Deimer Andrés Acuña Fuentes, a clinical neuropsychologist with experience in clinical work with older adults, explores in this article the differences between mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia from a clinical neuropsychology perspective.

Introduction

In today’s context of accelerated population aging, neurocognitive disorders have become one of the main challenges for public health systems worldwide (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021).

It is estimated that by 2050, more than 2 billion people will be over the age of 60 (United Nations, 2020), a demographic reality that has highlighted the urgent need to accurately distinguish between the trajectories of normal cognitive aging, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia.

This differentiation has not only clinical and diagnostic implications, but also guides therapeutic decisions, prognoses, and intervention policies in mental health and neurogeriatrics. Both MCI and dementia are clinical expressions of neurocognitive impairment, but they differ significantly in terms of intensity, clinical course, functional impact, and potential reversibility.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is defined as a syndrome characterized by an objective cognitive decline greater than expected for an individual’s age and educational level, which does not significantly interfere with functional independence. Although it represents a risk condition for progression to dementia, not all cases evolve into it.

By contrast, dementia—whether degenerative, vascular, or of another etiology—implies a severe and persistent deterioration across multiple cognitive domains accompanied by a clear impairment in basic and instrumental activities of daily living, which affects the individual’s overall functioning in an irreversible manner in most cases.

The clinical problem is that the boundaries between these two conditions are often blurred, especially in the early stages. The progression from MCI to dementia does not follow a uniform pattern, as multiple other trajectories are possible, such as stabilization or even symptom reversal, which further complicates clinical prediction. Added to this is the presence of affective comorbidities such as depression and anxiety, which can mimic or worsen cognitive symptoms, creating an ambiguous clinical picture that demands refined diagnostic tools and a comprehensive perspective.

From clinical neuropsychology, this scenario highlights the need for precise diagnostic decisions that enable early, reliable, and functionally meaningful identification of neurocognitive disorders. Through the systematic assessment of domains such as episodic memory, sustained attention, processing speed, executive functions, and language, professionals can distinguish between normal aging, MCI, and early dementia.

This differentiation becomes even more valuable when integrated with information from structural and functional neuroimaging, as well as biochemical biomarkers such as beta-amyloid peptide, TAU protein, or neurofilament levels, which enhance diagnostic accuracy.

At a therapeutic level, clearly identifying the stage a patient is in makes it possible to design interventions tailored to their needs. While in MCI the focus is on prevention, cognitive stimulation, and modification of risk factors, in dementia a functional approach is needed, centered on residual autonomy and quality of life. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation that combines clinical judgment with neuropsychological and biomedical evidence becomes the cornerstone for mapping effective care pathways.

This article aims to provide a critical and up-to-date review of the key differences between MCI and dementia from a neuropsychological perspective, addressing defining features, diagnostic tools, risk factors, biomarkers, and psychiatric comorbidities. In addition, it will discuss the relevance of adopting a rigorous and multidimensional clinical approach that helps refine diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making in a field where boundaries can be blurry, but decisions must be accurate.

What is mild cognitive impairment (MCI)?

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a clinical syndrome manifested as an objective decline in one or more cognitive domains such as memory, attention, language, or executive functions, exceeding what would be expected in normal aging, without clearly compromising the individual’s overall autonomy.

Although basic activities of daily living are usually preserved, subtle difficulties may emerge in more complex instrumental tasks such as financial management, activity organization, or keeping appointments, reflecting an early vulnerability in functioning.

These manifestations, often underestimated, may constitute the earliest signs of an ongoing neurodegenerative process. Early identification of MCI is crucial for establishing baselines, designing targeted interventions, and potentially modifying the clinical course toward more advanced stages such as dementia.

Clinical characteristics of MCI

- Subjective complaints of memory and/or other cognitive functions (such as attention, language, executive functions).

- Objective impairment in one or more cognitive domains documented by neuropsychological tests.

- Preservation of functional independence, although there may be difficulty in complex tasks (money management, travel planning, use of new technologies).

