This article focuses on understanding how problems of impulsivity and decision-making originate and manifest in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Introduction

The Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that primarily affects the motor system. However, in recent decades, it has been recognized that the non-motor symptoms —particularly the cognitive and behavioral disorders— are equally relevant and can have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life.

One of the most complex and clinically problematic phenomena in this non-motor spectrum is impulsivity, understood as the tendency to respond quickly and disinhibitedly to stimuli without adequately considering the consequences. This alteration is closely linked to the decision-making process, which may be equally affected/compromised; this can lead to maladaptive behaviors, such as pathological gambling, hypersexuality, or compulsive shopping.

This article thoroughly analyzes the pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical manifestations and available therapeutic strategies to address impulsivity and decision-making difficulties in patients with Parkinson’s, with the aim of providing practical, up-to-date tools for health professionals involved in their assessment and treatment.

Impulsivity in Parkinson’s disease: what do we mean by it?

In the context of PD, impulsivity goes beyond mere restlessness or motor impulsivity. It manifests through impairment in behavioral self-control, characterized by:

- Lack of inhibition in the face of immediate rewards.

- Difficulty resisting impulses, desires or temptations.

- Repetitive or compulsive behaviors that compromise personal, social or financial well-being.

The medical literature groups these behaviors under the umbrella of impulse control disorders (ICDs), whose prevalence in PD is estimated between 13% and 40%, especially in patients treated with dopaminergic agonists. The most frequent ICDs include:

- Pathological gambling: difficulty controlling the urge to gamble, even when the consequences are negative.

- Compulsive buying: repeated and unnecessary acquisition of products, with accumulation and economic deterioration.

- Hypersexuality: abnormal increase in libido, with inappropriate or risky sexual behaviors.

- Punding: repetitive and purposeless motor activity, such as obsessively arranging objects or dismantling devices.

These behaviors have a great impact on the patient’s life, potentially leading to economic destabilization, family conflicts or social isolation… therefore early detection is key in clinical practice.

Neurobiological bases of impulsivity in Parkinson’s disease

From a neurobiological perspective, impulsivity in PD is related to a dysfunction of the dopaminergic system, especially in the mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways, which regulate motivation, reward and goal-directed behavior.

Under normal conditions, there is a balance between:

- The nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway ( substantia nigra – striatum): mainly affected in the motor symptoms of PD.

- The mesolimbic pathway (ventral tegmental area – nucleus accumbens), responsible for motivation and reward.

- The mesocortical pathway (tegmental area-prefrontal cortex): associated with cognition, particularly in the orbitofrontal and ventromedial regions, implicated in behavioral inhibition and ethical or social decision-making.

In PD patients, neuronal degeneration combined with dopaminergic treatment —especially non-ergot dopaminergic agonists such as pramipexole or ropinirole— can induce a hyperstimulation of the reward system, leading to increased vulnerability to ICDs.

This phenomenon is known as “dopaminergic sensitization” and explains why some patients develop compulsive behaviors suddenly when starting or increasing dopaminergic treatment.

Decision-making impairment in Parkinson’s disease

The decision-making process in Parkinson’s disease is compromised even from early stages of the disease. This impairment is expressed through:

- Choosing impulsive options with immediate rewards, to the detriment of long-term benefits.

- Difficulty learning from mistakes, which perpetuates unfavorable decisions.

- Reduced ability to evaluate risks and benefits, affecting the patient’s autonomy.

- Cognitive inflexibility, manifested as perseveration or mental rigidity in the face of changes in the environment or new rules.

This behavioral pattern falls within deficits in executive functions, which also include alterations in planning, abstract reasoning, working memory and response inhibition.

In clinical practice, these symptoms may go unnoticed if a specific neuropsychological assessment is not carried out. However, their impact on the patient’s daily life is profound, as it affects the ability to manage their treatment, organize routines, make financial decisions or maintain “quality” social relationships.

