In this article we present the difficulties and possible strategies of the caregiver’s communication toward the patient with dementia.

Communication is a means of verbal and nonverbal expression that allows us to interact with others, being a resource of utmost importance in the relationship between the patient with dementia and their primary caregiver. Usually, faced with uncertainty about how to approach and communicate with people with dementia, caregivers and close relatives often choose to restrict them from social situations and contact with others, thinking that they do not need to interact and integrate into the environment around them.

Due to inefficient communication, caregivers can limit their performance, as well as affect the emotional state of the patient with dementia. Therefore, we need to know the impairments in language that people with dementia may exhibit, so as to develop communication strategies and create an assertive connection between the patient and us. This is because daily we need to communicate with them to identify their needs and interests, and through language we encourage them to cooperate in performing their daily activities. Based on the above, we will address various language impairments that patients with dementia may present, as well as strategies to establish better interaction.

Subscribe

to our

Newsletter

What is dementia?

It is the term that refers to the presence of progressive cognitive decline, which is characterized by impairments in cognitive processes such as: orientation, attention, concentration, short- and long-term memory, as well as behavioral and mood disturbances that limit the autonomy and independence of patients with dementia. Leading them to require individual assistance from specialists such as physical therapists, nurses, geriatricians, cognitive psychologists and family members known as primary caregivers.

Language impairments in patients with dementia

There are various types of dementia; on this occasion we will address Alzheimer’s dementia, vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia.

Alzheimer’s dementia

Patients with Alzheimer’s dementia usually have a slowly progressive course; thus, at the onset of the disease they show impairments that are regularly associated with immediate memory, which makes it difficult for them to consolidate new information. Episodic, semantic and working memory are also affected, in addition to the emergence of behavioral changes, deficits in visuospatial processes and anomias that can directly affect language and communication with the environment.

Vascular dementia

The impairments in vascular dementia can result from a single infarct that damages different cortical regions, triggering serious repercussions in some areas such as: the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, parietal [cortex], temporal neocortex of the transmodal node or Wernicke’s area, to name a few. This is a negative aspect since it could affect language comprehension, also presenting impairments in the retrieval of semantic and episodic memory, to name only some.

Frontotemporal dementia

Regarding frontotemporal dementia, these patients regularly have impairments in grammatical and syntactic fluency, causing them to omit the use of conjunctions and prepositions, using only verbs and nouns in their communication. Interaction with these patients is often severely affected in more advanced stages of the condition, as they tend to become disinhibited to the point of displaying behaviors that are socially unacceptable such as shouting, removing their clothing, swearing, among others, which causes distancing by primary caregivers and social rejection.

Semantic dementia

Finally, the symptoms of semantic dementia resemble some presented in Alzheimer’s dementia, since one of the first impairments is in language. In this particular condition the most harmed process is semantic memory, which affects the retrieval of information linked to content, topics, concepts and facts that have been stored throughout the patient’s life, these impairments being a major hindrance that can restrict their language and verbal expression toward others.

Communicating with the patient with dementia

After having learned about some language and cognitive process impairments that patients with dementia suffer, our role as specialists and primary caregivers is to carry out effective strategies that allow us to communicate optimally and assertively with our family member or patient, thus having the goal of helping them in the daily performance of their activities, contributing to achieving a better quality of life and ultimately developing positive emotional bonds that provide them with calm and, above all, security.

15 strategies to communicate with our family member or patient

Below we share 15 strategies that facilitate communication with people who have dementia.

- Use an appropriate tone of voice according to their hearing needs; consider if the patient has hearing deficits or uses hearing devices. Using soft tones of voice may not be useful for all patients. We must identify the characteristics of our patients and relatives to determine the tone that allows them to hear us clearly.

- Speak clearly and slowly so that the patient or relative can absorb the information being given. Avoid using unusual words or speaking quickly.

- Provide concrete instructions, one instruction at a time, for example: “close the cabinet, open the window, wash the dishes”. Do not overload with complex instructions.

- Maintain eye contact at all times, for example: when giving an instruction, when talking to them or asking something.

- In advanced stages use and encourage the use of gestures to complement communication. For example: “the gesture of brushing one’s teeth, going to sleep, saying yes and no.”

- Make physical contact with the patient, gently press their hand or shoulder while giving an instruction or while speaking to them kindly.

- Call them by their name, or ask how they would like to be called; do not infantilize them with diminutives or incorrect terms such as “old man”, “grandpa”, or “elder”.

- Help them retrieve information, give phonological or semantic cues about how the word or concept they want to say begins. For example: name of a common red fruit (ma) = apple.

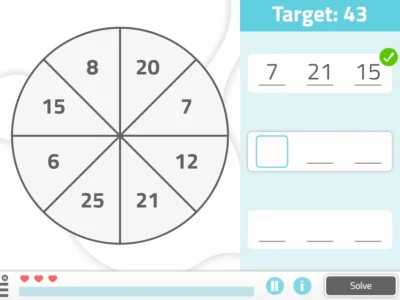

- In advanced stages of dementia use visual support through signs, pictograms, a photo album in physical or digital form.

- Validate the patient’s speech. Do not confront information; encourage them to answer new questions instead of repeatedly telling them they have already talked about the topic several times. Example: they told us three times that they went to the park; instead of confronting them, ask: What did you see at the park? When did you go? How did you feel? What other parks do you know?

- Encourage the patient to write short phrases in a notebook, on a board or on the refrigerator.

- Encourage them to communicate with other people by phone or virtually.

- Make them part of a family conversation, ask them to address a topic they are passionate about, ask them questions about it.

- Make appropriate repetitions, repeat instructions or information that the patient needs.

- Establish roles and quality time with the patient. The primary caregiver also needs rest to be in optimal physical and emotional condition with the patient.

Conclusions

The patient with dementia suffers from diverse language and communication impairments during the progression of the disease. Therefore, our goal as caregivers and specialists is to provide them with tools and strategies that allow them to integrate as much as possible into their social environment and remain in contact with it.

It is a daily challenge that is often difficult but that, with the help of specialists, support networks and information we can overcome the complications that this disease entails. It is extremely important to remember that although they suffer from a neurocognitive disorder, they are human beings who deserve our attention, patience, empathy, care and above all much love.

Bibliography

- Aguilar, V., Martínez, R., Sosa, O. (2016). Differential diagnosis of dementias. National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery. http://repositorio.inger.gob.mx/jspui/handle/20.500.12100/17226

- Nilton, C., Montesinos, R. (2015) Alzheimer’s disease. Getting to know the disease that came to stay.

- Brooker, D., & Surr, C. (2005). Dementia care mapping. Bradford: Bradford Dementia Group.

- Mace, N., & Rabins, P. (1997). When the Day Has 36 Hours. Mexico: Editorial Pax Mexico.

If you liked this post about communication toward the patient with dementia, you might be interested in these NeuronUP articles.

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Comunicación del cuidador hacia el paciente con demencia

Social perception in schizophrenia

Social perception in schizophrenia

Leave a Reply