We present 12 neurorehabilitation activitieseffective for treating neurological diseases.

What is neurorehabilitation?

Neurorehabilitation consists of a set of well-designed and planned activities and strategies that aim to recover, compensate for or slow down the deterioration of certain functions affected after brain damage.

After any brain injury or alteration, significant changes occur in life. There are changes in cognitive functioning, in emotions and also at a physical level, such as muscle tone or movements.

However, neurorehabilitation or neuropsychological rehabilitation can be developed to improve different areas of the individual. The cognitive domain is trained (attention, memory, orientation…), physical aspects such as activities that work fine hand movements and even the emotional world of the person.

Let us not forget that the goal is both to restore functional capacities and to help the affected person and their family cope with the new situation.

What is the goal of neurorehabilitation?

The main goal of neurorehabilitation is to relearn skills that are at risk due to any type of brain injury or to develop the patient’s maximum potential, ensuring they can lead a life of maximum independence and satisfaction.

Thus, tasks and exercises that are fully personalized are repeated. For this, a thorough patient assessment is first carried out, discovering their strengths and the things that interest and motivate them, since we will use this to reduce their deficits.

This involves great work, as it is necessary to know the patient well to design activities that really address their difficulties and correspond to their real environment: activities that facilitate that they can walk alone again, swim again or carry out their gardening tasks.

What do we do when it is not possible to recover a function?

Through neurorehabilitation activities not only is the lost ability trained directly, but the intact abilities are enhanced.

In other cases, the goal may be for the patient to learn to use external cues or devices to minimize their limitations. Here the use of emerging new technologies is very useful (Sanz Cortés y Olivares Crespo, 2013): applications that respond to various needs, send reminders, alarms, text-to-speech devices, etc.

Is brain training effective?

If it is designed by a professional based on scientific evidence and adapted to the person’s real needs, yes.

We know that neurorehabilitation is effective because it is proven that our brain is plastic, that is, when we carry out neurorehabilitation activities repeatedly, our neural connections reorganize. Thus, multiple new synapses are created and are strengthened over time.

For example, if you are learning something from this text and you remember it tomorrow or in a few days, it is because your brain has established new connections. Thus, the brain is in continuous change depending on how we train it.

However, plasticity has certain limits and its magnitude depends on age or the injury, but it is never lost.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

12 neurorehabilitation activities

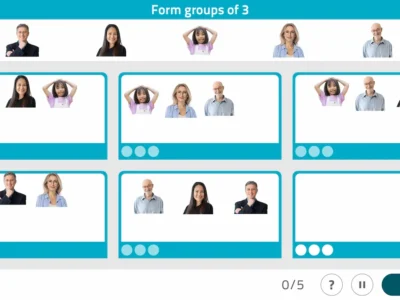

First of all, you should know that one activity usually trains several abilities simultaneously. In fact, it is almost impossible to work on attention, memory or executive functions in isolation.

Neurorehabilitation depends heavily on the existing deficits and the person’s diagnosis. However, the most commonly used activities are included here, since it is frequent to have alterations in attention and/or memory.

You should know that there are many variants and that the same function can be trained in multiple ways and formats.

For example, NeuronUP has a wide variety of computerized activities that work on more than 40 patient areas.

If you want an idea of what neurorehabilitation activities are like, here are the best known ones, although the variations are endless:

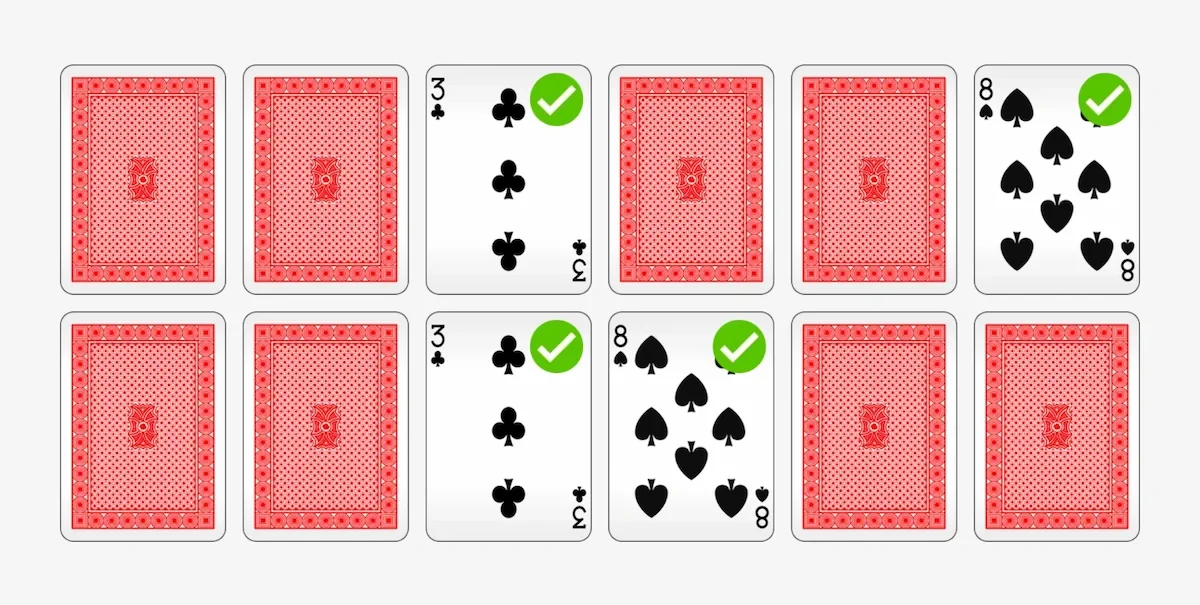

1. Matching the Cards

What does it involve?

An example is the card matching activity from NeuronUP.

What does this activity train?

It trains attention, perception and short-term memory.

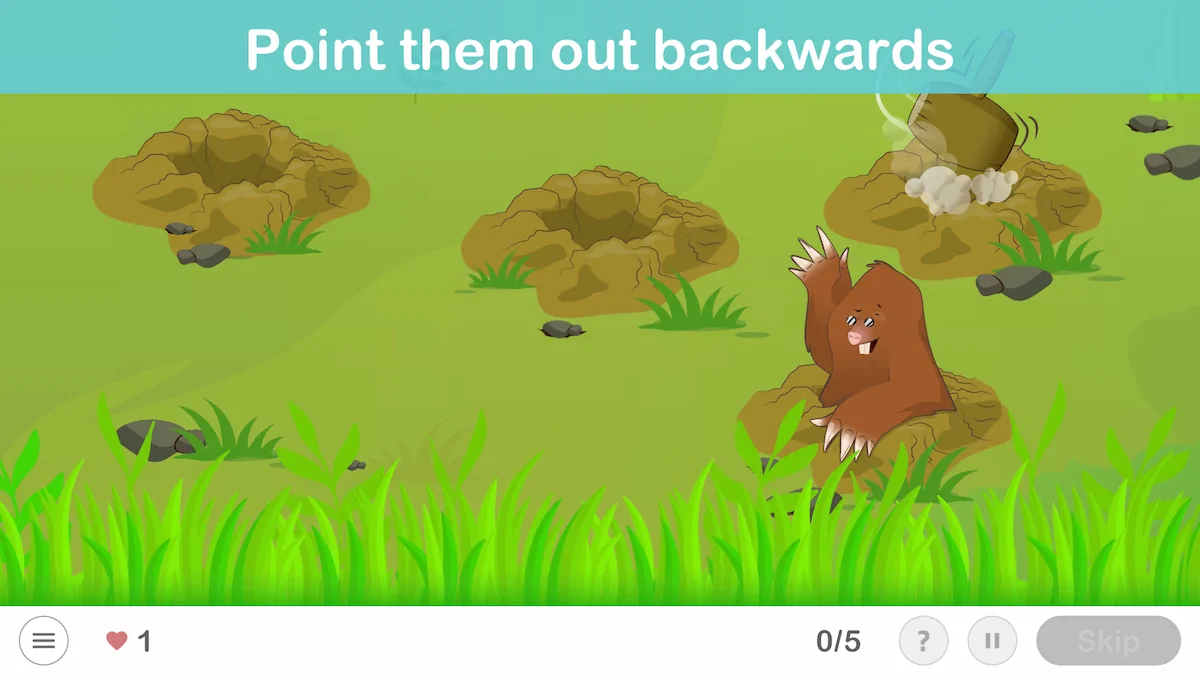

2. Mole invasion or repeat a marked order

What does it involve?

The patient must first remember the order in which the moles appear and then reproduce it, but in reverse.

What does this activity train?

It trains sustained attention and short-term memory in Mole invasion.

3. Tap on objects that appear suddenly

The patient must stay focused on the screen, as sudden and unpredictable stimuli will appear and they must tap them as soon as they perceive them.

It is an activity that trains both processing speed and focused or sustained attention, which means maintaining attention on the same task for a prolonged time.