Clinical assessment of impulsivity and decision-making

Neuropsychological tools

Detection and quantification of impulsive symptoms in PD require validated tools adapted to this clinical profile. Among the most used are:

- QUIP-RS (Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease – Rating Scale): self-administered scale to identify the presence and severity of ICDs.

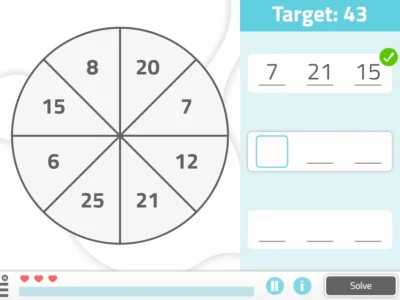

- Iowa Gambling Task (IGT): measures the ability to make decisions under uncertainty, simulating monetary gains and losses.

- Cambridge Gambling Task (CGT): evaluates decision-making under conditions of explicit risk.

- Hayling Test and Stroop Test: useful for measuring verbal inhibition and automatic responses and attentional control.

Qualitative clinical assessment

In addition to formal tests, it is essential to carry out a complete clinical assessment that includes:

- History of behavior before and after the start of dopaminergic treatment.

- Perception of the family environment regarding behavioral changes.

- Impact of impulsive behaviors on daily life.

The use of complementary scales such as the PDQ-39 (Parkinson’s disease quality of life questionnaire) or the Zarit (caregiver burden scale) allows contextualizing the impact of these symptoms on the patient and their environment.

Risk factors for impulsivity and decision-making impairment

Impulsivity and impaired decision-making in PD do not appear randomly. Several studies have identified predisposing factors, including:

- Treatment with dopaminergic agonists, especially at high doses or for long periods.

- Early onset of PD (<50 years), associated with greater lifetime exposure to dopaminergic drugs.

- Personal or family history of addictive disorders (gambling, alcohol, drugs).

- Preserved overall cognition, which paradoxically can facilitate impulsive behaviors without inhibitory control.

- Comorbid affective symptoms, such as depression, anxiety or bipolar disorder.

These elements should be considered during clinical follow-up to perform a proactive screening of patients at risk and prevent severe cognitive and behavioral complications.

Therapeutic approach

Pharmacological adjustment

The essential element of treatment for ICDs in Parkinson’s disease is the careful adjustment of dopaminergic medication, since there is a clear association between the use of dopaminergic agonists and the appearance of impulse control disorders. Multicenter studies such as Weintraub et al. (2010) have shown that up to 17% of patients treated with these drugs develop at least one ICD, compared with only 6% in those who do not use them.

Clinically recommended steps include:

- Gradual reduction of dopaminergic agonists, especially those with high affinity for D3 receptors, such as pramipexole and ropinirole. These molecules are strongly involved in modulating the reward circuit, which favors the emergence of compulsive behaviors (Voon et al., 2006).

- Individual evaluation of the risk-benefit balance, since reducing these drugs may imply a loss of motor control. An interdisciplinary approach is recommended, with active participation of the neurologist, the patient and their environment (Seppi et al., 2019).

- In some cases, replacement with levodopa may be necessary, which presents a lower risk of inducing ICDs, although its use should also be monitored, since it is not completely free of neuropsychiatric effects (Cilia et al., 2014).

This process should always be carried out in an individualized and gradual manner, since dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome (Dopamine Agonist Withdrawal Syndrome, DAWS) has been described, a clinical picture characterized by anxiety, dysphoria, insomnia, intense fatigue, depressive symptoms and even suicidal ideation, which can appear in up to 20% of patients after abrupt withdrawal of these drugs (Rabinak and Nirenberg, 2010).

Prevention of this syndrome requires gradual withdrawal under close medical supervision, with support from the mental health team when necessary.

Cognitive-behavioral intervention

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) adapted to the Parkinson’s context has proven effective in:

- Restructuring automatic thoughts that feed impulsive behaviors.