- Awareness of the deficit is usually preserved.

Clinical subtypes of MCI

- Single-domain amnestic: exclusive impairment of memory. Considered the subtype with the highest risk of progression to Alzheimer’s disease.

- Multi-domain amnestic: impairment of memory and at least one other cognitive domain.

- Single-domain non-amnestic: impairment of a non-memory domain, such as attention or executive functions.

- Multi-domain non-amnestic: impairment of two or more non-memory domains.

Risk factors associated with MCI

- Advanced age (from 60 years onward).

- Low educational level and premorbid cognitive reserve.

- Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

- Family history of dementia.

- Presence of the APOE-ε4 allele.

- Sedentary lifestyle and social isolation.

- Mood disorders (depression and anxiety).

Course of MCI

Longitudinal studies show that between 10–15% of patients with MCI progress to dementia each year. However, it is estimated that 20–30% may remain stable or even improve, especially if early interventions are implemented and modifiable factors are controlled. These findings reinforce the importance of early diagnosis and a preventive approach.

What is dementia?

Dementia, unlike MCI, represents a more advanced stage of cognitive decline, characterized by the presence of deficits in at least two cognitive domains that significantly interfere with the individual’s functioning. This deterioration affects not only memory, but also language, judgment, abstract reasoning, executive functions, and visuospatial abilities. Disease progression may vary depending on etiology, with Alzheimer’s disease being the most common (American Psychiatric Association, 2014).

Clinical characteristics of dementia

- Impairment of multiple cognitive domains: memory, language, executive functions, attention, gnosias, and praxis.

- Progressive functional decline.

- Changes in personality and behavior.

- Reduced awareness of the cognitive deficit.

- Changes in mood and behavior; presence of symptoms such as anxiety and depression; mood swings and personality changes; among others.

Risk factors for dementia

- Age (>65 years).

- Genetics (mutations in APP, PSEN1, PSEN2 genes; presence of the APOE-ε4 allele).

- Poorly controlled chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia).

- Acquired brain injury.

- Low educational level.

- Chronic exposure to toxins or alcohol.

- Social isolation and low cognitive stimulation.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Early signs, symptoms, and disease progression: mild cognitive impairment (MCI) vs. dementia

1. Early signs of MCI and dementia

Early signs of mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

In MCI, early signs are subtle and may go unnoticed by patients or their family members in the initial stages. Individuals may notice mild difficulties in cognitive performance, especially in areas such as memory, attention, and executive functions, but without significantly interfering with their daily activities.

Early signs include:

- Mild short-term memory difficulties: patients may forget recent details, such as where they left an object, or need to make extra effort to remember names or recent events.

- Difficulty concentrating or maintaining attention: people with MCI may experience problems sustaining attention on prolonged tasks, which can lead to distraction and slower task completion.

- A tendency to lose track of conversations: difficulty keeping up with the pace of a conversation or recalling details of a recent discussion can be an early sign of cognitive decline.

- Problems with organization and planning: people with MCI may notice it is harder to organize daily activities or make plans effectively, which can affect the completion of complex tasks.

- Low performance on neuropsychological tests: in early stages, performance on specific memory and executive function tests may be suboptimal, though not severe enough to warrant a dementia diagnosis.

Early signs of dementia

In dementia, early signs are more pronounced and tend to significantly affect the person’s daily activities. Cognitive impairment is more severe and persistent.

Early signs include:

- Significant memory loss: one of the earliest and most evident symptoms of dementia is long-term memory loss, especially the inability to recall past events—even important ones—and difficulty learning new information.

- Spatial and temporal disorientation: people with dementia may get lost easily, even in familiar places, and show confusion about the date, time, or location.

- Difficulty carrying out everyday tasks: an increasing inability to perform daily activities such as getting dressed, cooking, or managing finances is observed. People with dementia may need help with tasks they previously carried out independently.

