On the occasion of World Hearing Day, in this article we address the relationship between hearing and the brain, paying special attention to how hearing loss affects cognitive functions and the hearing rehabilitation strategies that can be adopted.

Introduction

Every March 3 is World Hearing Day, an initiative promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO) to raise awareness about the importance of hearing health and the prevention of hearing disorders (World Health Organization, 2023). In the field of neurorehabilitation, hearing plays a crucial role in cognitive processing, communication and quality of life.

Recent studies have shown that hearing loss not only affects sound perception, but can also negatively impact memory, attention and other key cognitive functions (Lin et al., 2013).

This article explores the connection between hearing and the brain, the effects of hearing loss on brain function and hearing rehabilitation strategies within the scope of cognitive stimulation.

The connection between hearing and the brain

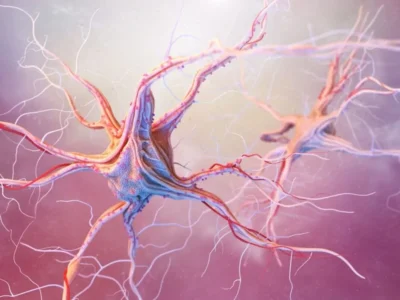

The human auditory system is a complex neurosensory process that not only involves the ears, but also other brain structures essential for the perception of sounds and communication (Peelle et al., 2010).

When the ear captures a sound, sound waves are transformed into electrical impulses that travel through the auditory nerve to the auditory cortex, located in the temporal lobe of the brain. This area is key to interpreting the meaning of sounds, recognizing voices and understanding language.

This process involves key structures such as:

- Outer, middle and inner ear, responsible for capturing and transmitting sound waves.

- Auditory nerve, which carries the information to the brain.

- Auditory cortex, located in the temporal lobe, where sounds are processed and interpreted.

Moreover, hearing is closely related to other cognitive functions. Studies have shown that untreated hearing loss can accelerate cognitive decline and increase the risk of dementia (Livingston et al., 2020). This may be due to the cognitive load involved in compensating for hearing loss, as well as reduced brain stimulation and decreased social interaction (Oxford University, 2021).

When this system is disrupted by hearing loss, the brain needs to compensate for the deficit by reallocating resources to interpret sound less efficiently. Research suggests that this additional effort can generate cognitive overload and lead to impairment in other brain functions (Lin et al., 2013).

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

Impact of hearing loss on cognitive function

Hearing loss not only affects the ability to hear, but also has a significant impact on cognitive function. When the brain receives fewer auditory stimuli, processing capacity and related brain functions, such as memory and attention, can be affected (Arlinger, 2003). Lack of auditory stimulation reduces the activation of certain brain areas, which can lead to a decrease in cognitive efficiency.

Various studies and scientific research have shown a correlation between hearing loss and cognitive decline, especially in older adults (Livingston et al., 2020).

Various theories have been proposed about this correlation, such as, for example, avoiding social interactions. However, this can trigger social isolation which, together with the additional cognitive load of trying to understand sounds, would generate mental stress that could accelerate cognitive decline (Oxford University, 2023).

Strategies for hearing rehabilitation

Hearing rehabilitation goes beyond restoring the ability to hear; it also involves mitigating the negative effects of hearing loss on cognition and strengthening the connection between hearing and the brain.

To achieve this, it is essential to implement strategies that promote brain stimulation and improve communication. Some of the most effective include the use of hearing devices, specialized hearing rehabilitation therapies and targeted cognitive stimulation, as well as adopting healthy habits that enhance sound processing.

1. Use of hearing devices for hearing rehabilitation

Hearing devices play a key role in hearing rehabilitation, since they not only improve the ability to hear, but also stimulate the brain, helping to prevent the cognitive decline associated with hearing loss (Lin et al., 2013).

Technology has advanced significantly in this field, offering personalized solutions for each type of hearing loss.

The use of hearing aids or cochlear implants helps stimulate the auditory system, improve sound perception, prevent sound deprivation and, ultimately, reduce the brain’s cognitive load.

Using hearing devices not only helps compensate for hearing loss, but also strengthens the connection between hearing and the brain, improving quality of life and preventing social isolation.

Various studies support the idea that protecting hearing by using hearing protection in noisy environments or adopting hearing aids can prevent or reduce the risk of dementia. However, it should be borne in mind that the adaptation process to these devices requires time and training to optimize their effectiveness.

