Clinical neuropsychologist Aarón F. Del Olmo explains in this article what cognitive reserve is, how it works and its relationship with brain injury.

Some say that if the last century was the century of genetics, this century in which we live is the century of the brain. And it is true that as the years of these early decades go by we are beginning to understand a little how the brain works and how it relates to the environment to help us adapt to it. Studies of people who have suffered a brain injury have contributed a lot, but as often happens the more we learn, the more questions arise: How is it possible that some people evolve so differently in their recovery from similar injuries? Why do similar lesions sometimes not imply the same type of clinical alteration? And one of the paradigms that attempts to address the answers is that of cognitive reserve.

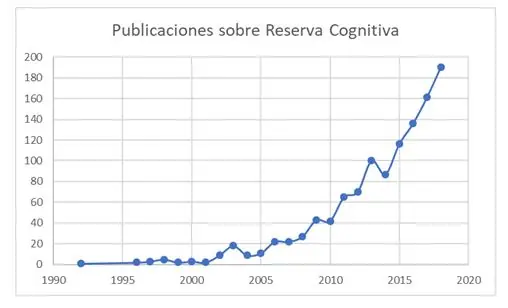

This is not a recent paradigm, but it is a term that in recent years has begun to find a place in our conversations about neuropsychology and brain injury. An example of this is the increase in publications on this topic in their title (Source: PubMed) which has gone from 183 in the first decade of the 21st century to 967 in the current decade that has not yet concluded (the evolution can be seen in the following graph).

Is brain reserve the same as cognitive reserve?

However, the problem with this term is really understanding its meaning and what it can or cannot contribute to our daily work. For this it is interesting to differentiate between brain reserve and cognitive reserve, terms that are mistakenly used interchangeably even though they imply different assumptions. On the one hand, the term brain reserve derives from post-mortem studies that Katzman and colleagues (1) carried out in a sample of healthy older people and with Alzheimer’s disease, finding that there was a lack of a direct relationship between amyloid burden and the cognitive signs shown. The explanation they found was that the brains of the people who had endured more damage, without showing it in life, were larger. This was directly linked to genetic issues, intelligence in general (tied to hereditary factors) and formal education which affects neurodevelopment by generating greater synaptic density (2). However, this model remains somewhat static (there is the same threshold for everyone from which we show damage) and with a certain limitation of action at the intervention level. In a way, it also reflected older conceptions of brain functioning (more structural).

This term was considered relevant and led to the use of coarse measures of brain size, such as the skull circumference itself. However, this idea fell relatively short, especially as knowledge about how the brain works advanced, thanks in part to functional neuroimaging techniques. In fact, based on brain functioning, Stern (3) developed a more dynamic hypothesis, and starting from the basis that there really are more efficient brains or with greater compensatory capacity, without the need to tie that to their size. That is, there are people who can maintain better cognitive functioning in the face of damage than others and, therefore, that threshold of the capacity to withstand damage would vary greatly from one person to another. The most interesting part of this hypothesis is that it proposed the capacity to modify that reserve (acquire it or lose it) depending on lifestyle, pointing to cognitively stimulating activities, physical activity or the social component as ways to do so.

Although they are two different models (although the terminology is sometimes used loosely) the truth is that one could argue that both interact. Each of us has a genetic endowment, but at the same time what is done with it is what will help to have more or less cognitive reserve.

How does this reserve work?

The word reserve refers to “accumulating” something, so in theory the term cognitive reserve could be understood as “accumulating cognition”; after all, the idea underlying this reserve is precisely to have an extra of “cognition” to remain functional when a brain injury occurs (or accumulates progressively). The main basis of this accumulation comes from the term neuroplasticity, that is, the capacity of the brain to react to the environment and be modified by exposure to it. But as mentioned before, both for better and for worse.