- Language impairments: vocabulary loss, difficulty forming coherent sentences, and an inability to follow or initiate conversations are common in early stages of dementia.

- Impaired judgment and decision-making: patients with dementia may have difficulty making decisions, which can put their safety and the safety of others at risk.

2. Symptoms of MCI and dementia

Symptoms of mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

MCI symptoms are more subtle, which makes early detection difficult without a thorough neuropsychological assessment.

Key symptoms include:

- Memory: people with MCI often experience forgetfulness of recent events but do not show a global memory loss. They often remember older information, while recent memories are more affected.

- Executive functions: the ability to plan, organize, and make decisions may be affected. People with MCI may have difficulty handling multiple tasks at once or completing complex tasks that require managing multiple details.

- Language: although language problems are not as prominent, they may have word-finding difficulties, which can lead to frequent pauses during conversations.

- Attention and concentration: the ability to sustain attention for extended periods or perform tasks requiring concentration is affected, especially in noisy environments or with multiple stimuli.

- Emotional behavior: although people with MCI do not usually have severe psychiatric disorders, they may experience anxiety, sadness, or frustration due to the cognitive difficulties they face. However, affective disorders are not a diagnostic criterion for MCI, although comorbidity with anxiety or depression is common.

Symptoms of dementia

In more advanced stages of dementia, symptoms are much more severe and affect the person’s daily functioning.

Common symptoms include:

- Severe memory loss: in advanced dementia, patients not only forget recent events, but also essential details of their lives, such as the names of close family members or friends.

- Disorientation: patients may become confused about the date, time, place, or even the identity of people around them. They may get lost in their neighborhood or in familiar places.

- Inability to perform everyday activities: in more advanced stages, people with dementia cannot perform daily activities such as dressing, eating, or bathing without help.

- Language disorders: the ability to communicate decreases considerably. Patients may lose the ability to speak coherently, and in advanced stages may not be able to speak at all.

- Changes in personality and behavior: patients may show significant personality changes, such as becoming more irritable, anxious, or apathetic. They may also exhibit repetitive behaviors, such as wandering, or have episodes of aggression or agitation.

- Impulsive or inappropriate behaviors: loss of judgment and inability to understand social norms can lead to inappropriate or dangerous behaviors.

3. Progression of MCI and dementia

Progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

The course of MCI is heterogeneous and depends on multiple individual and clinical factors. In a considerable proportion of cases, cognitive changes remain stable for years without progressing to a major neurocognitive disorder. However, in other patients—especially those with amnestic MCI—there is a higher likelihood of conversion to Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias. The annual conversion rate from MCI to dementia is estimated to range from 10% to 20%, with faster progression in the presence of risk factors such as arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, family history of dementia, and low cognitive reserve.

In certain situations, MCI may be reversible, especially when potentially modifiable underlying causes are identified and treated, such as vitamin deficiencies (e.g., B12), thyroid dysfunction, or mood disorders. However, in the absence of adequate therapeutic interventions, decline tends to progress, underscoring the importance of early detection and a comprehensive clinical approach.

Progression of dementia

Dementia is a chronic and progressive neurodegenerative condition, characterized by significant and widespread deterioration across multiple cognitive domains. In early phases, patients may retain some functional ability in daily activities; however, as the disease progresses, the loss of cognitive and adaptive capacities intensifies, profoundly affecting memory, judgment, language, orientation, and behavior.

In Alzheimer’s disease, progression is typically insidious but steady, with a clinical course that can extend over years. In advanced stages, patients require continuous supervision and complex supportive care. Other forms of dementia, such as frontotemporal dementia or dementia associated with Lewy bodies, show different clinical trajectories, with distinctive early symptoms such as marked behavioral changes or early motor impairment.

Given that MCI and dementia share early symptoms in domains such as episodic memory, sustained attention, or executive functions, it is essential to differentiate between the two clinical pictures. Whereas MCI involves limited cognitive decline and a relative preservation of functional independence, dementia entails a more severe and progressive loss of personal independence. A specialized neuropsychological assessment—sensitive to contextual and clinical factors—is fundamental to establishing an accurate diagnosis, guiding prognosis, and designing personalized therapeutic strategies that help preserve quality of life.