4. Give a response when hearing the key stimulus

Something similar that also trains sustained attention would be to present a series of sounds auditorily, with the goal of hitting the table when they hear the target number, word or sound.

5. Sorting Bugs

An example to work on sustained attention in NeuronUP is the activity Sorting Bugs, very useful in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

What does it involve?

The objective is to let the beetles pass to one side and keep the ladybugs on the other side.

What does this activity train?

Attention must be continuously focused on the movements of the insects as they approach the wall, to move the door up or down.

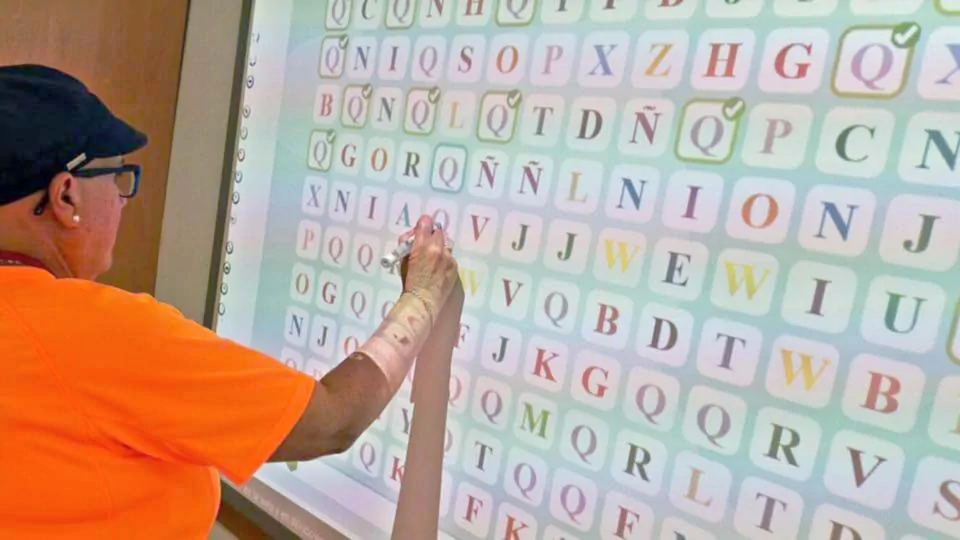

6. Hide-and-Seek with Letters

What does it involve?

A widely used activity consists of a grid full of elements that can be different figures, numbers or letters. The goal is to point to or cross out a certain figure, number or letter.

NeuronUP offers this task, among many others. As we can see, one must select a key letter within a group of letters (in this case the letter “Q”):

What does this activity train?

It is used to train selective attention, which is the ability to focus on something specific while ignoring other stimuli.

Selective attention can also be trained by searching for words in word-search puzzles or locations on a map.

7. Hide-and-Seek with Letters changing the target every so often

If we transform the task by changing the element to be crossed out every 15 seconds (depending on the patient), we would be working on alternating attention. It is the ability to shift our focus of attention from one task to another.

8. Tapping

What does it involve?

It consists of tapping successively with a finger on a surface while performing another task, such as reading a text.

What does this activity train?

This activity is perfect for training dual execution. For example when we drive and talk at the same time, we consider that attention is placed on a single task (talking), and driving is performed automatically. For example, novice drivers do not talk, at most they alternate attention between driving and conversation.

9. Questions about your life, using photos or personal objects

What does it involve?

Very common in Alzheimer’s, it involves asking patients questions such as “Where did you study?”, “How was your wedding day?”, “Who are your siblings?”, etc. Or using objects or old photographs and asking them to express their memories.

What does this activity train?

It helps improve autobiographical memory, which refers to personal events from the past. The activities will depend on each person’s life and training it requires reliable information about the patients’ past.