Undoubtedly the idea of positive and negative neuroplasticity (4), depending on lifestyle habits, gives us a certain capacity to decide at a personal level how we want the passage of time to affect our brain. Based on this, a hypothesis that fits with this idea of neuroplasticity is the “use it or lose it” (5), referring to the fact that what is not used ends up deteriorating, or in brain terms, what is not stimulated stops being efficient. Therefore, one of the sources of cognitive reserve may be engaging in activities that represent novelty (and, consequently, are far from automaticity) and have a cognitive component. In this way, by promoting that brain efficiency, the clinical expression of the progression of a neurodegenerative disease could be delayed or, alternatively, a brain injury could be compensated for more efficiently (6).

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Do we have tests in Spain to measure it?

The big problem is usually how to measure this reserve. Research over these decades has allowed us to better understand how that reserve can be generated and, also, what we should pay attention to when trying to quantify it (7,8). In Spain we currently have several Number Lines that can be useful. For example, the Cognitive Reserve Questionnaire (CRQ) (9) consists of 8 items to score that collect information on formal education, parents’ education, occupational history, musical training among others, considering these as “sources” of that cognitive reserve.

On the other hand, we also have the Cognitive Reserve Scale (10) which records the score on a series of activities both during youth and during adulthood (and in another version, older age) of aspects related to education, hobbies or the social area.

Lastly, recently validated in an older population, we have the questionnaire of a cognitively stimulating activities (11) that records 10 activities that can be considered as generators of that cognitive reserve or, at least, seem Relating with other Peoplecon a better state of cognitive functioning in older adults.

Along this line, it is very likely that in the future we will see more research that clarifies a bit the functioning of this cognitive reserve, and perhaps more importantly, how to learn to use it in the clinical context to assess the progression of people with brain injury and the way to incorporate it into treatment.

References

- Katzman R, Aronson M, Fuld P, Kawas C, Brown T, Morgenstern H, et al. Developmentofdementingillnesses in an 80-year-old volunteercohort. Ann Neurol. April 1989;25(4):317-24.

- Satz P. Brain reserve capacityonsymptomonset after braininjury: A formulation and reviewofevidenceforthresholdtheory. Neuropsychology. 1993;7(3):273-95.

- Stern Y. Whatiscognitive reserve? Theory and researchapplicationofthe reserve concept. J IntNeuropsycholSoc JINS. March 2002;8(3):448-60.

- Vance DE, Wright MA. Positive and negativeneuroplasticity: implicationsforage-relatedcognitive declines. J GerontolNurs. June 2009;35(6):11-7; quiz 18-9.

- Hultsch DF, Hertzog C, Small BJ, Dixon RA. Use itor lose it: engagedlifestyle as a buffer ofcognitive decline in aging?PsycholAging. June 1999;14(2):245-63.

- Scarmeas N, Stern Y. Cognitive reserve and lifestyle. J Clin ExpNeuropsychol. August 2003;25(5):625-33.

- Schinka JA, McBride A, Vanderploeg RD, Tennyson K, Borenstein AR, Mortimer JA. Florida CognitiveActivitiesScale: initialdevelopment and validation. J IntNeuropsycholSoc JINS. January 2005;11(1):108-16.

- Salthouse TA, Berish DE, Miles JD. The role ofcognitivestimulationontherelationsbetweenage and cognitivefunctioning. PsycholAging. December 2002;17(4):548-57.

- Rami L, Valls-Pedret C, Bartrés-Faz D, Caprile C, Solé-Padullés C, Castellví M, et al. Cuestionario de reserva cognitiva. Valores obtenidos en población anciana sana y con enfermedad de Alzheimer. Rev Neurol. 2011;52(4):195-201.

- León I, García-García J, Roldán-Tapia L. EstimatingCognitive Reserve in HealthyAdultsUsingtheCognitive Reserve Scale. PLOS ONE. July 22, 2014;9(7):e102632.

- Morales Ortiz M, Fernández A. AssessmentofCognitivelyStimulatingActivity in a SpanishPopulation. Assessment. May 1, 2018;1073191118774620.

If you liked this post about cognitive reserve, you might be interested in these NeuronUP articles.

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Reserva cognitiva: ¿De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de ella?

Instructions in Cognitive Rehabilitation: Methods, Design, and Efficacy

Instructions in Cognitive Rehabilitation: Methods, Design, and Efficacy

Leave a Reply