Differential diagnosis: mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia?

From clinical neuropsychology, the differential diagnosis between mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia involves not only identifying objective deficits in cognitive domains, but also understanding functional depth, clinical course, the qualitative profile of errors, and the emotional impact of the changes.

Below is a structured comparative table that summarizes the fundamental differences between both clinical entities, useful both for diagnostic practice and for prognostic and intervention guidance:

| Clinical characteristic | MCI | Dementia |

| Functional impact | General preservation of instrumental and basic activities; possible mild difficulty. | Clear functional impairment; interferes with independence in daily activities. |

| Memory domain | Subjective complaints and objective recall failures; improves with cues or repetition. | Significant forgetfulness, loss of encoded information, poor response to external aids. |

| Other cognitive domains | Generally, one domain is most affected (e.g., attention, executive functions). | Global impairment: memory, language, gnosias, praxis, executive functions, visuospatial. |

| Awareness of the deficit | Preserved: the patient recognizes and is distressed by their difficulties. | Frequently impaired: partial or complete anosognosia. |

| Affective-emotional state of the condition | Prevalence of anxiety, reactive depressive symptoms, fear of progression. | Depressive or anxious symptoms may coexist, though not always reactive; greater emotional lability. |

| Neuropsychiatric symptoms of the condition | Generally absent or very mild. | Apathy, disinhibition, irritability, prominent and aggressive neuropsychiatric symptoms. |

| Clinical course | Slow; may remain stable or improve with intervention; risk of conversion to dementia. | Progressive, irreversible in most etiologies; continuous decline. |

| Adaptive capacity | Effective use of compensatory strategies and routines. | Significant decrease in adaptive flexibility; progressive disorganization. |

| Language | Verbal fluency and naming generally preserved. | Anomia, paraphasias, difficulties in comprehension and narrative discourse. |

| Attention and processing speed | Mild slowing; sustained attention is preserved. | Attentional difficulties, difficulty with simultaneous tasks; marked cognitive slowing. |

| Executive functions | Mild difficulties in planning or multitasking. | Severe disorganization, loss of initiative, poor judgment and abstraction. |

| Orientation | Full personal, spatial, and temporal orientation. | In advanced stages, orientation is lost in all three spheres. |

In clinical practice, this differentiation is critical for timely intervention, designing individualized therapeutic strategies, and providing psychoeducational support to families. While MCI represents a risk condition and a possible window for neuroprotective intervention, dementia indicates a substantial and irreversible loss of functional brain networks, with global consequences for the individual’s autonomy. Therefore, an in-depth, contextualized, and longitudinal neuropsychological assessment remains the diagnostic cornerstone in this field.

Neuropsychological assessment: key to the differential diagnosis between MCI and dementia

Neuropsychological assessment is the gold standard in the clinical approach to cognitive impairment, as it makes it possible to accurately identify impaired, preserved, and at-risk cognitive profiles within the same person (Muñoz-Céspedes, Tirapu-Ustárroz, & Ríos-Lago, 2013).

This differentiation is essential for characterizing the clinical course and establishing an appropriate differential diagnosis. The relevance of this assessment is not limited to quantitative scores obtained from standardized tests; it also includes a qualitative analysis of error patterns, strategies used, learning capacity, long-term information consolidation, and the degree of adaptive functioning.

The main objective of this assessment is to build a detailed neurocognitive profile that makes it possible to distinguish between mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and the different forms of dementia. This differentiation is especially critical in the early stages of the clinical picture, where manifestations may be subtle and overlapping.