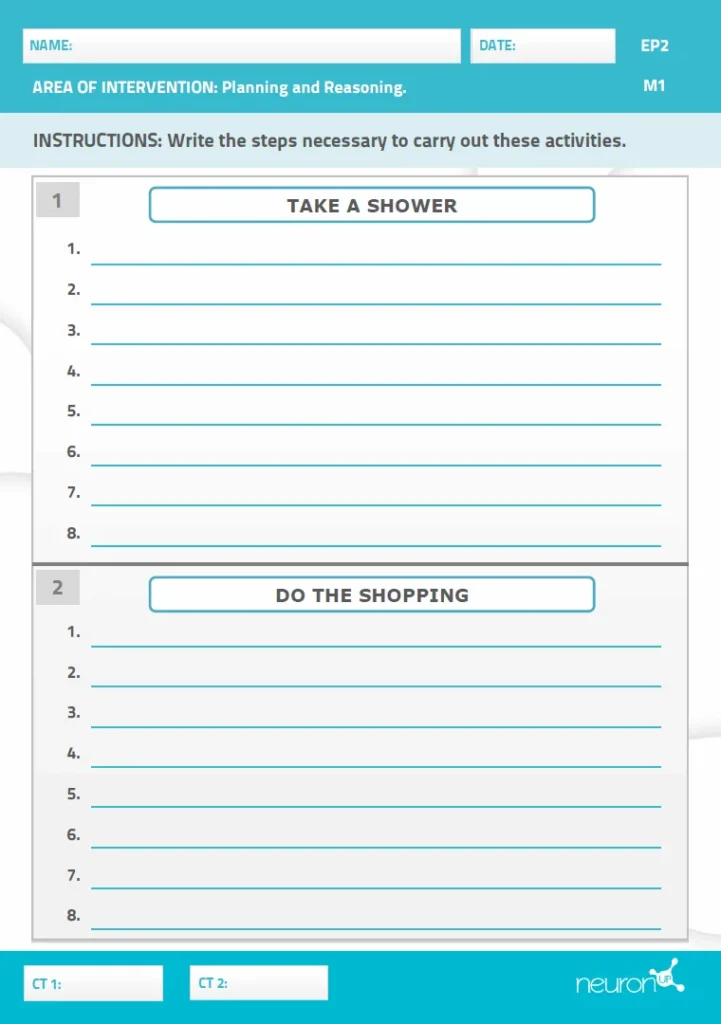

10. Order the steps of activities

What does it involve?

Nondeclarative or procedural memory is the one that involves movements and actions we have learned and perform automatically. Like writing, riding a bicycle, playing an instrument, cooking a certain dish, etc.

Procedural memory is something automatic, very difficult to explain if you want to make it conscious. We ride a bicycle without knowing how we do it. Procedural memory would be worked on by performing the action itself and achieving automatization.

A preliminary task to achieve procedural memory can be to ask patients to tell you all the steps they would follow to make a recipe, take a shower or perform a household task.

Objects can also be used to practice old skills such as knitting, sewing on a button, screwing something, tying knots in a rope, playing a tambourine, etc. Or even with the body itself: whistling, snapping fingers, making a certain gesture, imitating a sound…

What does this activity train?

At the same time some of these tasks can improve praxis and executive functions.

