Neuropsychologist Aarón Fernández explains neuropsychological assessment and neuropsychological rehabilitation in aphasias.

The role of neuropsychology in aphasias

Aphasias, defined as the set of language and communication impairments resulting from brain damage, represent a limitation for the person’s life development that goes far beyond the language problem itself.

Given this complexity, it is necessary to have a team made up of many professionals who, from different perspectives, try to help recover the greatest possible functionality and facilitate the person’s adaptation to their new life situation.

Speech therapists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, social workers, clinical psychologists should provide their assessment, and, if necessary, their intervention options. Of course, the neuropsychologist also plays an important role in this whole process which we will try to outline in this article.

The neuropsychologist is responsible for describing the cognitive profile that the person presents after the brain injury that caused that aphasia. In this sense, when we understand language as a cognitive function, it is difficult to try to separate it from other functions on which it is based and which it also influences, such as working memory, executive function, memory, among others (1). Knowing this profile can be an important key to knowing what we have and what we do not have for rehabilitation.

Moreover, neuropsychology is one of those responsible for channeling the different advances we are having from the neurosciences about the functioning of language itself and that are enabling new ways of approaching rehabilitation, moving from a model of syndromic categories to a model of approach based on language processes (2,3).

Neuropsychological assessment of aphasias

The underlying model

One of the important requirements for the neuropsychological assessment of language is having a model that allows us to understand how it works.

It is common to resort to the classical Wernicke-Geschwind model (4) which proposes a series of closed and segmented syndromes, but which proves insufficient to describe the language impairments present in a person with aphasia, and, therefore, not very specific to be the evaluative basis that would form the basis of a subsequent rehabilitation program.

At two perfectly complementary levels we have some models that may be more useful to us.

At the anatomical-functional level, we have the dual-route model proposed by Hickok and Poeppel (5) which defines two routes related to linguistic production and language comprehension respectively.

A dorsal route (equivalent to the Wernicke-Geschwind model itself) related to aspects of phonological construction, grammar and articulatory control, and a ventral route more related to aspects of auditory comprehension, both the discrimination of verbal sounds, as well as semantic or grammatical aspects.

Subsequently, Friederici and Gierhan (6) added two subdivisions to those routes that attempt to separate several processes and associate them with different fasciculi.

At a more purely cognitive level we have the language processing model proposed by Ellis and Young (7) that allows us to dissociate various processes within the different aspects of language that we have typically assessed, and, therefore, to more clearly discern the cause of the problem we observe. Its knowledge becomes fundamental for a correct approach to aphasias.

Neuropsychological Rehabilitation of Language

Approach to aphasia rehabilitation

Starting from these premises, our neuropsychological approach must be centered on working with the processes that we find altered after our prior assessment.

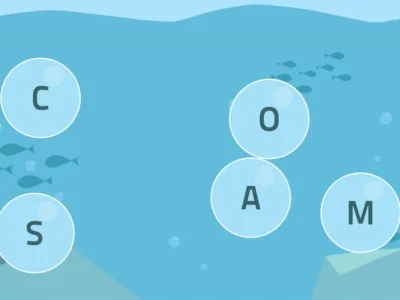

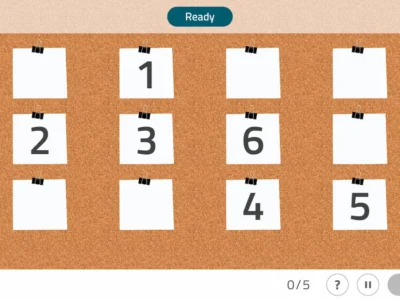

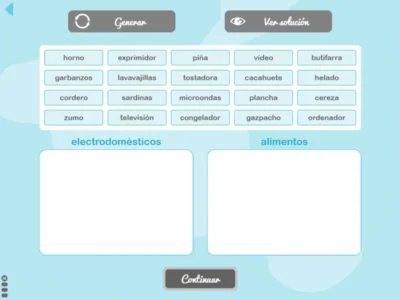

These can be rehabilitated using classical techniques such as the errorless learning or by associating different elements with the linguistic productions (for example, associating elements of a sentence and their order with colors to work on agrammatisms). What is inferred upon reaching this point is that each treatment will be specific and very different for each person.

Still, the REGIA program is noteworthy, which employs the method of constraining the movement of the healthy limb to the language sphere, restricting non-verbal language in this case. It is an intensive and group treatment that has good scientific evidence for its use (9).

Another important key is the use of alternative communication systems, as a variant to compensate for the more severe language difficulties the person presents.

It should not be forgotten that, after an aphasia, the person ends up needing a complete adaptation to their environment and to understand the world in a new way (10), so the intervention should not remain only in our consultation.

In the chronic phase

Finally, it should be stated that neuropsychological treatment in aphasias has been shown to be very effective in the year following the injury, but also when we enter the chronic phase, since there is evidence supporting extending treatment in chronic patients regarding their outcomes (9).

Bibliography

- Cahana-Amitay D, Albert M. RedefiningRecoveryfromAphasia. Oxford, New York: Oxford UniversityPress; 2015. 296 p.

- Tremblay P, Dick AS. Broca and Wernicke are dead, ormovingpasttheclassicmodel of languageneurobiology. BrainLang. November 1, 2016;162:60-71.

- Vega FC. Neuroscience of Language: Neurological Bases and Clinical Implications [Internet]. Madrid: Panamericana; 2011 [accessed March 7, 2018]. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=555469

- Geschwind N. Disconnexionsyndromes in animals and man. I. Brain J Neurol. June 1965;88(2):237-94.

- Hickok G, Poeppel D. Dorsal and ventral streams: a frameworkforunderstandingaspects of thefunctionalanatomy of language. Cognition. June 2004;92(1-2):67-99.

- Friederici AD, Gierhan SM. Thelanguagenetwork. CurrOpinNeurobiol. April 1, 2013;23(2):250-4.

- Ellis AW, Young AW. Human CognitiveNeuropsychology: A TextbookWithReadings. PsychologyPress; 2013. 694 p.

- Terradillos E, López-Higes R. Guide to speech therapy intervention in aphasias. 2016.

- Berthier ML, Green C, Lara JP, Higueras C, Barbancho MA, Dávila G, et al. Memantine and constraint-inducedaphasiatherapy in chronicpoststrokeaphasia. Ann Neurol. May 2009;65(5):577-85.

- Paniagua PJ. The environment as a communication system [Internet]. Logocerebral. 2018 [accessed March 7, 2018]. Available at: http://logocerebral.es/entorno-sistema-comunicacion/

If you liked this post about aphasias, you may be interested in these NeuronUP posts:

“This article has been translated. Link to the original article in Spanish:”

Evaluación y rehabilitación neuropsicológica en las afasias

Celebrities contribute to normalizing mental health issues

Celebrities contribute to normalizing mental health issues

Leave a Reply