Additionally, in the clinical interview as part of the assessment, lab tests or other measures make it possible to identify potentially reversible conditions such as acute confusional syndromes (delirium), metabolic disturbances, nutritional deficiencies (for example, vitamin B12 or folate deficiency), medication side effects, and mood disorders or sleep apnea, which can mimic neurodegenerative decline without being one. Identifying these conditions is key to preventing misdiagnosis and intervening early.

The assessment protocol should be broad and flexible, allowing the test battery to be adapted to the patient’s characteristics (age, educational level, medical history, functional status).

Structured approach in clinical practice

In clinical practice, a structured approach includes, for example:

1. Interview and clinical observation

- Structured general interview: collection of medical, psychiatric, functional, family, and social history.

- Neuropsychological clinical history: identification of current cognitive complaints, their course over time, and their functional impact.

- Cognitive-behavioral clinical observation: qualitative recording of behavior, deficit awareness, perseverations, test-taking attitude, and level of cooperation.

2. General cognitive assessment

- Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE): a brief screening test that explores orientation, attention, calculation, immediate and recent memory, language, and visuospatial skills. It is useful for detecting moderate to severe impairment, although it has lower sensitivity in early stages.

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): a screening instrument more sensitive to MCI. It assesses domains such as memory, language, orientation, attention, executive functions, and visuospatial skills. It is considered superior to the MMSE in patients with higher education or subjective cognitive complaints.

- NEUROPSI Attention and Memory – Second Edition: a Latin American battery widely validated for Spanish-speaking populations. It analyzes sustained and selective attention, verbal and visual memory, encoding, free recall and cued recall, recognition, and learning curve.

Key subtests of the NEUROPSI-NAM (Attention and Memory – Second Edition) allow an exhaustive assessment of various cognitive functions.

These include:

- Digits forward and backward, which assesses attention and auditory memory.

- Blocks, which measures visuospatial skills and perceptual organization.

- Visual detection and Serial sequences, which explore selective and sustained attention.

- Verbal memory curve, which assesses the ability to consolidate and retrieve information.

- Paired associates, which measures associative memory and verbal learning ability.

- Logical memory, which assesses verbal memory using narrative material.

- Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure (copy and recall), which measures visuoconstructive skills and visual memory.

- Spontaneous verbal memory, with cues and recognition, which explores verbal memory in retrieval and recognition.

- Face memory (encoding and recall), which assesses the ability to recognize and remember faces.

- Category formation, which measures categorization skills and thought organization.

- Verbal fluency tasks: assesses productivity, strategy, perseverations, and cognitive flexibility (in phonological, semantic, and nonverbal tasks).

- Motor functions, which explore motor planning and execution.

- The Stroop Test, which assesses inhibitory control and executive functions.

Each of these subtests provides a comprehensive view of the cognitive processes involved in attention, memory, executive functions, and motor capacity. Likewise, some additional tests help assess language and frontal functions.

One example is the Boston Naming Test (short or extended version), a test used to evaluate object-naming ability. The patient must name a series of pictures that range from more common to more complex. Difficulty increases as the items progress. It is useful for detecting anomic aphasia and aphasia in general.

Another example is the Tower of London, which measures executive functions such as planning, cognitive flexibility, and problem solving.

3. Functional assessment

- Barthel Index: evaluates the level of independence in basic activities of daily living (BADLs) such as eating, hygiene, and dressing, among others.

- Lawton and Brody Scale: determines functioning in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) such as managing finances, using the phone, and transportation, among others. It is highly sensitive in early stages of decline.

4. Affective and behavioral assessment

- Beck Depression Inventory – BDI-II and PHQ-9: screening for depressive symptoms, common in the context of cognitive impairment.

- Neuropsychiatric Inventory – NPI-Q: assesses behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with neurodegenerative diseases (apathy, hallucinations, agitation, etc.).

- Memory Complaint Questionnaire (MAC-Q): measures the patient’s and/or caregivers’ subjective perception of decline.

5. Global severity scales and clinical diagnosis

- Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): scale that rates memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care. It provides a global score (0 to 3) for clinical staging of dementia.

