path in the rehabilitation of neurodevelopmental disorders. Indeed, these allow us to motivate children and improve adherence to treatment, and with it, success and progress in their daily difficulties.

Finally, the NeuronUP platform allows us in a simple and categorized way to stimulate and enhance the different components that are the focus of work in developmental coordination disorder.

Authors

- Loinaz Guridi Antón (Occupational Therapist),

- Ramón Fernández de Bobadilla (Neuropsychologist),

- Neurobidea – Pamplona

Bibliography

- American Psychiatric Association (2014). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th Ed. Madrid: Editorial Médica Panamericana

- Crespo-Eguílaz, N. and Narbona, J. (2009) Procedural learning disorder: neuropsychological characteristics. Revista de Neurología 49 (8): 409-416

- Magallón, S. and Narbona J. (2009) Detection and specific studies in procedural learning disorder. Revista de Neurología 48 (Supl 2): S71-S76.

- Harris, S. R., Mickelson, E. C., &Zwicker, J. G. (2015). Diagnosis and management of developmentalcoordinationdisorder. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Associationjournal, 187(9), 659-65.

- Miyahara M, Hillier SL, Pridham L, Nakagawa S. Task-orientedinterventionsforchildrenwithdevelopmentalco-ordinationdisorder. Cochrane Database of SystematicReviews 2017, Issue 7. Art. No.: CD010914. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010914.pub2

If you enjoyed this article about developmental coordination disorder, you may also be interested in:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Tratamiento rehabilitador del trastorno del desarrollo de la coordinación

5 Activities Designed to Work with Children with ADHD

5 Activities Designed to Work with Children with ADHD

Leave a Reply