- Promoting impulse control through delay of gratification techniques.

- Developing coping strategies for risky situations.

Group work or family involvement can amplify the benefits, especially if integrated into a multidisciplinary approach.

Neuropsychological rehabilitation

Cognitive rehabilitation programs focused on executive functions (inhibition, planning, flexibility) can improve decision-making and reduce impulsivity.

Digital platforms such as NeuronUP, which offer structured activities with immediate feedback, allow implementing this type of training continuously, even at home.

New lines of research and future perspectives

The field of research on ICDs and decision-making impairment in Parkinson’s is rapidly expanding. Some promising approaches include:

- Functional neuroimaging (PET, fMRI) to study altered brain networks in real time.

- Deep brain stimulation (DBS): while useful for motor symptoms, it can worsen or improve ICDs depending on the brain target (subthalamic nucleus vs internal globus pallidus).

- Identification of genetic biomarkers: polymorphisms in dopaminergic genes such as DRD3 and COMT could explain individual susceptibilities.

- Predictive models with AI: machine learning algorithms to identify risk profiles and personalize treatments.

Conclusions

Impulsivity and impaired decision-making in Parkinson’s disease represent a multidimensional clinical challenge. Beyond the motor impact, these symptoms:

- Affect the patient’s quality of life and autonomy.

- Are often underdiagnosed and confused with psychiatric disorders.

- Require a systematic, interdisciplinary and personalized assessment.

The therapeutic approach should integrate pharmacological adjustment, cognitive intervention, family psychoeducation and the use of digital technologies for neurorehabilitation.

Bibliography

- Voon V, et al. (2011). “Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a cross-sectional study of 3090 patients.” Arch Neurol, 68(2), 241–246.

- Weintraub D, et al. (2010). “Impulsive and compulsive behaviors in Parkinson’s disease.” Current Opinion in Neurology, 23(4), 372–379.

- Cools R. (2006). “Dopaminergic modulation of cognitive function-implications for L-DOPA treatment in Parkinson’s disease.” Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 30(1), 1–23.

- Antonini A, et al. (2017). “Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: management, and future perspectives.” Mov Disord, 32(2), 174–188.

- Poletti M, Bonuccelli U. (2012). “Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: the role of personality and cognitive status.” J Neurol, 259(11), 2269–2277.

- Garcia-Ruiz PJ, et al. (2014). “Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: from bench to bedside.” Eur J Neurol, 21(6), 727–734.

- Dagher A, Robbins TW. (2009). “Personality, addiction, dopamine: insights from Parkinson’s disease.” Neuron, 61(4), 502–510.

- Weintraub D, Koester J, Potenza MN, et al. (2010). “Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: A cross-sectional study of 3090 patients.” Arch Neurol, 67(5), 589–595.

- Voon V, Hassan K, Zurowski M, et al. (2006). “Prevalence of repetitive and reward-seeking behaviors in Parkinson disease.” Neurology, 67(7), 1254–1257.

- Seppi K, Weintraub D, Coelho M, et al. (2019). “The Movement Disorder Society Evidence-Based Medicine Review Update: Treatments for the non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.” Mov Disord, 34(2), 180–198.

- Cilia R, Ko JH, Cho SS, et al. (2014). “Reduced dopamine transporter density in the ventral striatum of patients with Parkinson’s disease and impulse control disorders.” Brain, 137(Pt 11), 3109–3119.

- Rabinak CA, Nirenberg MJ. (2010). “Dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome in Parkinson disease.” Arch Neurol, 67(1), 58–63.

If you enjoyed this blog post about impulsivity and decision-making impairment in Parkinson’s disease, you will likely be interested in these NeuronUP articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Impulsividad y deterioro de la toma de decisiones en la enfermedad de Parkinson: un desafío clínico creciente

Sustained Attention Game for Children: Colored Balloons

Sustained Attention Game for Children: Colored Balloons

Leave a Reply