- Global Deterioration Scale (GDS): classifies impairment into seven stages, from normal functioning to severe dementia. Especially useful for follow-up in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Blessed Dementia Scale: measures the degree of functional and behavioral deterioration. It is based on caregiver information to detect progression of disability.

6. Possible additional tests

- Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) or Wechsler Memory Scale-III (WMS-III): for a detailed assessment of verbal memory, encoding, and recall.

- Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST): assesses cognitive flexibility and abstract thinking.

- Trail Making Test A and B (TMT-A/B): explores sustained attention, processing speed, and mental set-shifting.

- Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure: test that evaluates visuoconstructive skills, visual memory, and perceptual organization. Clinical use: sensitive to frontal and parietal damage, executive impairment, dementias, and acquired brain injury.

- De Renzi Test: assessment of language functions and apraxia, including verbal comprehension, naming, and repetition. It is useful for identifying language disorders and ideational and ideomotor apraxia.

- Webster Scale (Webster DD): used in patients with Parkinson’s disease and neurodegenerative disorders. It measures disability in fine motor movements and is essential for assessing ideational and motor apraxia, especially in object-manipulation tasks.

Comprehensive assessment and contextualized diagnosis

Comprehensive assessment and contextualized diagnosis involves integrating quantitative results obtained from neuropsychological tests with qualitative observation of the patient’s behavior.

This approach makes it possible to differentiate typical cognitive profiles, such as amnestic MCI versus multi-domain MCI, as well as to identify dementia according to each of its etiologies: neurodegenerative, vascular, or mixed, as well as infectious dementias, metabolic dementias, tumor-related dementias, or dementias due to traumatic brain injury.

Information gathered from key informants, such as family members or primary caregivers, together with functional and clinical analysis, provides an in-depth understanding of the patient’s cognitive and adaptive status, enabling an accurate, personalized diagnosis with predictive value.

Treatments and strategies for cognitive stimulation

Approaches to MCI and dementia must be individualized, multimodal, and interdisciplinary. Below are differential strategies for each condition:

1. Treatments and cognitive stimulation strategies in mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

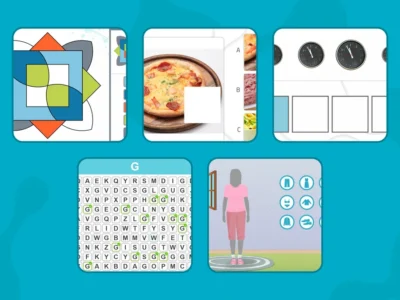

- Targeted cognitive stimulation: structured exercises aimed at memory, attention, language, and executive functions. They are delivered in manual or computerized formats and seek to preserve cognitive performance by activating neural networks that are still functional.

- Regular physical exercise: moderate aerobic activity (walking, swimming, yoga) improves brain oxygenation, stimulates neurogenesis, and regulates mood. It is adapted to the patient’s physical condition to ensure benefits without risks.

- Management of modifiable risk factors: includes controlling hypertension, diabetes, sleep apnea, dyslipidemia, smoking, and emotional health. Managing these factors significantly reduces progression to dementia.

- Mindfulness and metacognitive training: promote present-moment attention, awareness of cognitive functioning, and self-regulation. They help the patient identify errors and apply compensatory strategies with less emotional impact.

- Music therapy: the therapeutic use of music to stimulate autobiographical memory, reduce anxiety, and encourage emotional expression. It can be active (singing/playing) or receptive (listening), depending on preferences and abilities.

- Group cognitive stimulation therapies: group-based interventions combining cognitive exercises with social interaction. They reinforce cognitive skills, reduce isolation, and improve mood and patient motivation.

- Meaningful occupational activities: participation in satisfying tasks (reading, cooking, gardening). They support self-esteem, cognitive functioning, and preservation of social roles, with occupational therapy support if needed.

- Emotional support and brief psychotherapy: psychological care to address anxiety, depression, or frustration associated with decline. Cognitive behavioral therapy or acceptance-based approaches are recommended, adapted to the patient’s needs.