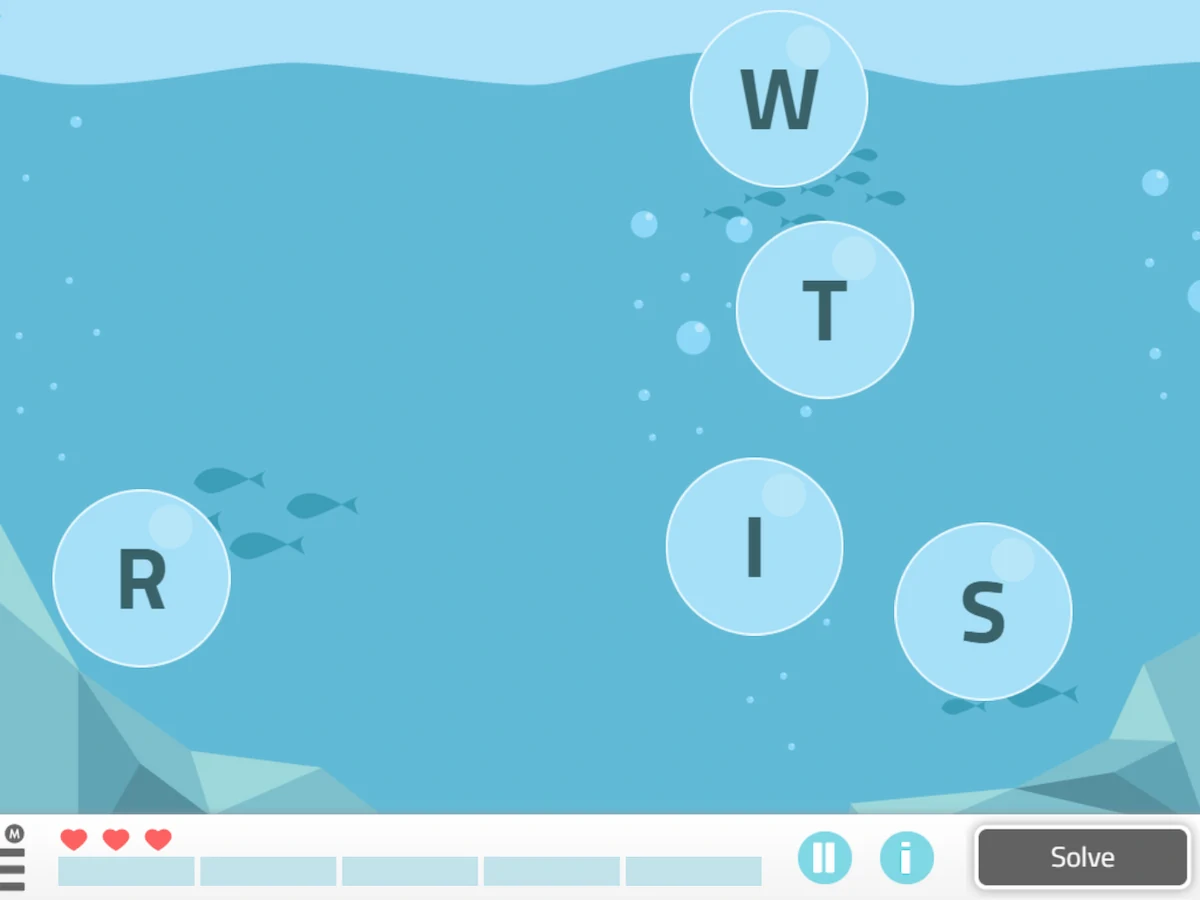

11. Making Words

What does it involve?

As we can see in the image, the patient must select each letter in the corresponding order to build the word.

What does this activity train?

It is useful for language and semantic memory, which stores general knowledge and concepts we have learned during our lives. It also trains working memory (mentally testing different combinations until finding the word).

Other ways to use it

It can also be worked on with activities such as:

- Explain to us what a word means.

- Present a series of sentences about definitions, having the person say which is true and which is false.

- Describe to us what certain objects are used for.

- Name things we can find in a certain environment (such as a pharmacy).

Tasks involving synonymous and antonym concepts, questions about famous people or well-known places, recalling popular sayings, etc., are also useful.

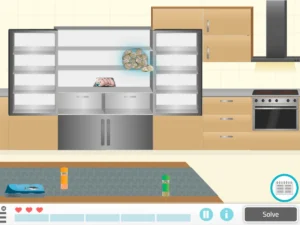

12. Straighten Up the Kitchen

What does it involve?

NeuronUP offers an activities of daily living task called Straighten Up the Kitchen which consists of placing the kitchen objects in their corresponding place.

What does this activity train?

The patient can train several cognitive areas with different degrees of difficulty. As the main function, reasoning and, secondarily:

- Sustained attention,

- semantic memory,

- episodic memory,

- cooking,

- Cleaning

Activities of daily living are those activities that increase a person’s independence and adaptation to the environment. For example, buttoning buttons, shopping, combing hair, etc.

Neurorehabilitation can also focus on areas such as processing speed, visuospatial skills, social cognition, flexibility, etc. As we said, in this world as complex as the mind, the possibilities are endless!

References

- New Zealand Guidelines Group (NZGG). (2006). Traumatic Brain Injury: Diagnosis, Acute Management and Rehabilitation. Evidence-based best practice guideline. Retrieved from: http://www.neuro-reha.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/guideline_tbi.pdf

- Cortés, Ana Sanz, and María Eugenia Olivares Crespo. (2013). REHABILITACIÓN NEUROPSICOLÓGICA EN PACIENTES CON TUMORES CEREBRALES. Psicooncología 9, 2/3: 317-337.

- Estévez-González A., García-Sánchez C., Junqué C. (1997). La atención: una compleja función cerebral. REV. NEUROL.; 25 (148): 1989-1997.

- García Sevilla, J. (2010). Estimulación cognitiva de la memoria. Retrieved on September 27, 2016, from University of Murcia: http://ocw.um.es/cc.-de-la-salud/estimulacion-cognitiva/material-de-clase-1/tema-6-texto.pdf

Article written by Lifeder, online magazine of Psychology, personal development, self-improvement and motivation: http://www.lifeder.com/

If you liked this article about 12 Neurorehabilitation Activities for neurological diseases, you might also be interested in:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

12 Actividades de neurorrehabilitación efectivas para tratar enfermedades neurológicas

Dyslexia: what it is, symptoms, types, and exercises for people with dyslexia

Dyslexia: what it is, symptoms, types, and exercises for people with dyslexia

Leave a Reply