What hearing devices can be used for hearing rehabilitation?

1. Use of hearing aids for cognitive rehabilitation

Hearing aids amplify sounds and improve speech perception, facilitating communication in different environments. There are digital models that automatically adapt to volume changes and reduce background noise, allowing a clearer and more natural listening experience.

2. Use of cochlear implants for hearing rehabilitation

For people with severe or profound hearing loss, cochlear implants are an effective alternative. These devices transform sound into electrical signals that directly stimulate the auditory nerve, restoring auditory perception even in cases where hearing aids are not sufficient.

2. Cognitive stimulation therapies for hearing rehabilitation

On the other hand, the hearing rehabilitation not only depends on the use of hearing devices such as hearing aids or cochlear implants, but also requires a comprehensive approach in which cognitive stimulation plays a key role.

The cognitive stimulation therapies help strengthen key functions such as auditory memory, selective attention and auditory processing speed, optimizing the ability to understand speech, especially in challenging environments (Peelle et al., 2010).

In this sense, cognitive stimulation sessions focused on reading aloud, active music listening and performing auditory memory games promote the integration of sound with other cognitive functions, improving attention and verbal comprehension, in addition to fostering the neural connections responsible for auditory processing.

Among the techniques used the following stand out:

- Auditory discrimination exercises, aimed at training the brain to differentiate similar sounds, facilitating speech comprehension.

- Memory activities, focused on reinforcing the ability to remember and process auditory information.

- Selective attention games, designed to help concentrate on specific sounds in noisy environments.

- Phonological processing exercises, aimed at improving the identification and production of speech sounds.

- Sound lateralization and/or localization activities, which help orient where each sound is coming from.

3. Promotion of healthy habits

Prevention and care of the auditory system are fundamental to prevent the progression of hearing loss and optimize rehabilitation outcomes (World Health Organization, 2023).

Below are some tips focused on maintaining good hearing and cognitive health:

- Avoid prolonged exposure to loud noises that can accelerate hearing loss. Moderating the volume on electronic devices can also reduce the risk of hearing damage.

- Maintain a balanced diet, rich in antioxidants and fatty acids such as omega-3, magnesium and vitamins A, C and E, which promote the health of the inner ear.

- Engage in regular physical exercise, to improve blood flow in the inner ear and reduce the risk of age-related hearing loss.

- Avoid smoking and excessive alcohol consumption, as both factors are associated with an increased risk of hearing impairment.

- Have regular hearing check-ups, to allow early detection of hearing problems and facilitate appropriate intervention.

Conclusion

The relationship between hearing and the brain is a field of growing interest within neurorehabilitation. Hearing loss not only affects sound perception, but can also have consequences for memory, attention and cognitive function in general.

Early detection, the use of hearing devices, cognitive stimulation therapies and the implementation of healthy habits are key strategies to mitigate these effects and improve patients’ quality of life.

References

- Arlinger, S. (2003). Negative consequences of uncorrected hearing loss – A review. International Journal of Audiology, 42(sup2), 17-20.

- Lin, F. R., Yaffe, K., Xia, J., et al. (2013). Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(4), 293-299.

- Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., et al. (2020). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 396(10248), 413-446.

- Stevenson, J. S., Clifton, L., Kuźma, E., & Littlejohns, T. J. (2022). Speech‐in‐noise hearing impairment is associated with an increased risk of incident dementia in 82,039 UK Biobank participants. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 18(3), 445-456.

- Stevenson, J., & Littlejohns, T. (2021, 21 de julio). Difficulty hearing speech could be a risk factor for dementia. University of Oxford. https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2021-07-21-difficulty-hearing-speech-could-be-risk-factor-dementia

- Peelle, J. E., Troiani, V., Wingfield, A., & Grossman, M. (2010). Neural processing of speech in aging and hearing loss: Functional MRI evidence of compensatory mechanisms. The Journal of Neuroscience, 30(48), 15250-15258.

- World Health Organization (2023). World Hearing Day: Hearing care for all. Available at: https://www.who.int

If you liked this blog post about the relationship between hearing loss and cognitive functions, you will surely be interested in these NeuronUP articles:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Audición y cerebro: La relación entre la pérdida auditiva y las funciones cognitivas

Leave a Reply