- Neuroprotective nutrition: promoting a balanced diet rich in omega-3s, antioxidants, and vitamins (such as the Mediterranean diet), which has shown positive effects on preventing cognitive decline and brain inflammation.

2. Treatments and cognitive stimulation strategies in dementia

- Structured cognitive stimulation: cognitive stimulation is a core pillar of non-pharmacological dementia treatment. It focuses on strengthening and preserving residual cognitive functions such as attention, memory, language, executive functions, praxis, and gnosias. It is delivered through structured activities (individual or group) such as semantic and episodic memory exercises, problem solving, concept association, reading, mental games, time and place orientation, among others. This intervention not only improves functioning and cognitive performance, but also promotes self-esteem, reduces social isolation, and slows the degenerative course.

- Adapted physical activity: regular physical exercise has a notable impact on maintaining mental and cognitive health by stimulating neurogenesis, increasing cerebral blood flow, and reducing the risk of progressive decline. It must be adapted to the individual’s physical limitations and restrictions, ensuring a safe, progressive, and beneficial approach. Examples include assisted walks, low-impact exercises, tai chi, gentle gymnastics, and functional physiotherapy. In addition to neurological benefits, exercise also contributes to emotional well-being, agitation management, and improved sleep and quality of life.

- Group psycho-stimulation therapies: group interventions provide social, emotional, and cognitive benefits. Through structured sessions, they promote: (Maintaining conversational language. Interpersonal validation. A sense of belonging and participation.) They may include orientation activities, cognitive games, gentle motor exercises, themed discussions, and artistic or creative expression. They are particularly effective in counteracting isolation, apathy, and functional decline.

- Music therapy: music therapy uses musical elements (rhythm, melody, harmony, improvisation, and listening) to stimulate cognitive, sensory, and emotional functions. In people with dementia, music can: Reactivate autobiographical memories. Reduce agitation and anxiety. Improve social interaction. Strengthen mood. The intervention may be passive (guided listening) or active (singing, movement, using instruments), and should be guided by a trained music therapist.

- Reminiscence and validation therapies: reminiscence therapies use meaningful autobiographical memories to strengthen identity, foster emotional connection, and reaffirm a sense of self. Resources such as photographs, music, meaningful objects, and oral storytelling are used. Emotional validation, in turn, is a technique focused on accepting and understanding the patient’s emotional reality, even when it differs from objective reality, reducing distress, rejection, and relational conflicts.

- Multisensory stimulation (Snoezelen room): this therapeutic approach is based on controlled sensory stimulation (vision, hearing, smell, touch, proprioception) through environments designed with soft lights, relaxing sounds, aromas, textures, and vibrations. It is especially useful in moderate or severe phases, where verbal communication is limited. It improves mood, reduces agitation, promotes relaxation, and strengthens connection with the environment.

- Adapted functional training: seeks to preserve patient independence in basic and instrumental activities of daily living, such as personal hygiene, dressing, eating, money management, phone use, or meal preparation. This training should be personalized, considering the level of impairment and remaining abilities. It relies on techniques such as modeling, chaining, step-by-step instruction, and the use of visual or technological aids.

- Emotional and behavioral intervention: people with dementia often present behavioral and psychological symptoms such as apathy, depression, anxiety, agitation, or aggressiveness. Intervention includes: applying behavioral techniques to reduce disruptive behaviors (positive reinforcement, token economy, ignoring inappropriate behaviors); family psychoeducation and behavior-management training; emotional validation therapies and individual or group psychological support. These strategies improve the patient’s quality of life and reduce caregiver burden (García Alberca, 2019).

- Specific pharmacotherapy: in certain types of dementia, especially Alzheimer’s disease, pharmacotherapy may be indicated with: cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine), useful in mild to moderate stages; memantine (NMDA antagonist), used mainly in moderate to severe stages. These medications must be prescribed and monitored by a specialist physician, and always as part of a multimodal approach, not as the only measure, since benefits remain limited and do not modify the progressive course of the disease (Cummings, Morstorf, & Zhong, 2014).

In addition to these treatments and strategies for cognitive stimulation—both for MCI and for dementia—it is important to highlight that psychoeducation for the patient and their family is essential to promote understanding of the clinical picture and its potential progression. Psychoeducation provides tools for teaching compensatory strategies such as planners, routines, environmental cues, and mnemonic techniques that not only improve autonomy but also reduce the emotional impact of decline, thereby strengthening family support.

Conclusion

Distinguishing between mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia is one of the most relevant challenges—and often underestimated— in contemporary clinical neuropsychological practice. It is not merely a nosological categorization, but a diagnostic decision with profound implications for prognosis, access to specific interventions, care planning, and the preservation of patient autonomy.

From the perspective of clinical neuropsychology, establishing this differentiation requires a comprehensive, sensitive, and culturally informed assessment that goes beyond quantitative performance on cognitive tests. It is necessary to consider the qualitative pattern of errors, the learning curve, progressive functional decline, and indicators of integrity in specific neurofunctional networks.

Patients with MCI, despite presenting evident deficits, maintain a relative functional independence and active compensatory abilities. By contrast, in dementias, neurocognitive and behavioral disruption is more severe, extensive, and progressive, significantly impacting daily life. Recognizing these differences early is essential to establishing a timely intervention framework aimed both at slowing decline and preserving quality of life.

Clinical neuropsychology, as a bridge discipline between neurology, psychiatry, and psychology, plays an irreplaceable role in this process. Not only in diagnostic assessment, but also in designing cognitive rehabilitation programs, guiding families, and training professionals who care for aging populations.

In the context of global population aging and the rise of neurodegenerative diseases, the approach to cognitive impairment must necessarily be interdisciplinary, grounded in scientific evidence, ethics, and a human-centered model of clinical care. Only through this integration will it be possible to preserve the patient’s identity, even in the face of progressive memory decline, and ensure dignified, personalized care filled with hope that promotes the individual’s overall well-being.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2014). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Cummings, J., Morstorf, T., & Zhong, K. (2014). Alzheimer’s disease drug-development pipeline: Few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 6(4), 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/alzrt269

- García-Alberca, J. M. (2019). Stress and coping in caregivers of people with dementia. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 54(2), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2018.07.003

- Muñoz-Céspedes, J. M., Tirapu-Ustárroz, J., & Ríos-Lago, M. (2013). Neuropsychological assessment: A review of procedures, instruments, and their clinical usefulness. Revista de Neurología, 57(Suppl 1), S113–S122.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2018). Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. NICE Guideline [NG97]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97

- World Health Organization. (2021). Global report on Alzheimer’s disease. https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- Peña-Casanova, J., & Alegret, M. (2020). Non-pharmacological intervention in people with dementia. Neurología, 35(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2018.07.002

- Petersen, R. C., Lopez, O., Armstrong, M. J., Getchius, T. S., Ganguli, M., Gloss, D., Gronseth, G. S., Marson, D., Pringsheim, T., Day, G. S., & Sager, M. (2018). Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 90(3), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000004826

- Spector, A., Orrell, M., Davies, S., & Woods, B. (2001). Reality orientation for dementia: A systematic review of the evidence of effectiveness from randomized controlled trials. The Gerontologist, 40(2), 206–212. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/40.2.206

- Yanguas, J. (2006). Psychosocial interventions with people with dementia: Toward person-centered care. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 41(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0211-139X(06)74465 – 3

If you enjoyed this article on clinical differences, diagnosis, and cognitive stimulation in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia, you’ll likely be interested in these NeuronUP articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Deterioro cognitivo leve o demencia: diferencias clínicas, diagnóstico y estimulación cognitiva

The assessment of decision-making in neuropsychology

The assessment of decision-making in neuropsychology

Leave a Reply